Kent Monkman’s video installation Dance to the Berdashe begins in darkness. Four projection screens decorated with tassels and shaped like bear hides surround a central screen. A gloved hand appears drawing simple icons of different natives on the surrounding screens. The larger-than-life drawings become animated dancers and then come to life by overlay of human figures, bringing the viewer into a live filmed ritual.

As the natives dance to traditional aboriginal music, they morph into gentleman/native hybrids, sporting umbrellas and top hats. Bowing down to the central blank screen, the dancers grow weak and blurry, while Monkman appears as the central figure of the Berdashe, a man dressed as a woman. As the music becomes trance-like and contemporary towards the end of the 12-minute dance, the men dance in synch with the Berdashe, spinning to a final electrified moment of power and divinity.

As a viewer, I was left in awe, curious about this central figure and his/her power.

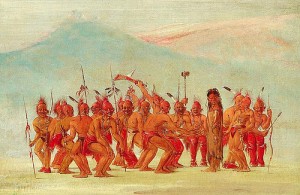

The piece by the Toronto-based Cree-artist Monkman, on display at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art (MMFA), was created in response to artist George Catlin’s reaction to the male/female figure he encountered in his travels documenting Native Americans in the early 1800s. Witnessing the dance, Catlin called it “unaccountable and disgusting” and even went so far as to “wish that it might be extinguished before it be more fully recorded.” (1) While his statement very strongly dismisses the custom, Catlin’s painting Dance to the Berdashe seems innocuous. This painting shows native men dancing around a male/female figure. One dancer appears shocked but otherwise the others seem celebratory. While seemingly innocuous, it is what is not painted that illuminates the impact of the European point-of-view on the conception of Native peoples.

What image comes to mind when you hear the term Native American? A stereotypical image à la Pocahontas? A stoic, strong, painted and feathered hunter? Where do these images come from? The Western eye and consequently Western art has arguably oversimplified and misrepresented Native people. Monkman, in his oeuvre as painter, performance artist and filmmaker, tries to revisit and complicate this history by offering another point of view.

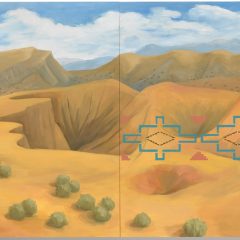

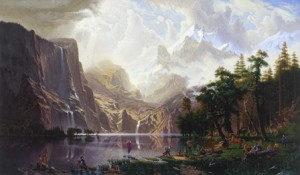

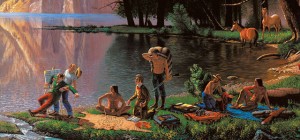

In a painting, on display in an adjacent room at the MMFA, Monkman has masterfully recreated Albert Bierstadt’s Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868). Or so it seems. Upon closer inspection, the majestic scene is actually populated along its lower edge by buff half-naked settlers, well-coiffed gentlemen, casual natives, a cross-dressed man posed as a Botticellian Venus, as well as Westerners pretending to be Natives for a photographer. The work, entitled Trappers of Men (2006), wittily, humorously and masterfully pokes fun at history/colonialism/gender/sexuality/representation. A plaque below the painting attributes it not to Monkman but to his alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testicle.

Monkman challenges his viewer to rethink the history they think they know. Dance to the Berdashe reveals a simple, pure ritual, yet it does not mine the questions of reinterpretation of history fully. Berdashe, as I later discovered is actually an extremely derogatory denotation, deriving from the old French word bardache, meaning gay male prostitute or passive sodomite. Monkman fails to really educate his viewers and tell them this definition. He does not mention the now politically correct term two-spirit or the privileged role of these male/female figures in Native communities.

While his video installation and accompanying text create a dissonance, they fail to really educate the viewer. The act of posing the question What is our History? is indeed important in stimulating dialogue and paving the way to greater intercultural understanding. However, I wish that, beyond the questions, Monkman had provided some answers so that the process of education he very aptly catalyzed could have gone further.

(1) George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, London: 1844.

More on Monkman here; article by the artist and his alter-ego here; and more about Two-Spirit (or duo-gender Native Americans) here.