The Surrealists staged some of the most outrageous and imaginative art exhibitions of the Twentieth Century: in 1938 Marcel Duchamp hung the ceiling of the International Surrealist Exposition with coal sacks and one gallery, strewn with leaves and moss, contained a pond; for the opening the guests were handed flashlights to illuminate the artworks hung in darkened rooms. Frederick Kiesler’s 1942 designs for Art of This Century (Peggy Guggenheim’s New York gallery) included work displayed on a conveyor belt and a gallery where every two minutes the lights would go on and off on opposing walls. For the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition (New York, 1942) Duchamp used a mile of twine to encase the entire gallery in cobwebs through which visitors had to view the paintings and he hired six children to play ball in the space during the opening.

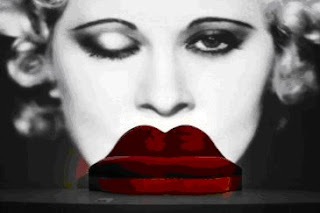

By contrast, museum exhibitions devoted to Surrealism have tended to look institutional, invoking visual and cerebral responses to work that originally assaulted viewers viscerally, erotically and occasionally aurally. The Boijmans van Beuningen had the inspired idea to invite the Antwerp designers, Walter Van Beirendonck and Dirk Van Saene, to create the installation for Surreal Things; Surrealism and Design, organized in partnership with the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao. The result was suitably theatrical and acknowledged the Surrealist’s anarchic displays. Visitors entered through an allee of spinning topiary-like forms made from plastic foliage, cordoned off with chains of wieners cast in metal. At the far end was a wall-sized, winking projection of Mae West; the bright red lips against her black and white image turned out to be the sofa designed by Salvador Dali and Edward James in 1937-38.

Mae West’s Lips Sofa (Edward James and Salvador Dali, 1937-38) in front of a blinking Mae West which greeted visitors at the entrance to Surreal Things at the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam

The main exhibition space was filled with assorted colossal body parts: two arms, a head and one leg (wearing a high-heeled shoe) which functioned as display cases. Van Beirendonck and Van Saene picked up on the Surrealists’ often sadistic approach to the female body (undressed, gagged, bound, and dismembered), while the exhibition itself included work by a fair number of women (Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar, Toyen, Claude Cahun) as well as a very international group of artists including Americans, British, Italians and Swiss. Periodically the galleries were filled with the roar of a jet plane taking off – an updated homage to Kiesler’s use of the sound of trains in Art of This Century.

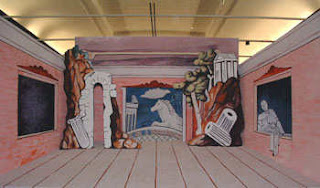

Recreated de Chirico set for the Ballet Russe’s Le Bal

The walls of the main gallery were hung with the Boijmans’ in-depth collection of Surrealist paintings, while the things displayed included both one-off art objects and commercially-produced designs, demonstrating how even the most transgressive art is readily cannabilized in the name of fashion. Some were familiar (Man Ray’s iron embedded with cleat-like nails, Dali’s lobster telephone, Meret Oppenheim’s table with bird’s legs, dresses and accessories by Schiaparelli ), others less-so (textile designs by Miro and Dali, ballet costumes by Miro, Masson and de Chirico, Dali’s designs for Edward James, such as a carpet patterned with paw-prints from a large dog). It also included a number of biomorphic designs with a more questionable debt to Surrealism (Noguchi’s sofa, Charles James’ down evening jacket).

The exhibition included a walk-in model of Frederick Kiesler’s interior for Art of This Century but not even a photo of Kiesler’s major work of Surrealist architecture, the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem (a breast-shaped structure whose interior is the ultimate architectural expression of sexual congress). There was also a re-creation of de Chirico’s set for the Ballet Russe’s Le Bal, and several of his costumes which transformed the dancers into bits of architecture. Dance costumes by Miro and Masson were shown in action in two films which ran in the gallery.

The exhibition was a bit lacking in didactic material that might have justified both its inclusions and exclusions (which the catalogue presumably provided), but more than made up for it with the panache of its installation.

Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870-1936) Nec mergitur (1904-5), oil on canvas, © National Museum in Warsaw. Photo: Piotr Ligier

The National Gallery of Ireland filled in one more piece of the puzzle of fin de siecle art with Paintings from Poland: Symbolism to Modern Art (1880-1939), comprising seventy paintings, largely borrowed from the National Museum in Warsaw. The exhibition’s strength was the Symbolist work; if Symbolism is a movement that no one can define very precisely, there’s little doubt that it was thoroughly international, reaching beyond its best-known manifestation in France to Moscow, Helsinki, and Reykjavík as well as New York and San Francisco.

Apparently Symbolism was significant in Poland, producing such wonderful paintings as Ferdynand Ruszczyc’s Nec mergitur. Ruszczyc’s ghost ship is shown at night, a time beloved by the Symbolists for its emotional evocation of fear, isolation, loneliness, foreboding and horror. The subject of ghost ships is consonant with those emotions, as in the story of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. Another strong night piece was Jozef Pankiewicz’ Nocturne – Swans in the Saxon Garden in Warsaw at Night (1894). The painting was visually renunciatory with its almost total blackness, yet it managed to evoke the heightened sense of smell and sound that take over with nightfall.

Another stand-out was Wojciech Weiss’ Obsession: a frenzy of aroused figures merge into a fire-y red abstract flow which is drawn out of the picture by the undertow of mass hysteria. If the source of their obsession is unspecified, Edward Okun manages to turn the specific subject of war into a generalized nightmare. In We and the War, an old woman crouches behind a young couple; the three of them seem unable to detect the writhing mass of imaginary monsters (with snake-like bodies and insects’ wings) which envelop them. The exhibition also revealed the Symbolist interest in childhood; not the innocence or promise that children hold, but their vulnerability and the fleetingness of youth.

Edward Okun (1872-1945) We and the War (1917-23) oil on canvas, © National Museum in Warsaw. Photo: Piotr Ligier

The later work in the exhibition showed Polish artists assimilating various modernist movements: Strzeminski worked through analytic cubism, Stazewski studied Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism, Hiller responded to Kandinsky’s Paris style; it also revealed an interest in folk art which dates from the later nineteenth century in Central and Eastern Europe.

The exhibition was a welcome opportunity to overcome the isolation which the Cold War imposed on Polish art.