The Evolution of Quilting and/in Museums

Gee’s Bend is a small and isolated African American community in Alabama most of whose population is descended from slaves who worked the local plantation. The women of Gee’s Bend developed a repertory of quilting designs that may reflect the tradition of African textiles but has evolved into a recognizable local style; quilts from Gee’s Bend burst into the museum world in 2002 when the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFA Houston) organized an exhibition of their work that toured twelve museums around the country. I saw it at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC and was struck by two things: the quilts looked like none I had ever seen, and this was the first time within my memory that anything considered either decorative arts or crafts was shown in a major Whitney exhibition.

Decorative arts (and crafts) patterns are often characterized by repeating motifs and designs tend to be symmetrical, as are most traditional American quilts. Those of Gee’s Bend employed large fields of solid colors with distinctly asymmetrical patterns. Hung on the Whitney’s walls they were easily read as abstract art of the sort that Whitney patrons are used to; and I suspect that is how they got their foot in the door. But however mis-read, the quilts were stunning.

Mary Lee Bendolph Work-clothes Quilt (2002) denim and cotton, 72 x 86 in., the Tinwood Alliance

Six years later the MFA Houston has organized another exhibition, Gee’s Bend; the architecture of the quilt, that emphasizes work done since 2002; it’s on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through December 14, 2008. The current exhibition not only challenges the cannons of fine arts museums which rarely devote much attention to vernacular art, but also traces an evolution of style in Gee’s Bend, now that its quilters have had more exposure to quilting elsewhere. And what it reveals is that a more cosmopolitan style is also a more conventional one. Log Cabin, bricklayer, housetop and half square patterns that were hinted at in the earlier work are now fully expressed as regularly repeated units, and symmetry has become the rule for many of the younger quilters. But beyond the pleasure of seeing the quilts themselves, the opportunity to see a style evolve in more or less real time makes for a fascinating exhibition.

I made it a point to attend the opening because ten of the quilters were there and available for conversation; they were a thoroughly charming and gracious company. I spoke with Ruth Kennedy and Mary Lee Bendolph , born in 1926 and 1935 respectively; both described creating their designs in their heads. Mary Lee said that it was only when she saw her work on the walls of the museum in 2002 that she knew she was doing artwork.

Linda Day Clark photo of Mary Lee Bendolph at work in her home, © Linda Day Clark

Loretta P. Bennett and Louisiana P. Bendolph (daughter-in-law of Mary Lee, who instructed her) were younger women who had consciously retained distinctive aspects of the Gee’s Bend style. Both the younger quilters sketch their designs ahead of time. Louisiana said she often drew on paper napkins, so they haven’t survived; when she puts together a design that she thinks unsuccessful she cuts it up and incorporates it into another quilt. Loretta P.Bennett’s story reflects much the broader horizons available to the younger generation; married to a career soldier, she has lived in more than one city in Germany (where she learned German and used her high school French) as well as in various regions of the States. She is very conscious of the unusual and asymmetric designs characteristic of Gee’s Bend; she showed me borders on many of her quilts and pointed out that even they were interrupted and asymmetric.

At the PMA the quilts are preceded by a corridor with photographs that Linda Day Clark took in Gee’s Bend which document the architecture and people of the community. The exhibition itself is arranged according to several categories: housetop and bricklayer patterns, local variations on traditional patterns, quilts made from used work clothes, corduroy quilts made from remnants of pillows that Sears Roebuck had commissioned, and the mother and daughter-in-law relationship of Mary Lee and Louisiana Bendolph. The exhibition is accompanied by a fascinating catalog (that I haven’t yet gotten through, but intend to) with many essays by curators and scholars and, more unusually, three by the quilters themselves. In addition to the related exhibition of Linda Day Clark’s photographs the museum is exhibiting a recent gift of African American quilts: the Ella King Torrey Collection, at the Perelman Building.

The PMA is hosting a day-long symposium on Alternate American Art Worlds on Nov. 15 that will explore the expanding view of art reflected in the museum’s hosting the Gee’s Bend quilts as well as exhibitions by two self-taught artists: Thomas Chambers and James Castle. And on Oct.9th the Arden Theatre is presenting a play set in the area, Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder’s Gee’s Bend.

Cecelia Condit, still from Why not a sparrow? (2002-25)

Modern Fairy Tales

The first New York solo exhibition by Cecelia Condit, curated by video artist Mary Lucier, is on view at Cue Art Foundation, New York City, through Oct. 11. The artist, whose work has been shown internationally, trained in Philadelphia (PAFA, Philadelphia College of Art and Tyler) and lives in Milwaukee where she teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her videos are modern fairy-tales for grown-up women; and like the stories collected by the brothers Grimm, they involve danger, violence, and death. In Oh, Rapunzel we see the adult woman caught between memories of childhood and the present reality of her ageing mother. And this a major theme of Condit’s which was left out of the tales she heard in childhood: not death, but ageing. Condit recounts the ageing mother with her tender, wrinkled skin and diminishing faculties and the ageing daughter confronting changes in both her mother and herself.

Condit’s video’s are shot in luscious colors that recall the paintings of John Millais (he of the floating Ophelia). They have a quality both of unreality and fractured time that makes them seem dream-like. Dreams allow for subjects such as murder and revenge as well as the unlikely soul-mate that a young girl finds in a dead rat, and the artist’s tales allow her audience plenty of room for their own memories and imagination. Condit has been described as the most serious practitioner of the grotesque in video art (Laura Kipnis as quoted by Kerrie Welsh in the small catalog to the exhibition); she describes her own work as exploring the dark side of female subjectivity. This is a haunting, disturbing and beautiful exhibition.

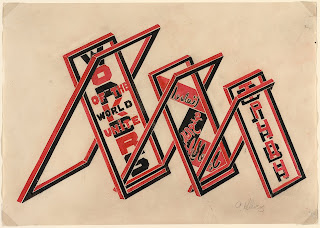

Gustav Klutsis Propaganda Stand (Workers of the World Unite) (1922) gouache over graphite, National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2005

Constructivism at the National Gallery of Art

In Washington last week I wandered into an exhibition of recent acquisitions in the print and drawings department of the National Gallery of Art. I only got through the twentieth-century selection (the exhibition spans medieval to contemporary) but saw some rare gems. Among a group of early Soviet works were two by Gustav Klutsis illustrating stands made to hold political posters; they were so clear that I imagine the designs could be realized.

Kurt Schwitters,Merz 3 (0/5), (1923) color lithograph with collage (artist’s proof), National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006

But what really caught my eye, occupying the wall at the end of three interconnecting rooms, was a portfolio of six lithographs with collage by Kurt Schwitters. I’d never seen them before, which made sense when I read the label: they belonged to the artist and were the only complete set extant. Done when under the influence of Constructivist art, the works were surprisingly elegant and included unexpected imagery such as two cats (above) and other figures that appeared to come from children’s books, and various small silhouettes that might have been appropriated from playing cards. Schwitters produced a small edition of the lithographs, then five sets of proofs to which he added pieces of colored papers. Up through November 2, 2008, they’re worth the trip to D.C..