Ivy League star power was in evidence in two recent lectures I saw by Columbia professor and BBC video star Simon Schama and Yale Professor Alexander Nemerov.

Alexander Nemerov, an art historian, spoke at PAFA about Abraham Lincoln, and his lecture was a surprise and a delight–poetry in words and images that felt like an invocation of its subject — a seance almost.

Lincoln is the American president whose name comes up most when linking President Obama to any of his predecessors so I wondered if Nemerov would go there. He didn’t, not directly but maybe by indirection. Nemerov’s talk was, instead, a rumination that delved into Lincoln as symbol, guiding light and moon-like cypher.

Curator Robert Cozzolino introduced the Yale professor by saying he was an inspiration to art historians everywhere for showing how to write from the gut and pursue what’s in the work instead of following the safe path of building on what others have written before. Nemerov’s imaginative readings of art have expanded what art historians can do, Cozzolino said.

And indeed, from the start the lecture followed a different path from other art history lectures, many of which tend to be lists of works that build up to a big pile without a lot of big ideas. Here, Nemerov showed few slides in his hour-long talk. And each slide hung on the screen for what seemed a long time, allowing the mind to wander around the image while words filled the air.

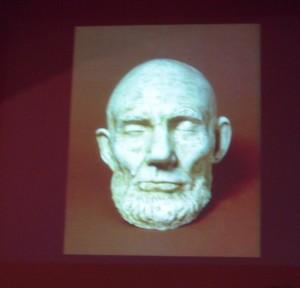

The first slide was a life mask of Lincoln done by Clark Mills two months before the president was assassinated.

Apparently, Lincoln was a morbid guy — and superstitious, too. He dreamed his own death repeatedly. So for him to have a life mask done was not shocking although today it seems spooky. Interestingly, a life mask looks pretty much like a death mask–and both call into question the whole life/death dichotomy. Many people see Lincoln’s life mask and think it’s a death mask. Of course the hindsight that this mask was made so close to his death adds a level of frisson to the object. Nemerov pointed out that Lincoln looks bald but of course he wasn’t. He wore a skullcap while undergoing the plaster cast and it gives him a (deathly) skeletal look.

Nemerov talked about how Lincoln and the nation came to be as one and how the “[Civil] war came to rest on his face.”

The mask was for Lincoln 30 minutes of respite from the world, Nemerov said.

Lincoln had a belief in “presence,” a here-and-nowness, a being in the moment, Nemerov said. The Gettysburg Address, 262 words long, includes 8 instances of the word “here.”

The slide changed to a David Plowden black and white photo of a tree. The image is bleak and old looking although the photographer is contemporary.

Nemerov said that Lincoln felt trees were a presence. The president was known for talking about a tree before him and saying that it reminded him of other trees but mostly of the one here before him. He exercised “slow cold clear perception,” Nemerov said. He liked trees when they were not in leaf. He liked that you could turn a tree into a metaphor but it was still a tree. The world was not a passive character in Lincoln’s life. The world invaded his space (a tree branch brushing against him, a leaf falling) and he loved it.

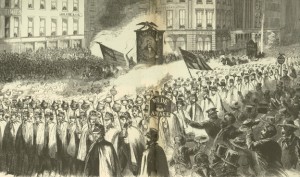

New slide of “The Wide Awakes,” avowed Lincoln men, marching at night with torches.

The most powerful presence came from light, Nemerov said. There’s a difference between big light and a solitary light, a singular flame. Big light illuminates all and throws all into clarity. The Wide Awakes marching together was one big light that was a prelude to illumination of the whole land he said. The picture in the newspaper spread throughout the country.

One solitary light divides…A man burned to death in one fell swoop ; Lady Macbeth’s candle is the essence of grave isolation;

Lincoln saw Donati’s comet in 1858…Herman Melville wrote The Portent, in 1859, a poem in which he calls the abolitionist John Brown hanging in a tree “The meteor of the war.”

The comet is a flame that does not illuminate.

The moon is light. People link Lincoln and the moon. Pictures of the moon are like the life mask or like photos of Lincoln late in his presidency (ravaged face), he said. The moon has the glow of folklore and the reality of life. So close up it’s ugly. Too close up it’s “astronomical pornograpny.”

The moon has star power which eclipses all else–plot, meaning. “I think of Lincoln in that way,” Nemerov said.

Seeing a gas lamp in front of Ford’s theatre (a replica of the originals) made Nemerov think of history. History is a journey into intensity and the solitary. History is to help people see something they’ve never seen before.

In the Q&A Nemerov showed some humor saying a historian is a folkloric or necromancer.

It was a strangely moving talk and risky, pulling from folklore, science, history and art and its big point seemed to be the complexity of life and the mystery of living on earth in this time and the true impossibility of capturing the past in history except via poetic means.

Simon Schama is known for his books of history and art history, and for his 30 tv shows, including The Power of Art. He spoke at the Free Library about his new BBC series (and book), The American Future, a History, about the 2008 US election. Sadly, his talk was a disappointment for being too much self-promotion and not enough there there. Before the lecture began we were treated to the trailer for his new BBC series and it felt like a warm-up for a sales pitch, and it kind of was.

Schama is a charming in the English Don mode. His talk was filled with bon mots, quips and endearments to the audience. But his thoughts on the election replayed what everyone already knows if they were watching — that more people voted in the election than in recent past elections and that Obama is significant for being our first African American president. This was not news and either he wasn’t sharing any of his nuggets of gold or there weren’t any but the talk didn’t go any farther.

He did say that journalism is history’s “first draft,” and that seems right to me. But in the context of this sales pitch-y talk, the assertion seemed to be too much justification of his own journalistic tv projects.

Unlike Nemerov who seemed to imply that inward looking imaginative leaps were a way to get to historical truth, Schama castigated history delivered by seers sitting in ivory towers.

Surely there’s room for both at the history (and art history) table. But unless it’s rigorous is it really history? Is Shama’s BBC program not just the first draft waiting for the seers in the towers to give it some heft? I guess I like rigorous historical writing but I vote for that poetic imaginative seer who makes intuitive leaps which I think are necessary to getting at the truth.