Marcel Duchamp’s final masterpiece Étant Donnés at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is an art historical conundrum, inviting speculation, adoration, revulsion and religious pilgrimages, sometimes all of these reactions at once. The peephole installation, which permanently resides in the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a reclining nude, legs splayed for a nearly full-Monty view, the figure nestled on foliage in a 2- and 3-D landscape diorama with a mechanized waterfall. Not surprisingly, it invites comparison not just to Dejeuner sur L’herbe and all the other art historical nudes, but also to an inflatable sex doll!

Into this problematic morass, Michael Taylor, the effervescent curator of Marcel Duchamp: Étant Donnés, the art historical exhibit of the work and related objects currently on view at the PMA (see Andrea’s post), cheerfully waded, in a talk Friday on a rainy night in August that attracted an astonishing crowd of about 200 fans, devotees and art insiders. The full title of the piece is Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, a2. Le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas) 1946-66, and this year’s exhibit celebrates the 40th anniversary of its installation.

Taylor’s talk was a gossipy backgrounder on the history of the 1968 installation and Duchamp’s two-decade effort to create the work. Taylor manfully tackled with wry jocularity whatever vocabulary the discussion of body parts required, at the same time, promising not to take away the mystery of the piece. Shockingly, he didn’t.

“It’s the first site-specific art for a museum,” Taylor said, after laying out a story of secretive facture and politicking by Duchamp of museum trustees to get the work accepted by the PMA, then and now home to the largest collection of Marcel Duchamp’s works.

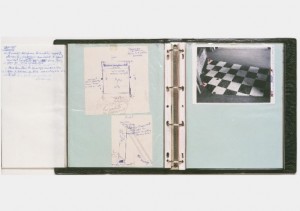

Then-Curatorial Assistant Anne d’Harnoncourt was all of 25 when she installed the piece in the museum shortly after Duchamp’s death. She was aided by Duchamp’s widow and his step-son, Paul Matisse. The installation took a full year. D’Harnoncourt painstakingly followed instructions Duchamp left at his death in a fat black binder full of written, photographic, and schematic instructions. He even spelled out the coordinates for placing the body parts on a bit of checkerboard linoleum on which the installation rests. Taylor noted how the checkerboard linoleum was the perfect choice for an avid chess player. The instructions are precise and Duchamp left only one scintilla of discretion to the curator:

“‘You can adjust the cotton wool [clouds] in the background,'” thereby allowing a change in the weather, added Taylor. Not that the cotton wool has been readjusted since the original installation. It’s always sunny in Etant Donnes!

In keeping with Etant Donnes peephole-i-ness, the piece was created in such secret that for 20 years the author of a Duchamp catalog raisonne had no idea it existed. The catalog was at the printer in Milan when the author got the news. “Stop the presses, Milan,” Taylor quipped.

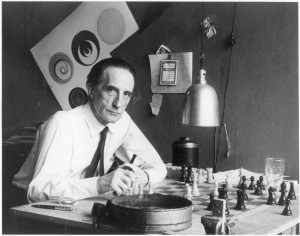

Duchamp’s secretiveness about his art began in Duchamp’s 14th Street studio, where he moved in the fall of 1943. There he welcomed visitors to a bare front room that contained only a chessboard and chairs, projecting an image of the artist as too fine and too intellectual for material practice. Unbeknownst to his guests, though, through the bathroom behind a locked door, was “a Santa’s workshop filled with all these body parts and mannequins.”

Many of the body parts, experiments with materials and castings, and “erotic objects” never before displayed, are part of the exhibit now at the PMA, where they exude a weird and fascinating sexiness.

Taylor attributed Duchamp’s motives for secrecy to a rebellion against galleries. “In 1940, he wanted to give up art–its commercial aspect. The point of Etant Donnes is it’s a secret and not a part of the gallery system.”

That was not Duchamp’s only secret of the time. He was carrying on a seven-year affair with the main model for Etant Donnes, Maria Martins, the wife of the Brazilian ambassador. “She rocked [Duchamp’s] world. …He was besotted by her.” (Access to Duchamp’s and Martins’ correspondence–provided by their estates–was critical in providing new scholarship used to create the exhibit and catalog–which includes the correspondence in translation.) But in the end, Martins refused to leave the ambassador and her busy social life for Duchamp.

The talk was full of crunchy details. Here are a few:

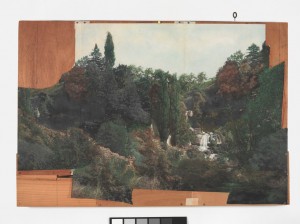

–Taylor and PMA Contemporary Art Curator Carlos Basualdo made a pilgrimage to find and photograph the backdrop’s waterfall, which overlooks Lake Geneva. Much to their dismay, they discovered the small building barely visible in the backdrop was a shooting range–still in use by Hell’s Angels. The two briefly clambered atop the roof for a quick picture or two and then fled.

–Duchamp’s own black-and-white collaged photographs of the scene defied his attempts to paint them over. A year later, he met Dali in Spain and enlisted his help with the background. Dali made a series of collotype prints of the image that were more paint friendly and became part of the installation.

–When damage occurred to one of the arms during a move, Duchamp cast a new one from his wife Alexina, aka Teeny, whom he married a few years after the break-up with Martins. This explains why the arm holding the light is a little out of proportion to the rest of the figure. Teeny was less teeny. Martins and Teeny actively contributed ideas and opinions to Etant Donnes. “All three important women in Duchamp’s life are in there!” I asked Taylor who were the three. His answer–Teeny, Martins, and Mary Reynolds, another of his romantic involvements “off and on, with Duchamp from the 1920s until her death in 1950,” he wrote. She “probably supplied Duchamp with the parchment for the mannequin’s skin.”

–Dali was not the only artist on whom Duchamp relied for help. Joseph Cornell had helped Duchamp make the Boites-en-valises. In fact they had helped each other–Cornell and was known to go through Duchamp’s trash, looking for materials for his own work.

Taylor, discussing the phallic form of the lamp in the figure’s hand, said, “In many ways, Etant Donnes is the 3-D equivalent of The Large Glass, that great allegory of frustrated desire…Duchamp always loved contradiction. You can’t look at a painting of a nude again without thinking of [Etant Donnes].”

After the talk, during a brief Q&A, someone asked about the deformation of the figure’s genitals. “They are strange,” Taylor said. “Having never cast my genitals, I can imagine it’s a difficult area to cast. Is she a woman?” Taylor then mentions Duchamp’s interest in transgender roles and Rrose Selavy. “My own gut feeling is the deformations happened in the casting process and Duchamp kept them because they were in line with his notions about gender. What I don’t want to do is look at Maria Martins down there.

“Next? [a pause while no one asks another question]

“Well, that’s a very good way to end it.”

On Sept. 11-12 the Philadelphia Museum of Art is holding The First Annual Anne d’Harnoncourt Memorial Symposium in conjunction with the exhibition, including a talk by artist Jeff Wall on the influence of Etant Donnes. The exhibit, which celebrates the installation of Etant Donnes at the PMA 40 years earlier, and the catalog are also dedicated to the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, the beloved director and CEO of the museum, who died last year.