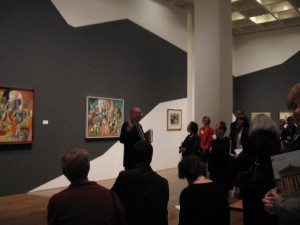

The Gorky retrospective that opens tomorrow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is an eye-opener–one of those exhibits that shows the artist as a thinker, working out problems and solving them. To see the drawings (and the gorgeous and bold handling of line in them)–sometimes multiple drawings–preparatory to paintings is wondrous, at once belying the idea that the paintings are casual and improvisatory abstractionist expressions and belying the idea that the paintings are static reproductions of the drawing ideas.

At the same time, the show gives a view of the path the Armenian-born Gorky followed, from his early paintings to his last. So naturally, being a bit of a contrarian, I fell in love with what has been regarded as a byway in his painting career–a group of relatively cool-affect, mural-size paintings he created for Newark Airport under the WPA program employing artists. These paintings are almost a counterweight to the usual skinny on Gorky–an intellectual yet a man of deep passions, struggling his way through his difficult life via art.

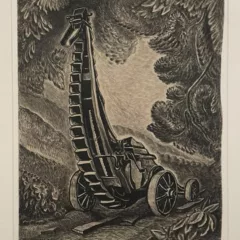

The enormous works on canvas are super-flat super-graphics of a sort, inspired by machinery and aviation and the plan of the airport, with the same belief in the power of technology that imbues Leger. The paintings (there were 10 in all but only two, both in the show, survive) have a can-do American optimism in their straight-ahead flatness and color.

These paintings were discovered in the 1970s under 14 coats of housepaint when a workman, removing an exit sign, noticed a strand of canvas clinging to one of the screws. When Newark Airport had been turned into a military base during World War II, the general in charge ordered the works painted over–an ironic outcome for work that clearly was based on the understanding that the audience would be travelers, not art lovers. The murals had been up only four years.

The colors were wrong in the first conservation of the paintings shortly after their discovery, said exhibit Curator Michael Taylor as he told the story of the murals at the press walk-through. So here they are, re-conserved for this exhibit at the behest of the PMA, looking glorious and ahead of their time.

After I left the exhibit, I decided they were less of a byway than I had imagined as I wandered through the show. The flatness, the distorted geometries of the forms were all there in Gorky’s earlier abstractions, which were less painterly than the sexy, lush brush work of some of the later works.

That architectural sensibility got picked up in the supergraphic that Taylor used to draw together the galleries that hold Gorky’s later work–a fabulous almost human form stretched horizontally like a river goddess against which the paintings, now full of squiggly forms, pop in contrast. The form is based on a form painted on the walls, ceiling and floor of a 1947 gallery show at Hugo Gallery in New York, featuring Gorky and seven other artists, including Roberto Matta, Isamu Noguchi and Wilfredo Lam. The original was by architect Frederick Kiesler.

By the 1970s, supergraphics became an architectural commonplace, almost as if the aesthetic of the paintings has reemerged as American visual vernacular. Jody Patterson’s essay in the exhibition catalog recounts that the 10 Newark Airport paintings originally were greeted with opprobrium. It’s the old story of the brilliant artist ahead of his time. I think a contemporary public would not react that way, the abstract strategies of these paintings now being familiar and widely accepted as a means to communicate, used everywhere, from brochures to fine art.

Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, will remain up to Jan. 10, 2010. Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, the 400-page catalog that accompanies the exhibit reflects new scholarship–biographical details and newfound art–with essays by Taylor, Patterson, Harry Coper, Robert Storr and Kim Theriault.