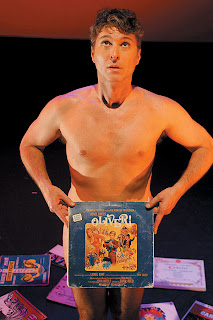

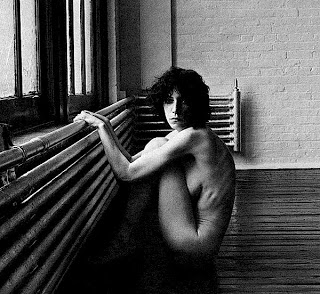

Robert Mapplethorpe Self-Portrait © Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

In the late 80s and 90s the political far right had the most sophisticated appreciation of the power of art in the U.S. and harnessed it to build what would come to be known as the Moral Majority. The power they employed was fueled by fear; fear of difference, of the unknown, of people who were not like them. The far right understood the power of art to embody and personify those differences. They fired the initial shots of what would come to be known as the Culture Wars and twenty years later we are still living in its aftermath.

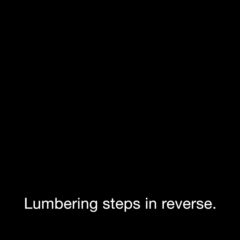

Robert Mapplethorpe from the X Portfolio (1978) © Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

Imperfect Moments: Mapplethorpe and Censorship 20 Years Later, a symposium on Feb. 12-13 co-presented by the Institute of Contemporary Art at Penn (ICA) and the Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative at the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage commemorated those beginnings. The ICA was in the avant garde of the wars; it organized Robert Mapplethorpe: the Perfect Moment which, along with the work of Andres Serano, was subject to the initial attacks in 1989 by U.S. Senator Jesse Helms on the basis of National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) funding. [Note: the Mapplethorpe exhibition was presented in Philadelphia and Chicago, without incident. It’s third stop was supposed to be the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C. which backed out at the last minute. The exhibition went on to Cincinnati where the Contemporary Art Center and its director were indicted for obscenity. Serrano received federal funding to present his work, but the photographs already existed and were not created with federal money] The symposium, held at halls on Penn’s campus, attracted sold-out crowds (and then some) of students and the art community, including many culture war veterans. As Robert Storr, Dean of Yale’s School of Fine Arts who moderated the Friday afternoon session said, memorial commemorations are occasions not only for looking back but for looking forward. What have we learned about cultural conflict, censorship, public funding and the place of art in a democratic society?

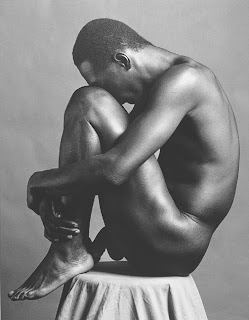

Robert Mapplethorpe Ajitto (1981) © Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

The most powerful aspect of the symposium was that so many of the participants had been in the front lines of the conflict. The first speaker was Janet Kardon who, as director of the ICA, had organized the Mapplethorpe exhibition (the artist had died shortly before it opened). She recounted in detail what it meant to testify on behalf of Mapplethorpe’s work at an obscenity trial in Cincinnati and the difficulty of defending art in the context of the courtroom. The next speaker was Judith Tannenbaum who, as acting director of the ICA during the controversy, became the public face of the institution. She was grateful for the security of being part of a large university which unequivocally defended the academic freedom of its museum as it would any other part of the university. The ICA, however, was subjected to various threats to ban it from receiving federal funding in the future.

Perhaps the most moving talk of the event was given by David Joselit, Professor of Art History at Yale who 20 years ago had contributed an essay to the Mapplethorpe exhibition catalog. Joselit analyzed the basis on which art professionals had defended Mapplethorpe’s work against legal charges of obscenity, although in the end it was their professional authority rather than their arguments which swayed the jury. They used what he called the beauty defense, claiming the photographs as art on formal and aesthetic grounds. Joselit thought this played into the hands of the far right, revealing the powerlessness of aesthetics in the face of art of such powerful affect as Mapplethorpe’s.

Cover for Artforum magazine, September 1979 showing the projection of Mapplethorpe’s works on the facade of the Corcoran Gallery of Art as protest against the cancellation of the exhibition, The Perfect Moment. © Artforum, New York .

The beauty defense demonized the work’s content which it redeemed through its beauty; Mapplethorpe’s work was not only about beauty but was significantly about representing gay male pleasure at a time when it was mostly closeted. The culture wars, he said, succeeded in applying the legal standards of obscenity: does it violate community standards? They reverted to a Khantian notion of beauty that was both universal and disinterested whereas multi-culturalism was making the counter-claim that aesthetics are particular, bound by culture, education, gender and sexuality and highly interested, in that aesthetics are used in signaling and confirming power. Joselit referred to Baudelaire who posited modern art as a ratio between the particular time and place and the universal; democracies are inherently plural and in a democracy, Joselit affirmed, it is crucial that there be room for minority as well as majority communities. This was the significance of Mapplethorpe’s work, and the reason such work must be supported as part of a vital democracy.

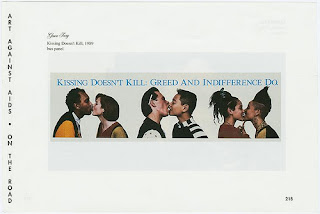

Act Up’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill ad, posted on NYC busses in 1989.

Michael Brenson recounted the pressure of being art critic of the New York Times, the paper of record, during the period and raised the question of how we might define success. He recalled 1989 as the year when Serra’s Tilted Arc was dismantled, pitting the art world against unhappy occupants of a federal office building; Magiciens de la Terre opened in Paris, challenging the art world’s ideas of quality; Act-up’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill ads appeared on NYC busses, bringing aids activism to the broad public; soldiers fired upon students in Teineman Square; the Corcoran canceled the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition and the Berlin Wall came down. Brenson said it was impossible for him to view the artworks apart from the context of the culture wars and struggled to write criticism that incorporated disjunctions. He also struggled with a not-always supportive newspaper.

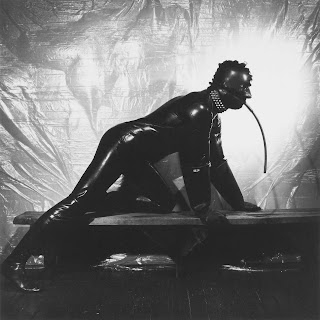

Ron Athey in performance.

Kathy Halbreich told of a battle in 1995 when, as director of Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, she spent an entire six months dealing with what became a national affair over the museum’s sponsorship of Ron Athey, a performance artist who incorporates gay S/M content in his work. The controversy was sparked by a response from a supposed audience member (despite an explicit description of his work in Walker’s brochure), followed by an article in the local newspaper which ultimately led to objection over federal funding used for the event. Halbreich said that the only colleagues who came to her side were a handful who were already close friends. Robert Storr confirmed that such lack of unity by the art world was unfortunately common and recalled that when the Corcoran Gallery of Art canceled the Mapplethorpe exhibition, claiming it didn’t want to upset the forthcoming Congressional hearings on NEA appropriations, neither of the two other museums in the D.C. area who owned Mapplethorpe’s work spoke up in its defense.

Andres Serrano Piss Christ © Andres Serrano.

And then there were the artists, who had varying reactions to the conflict around their work. Andres Serrano said that the first attacks made him feel isolated and he tried to stay away from the press but the attacks on Mapplethorpe’s work which followed at least gave him allies. Jesse Helms was a lot of things to a lot of people, but he was good to me, said Serrano. He also pointed out that the government got a good return for the $5000 of federal money he received through the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (which exhibited Piss Christ); his career was successful and he’s paid lots of taxes.

Performance artist Tim Miller was one of four recommended for NEA grants by the professional advisors and later rejected on political grounds. The four took the NEA to court and won; the court declared the NEA could not censor awardees. But the greater political war was lost when Congress cut 40% of the NEA’s budget in 1995 (it still has not regained 1994 levels) and NEA grants to individual artists were eliminated. Since then Miller has performed nationally, including at places where he is clearly the first openly gay representative, and he said he was willing to remove certain parts of performances which might provoke objections if it enables him to bring his message to places where it otherwise wouldn’t be heard.

Patti Smith, a close friend of Mapplethorpe’s, charmed the audience with her openness and personal reminiscences (including her ingenuous early responses to Mapplethorpe’s X-Portfolio), her poetry and songs. Like Miller she was also willing to tailor her content to her audience. Smith didn’t seem to see it as self-censorship since her larger messages were expressed elsewhere. Performance artist Karen Finlay, another of the performers who took the NEA to court, objected strongly to what she saw as self-censorship. Were she asked to change content of a performance she’d refuse to do it, but offer instead to host a discussion or appear in another format. She also recalled how extremely isolated the controversy had made her feel.

Karen Finlay, photograph © Christopher Felver/CORBIS.

Serrano apart, no one claimed the culture wars were good for art or the art world. I‘ve worked with a number of artists who create difficult work that has repeatedly faced censure and none of them ever benefitted from the experience. Fighting takes tremendous effort, is lonely work, and is time lost from those things which inspired the art in the first place. But 20 years along what have we learned? Americans for the Arts was formed as a lobbying organization in response to the controversies that began in 1989 and tries to create a national platform for the arts; but will we really be in a better position when the next controversy arises? History tell us that it’s hard to predict what will spark it, but it will come.