The prestigious Works on Paper show at Arcadia, which opened Wednesday, raises worthy questions about the value of art objects in the year 2009.

Exhibit juror Joao Ribas, who is curator of MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (and former curator of the Drawing Center), selected 22 works by 22 artists from 1,256 entries submitted by 567. (The press release said 22 works, but I count 23).

In Ribas’ introductory talk just before the opening event, he immediately distanced himself from the talk’s ponderous title–4 Points Towards a Present History: Knowledge, Representation, Freedom and the Subject. “The real title is, Things I Have a Problem With.” That got a laugh.

Ribas spoke like a man with too many ideas–he started and restarted sentences, redirected them and then trailed off to begin again.Yet he still delivered a coherent talk, exploring aesthetics, the suspect reality of images, and the evolution of art objects as things that reflect symbolic value and freedom (of the artist) to make choices that don’t necessarily further society or its commercial ambitions.

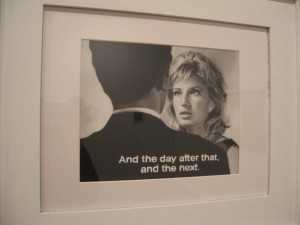

The aesthetics part of his talk was charming–including his projection of David Attenborough’s BBC bower bird video. And the bit about suspect reality in art and images became especially interesting when he brought up Islamist beheadings on video as indisputably real and as the “most iconic images in contemporary culture.” (The shakiness of Truth in art was another important theme underlying his selections for the show).

But it was Ribas’ synopsis of the history of the value of art that interested me most. Here’s my synopsis of his synopsis (this is sort of like crunching down an image on the computer so it’s still recognizable but barely–and of course this too is highly suspect).

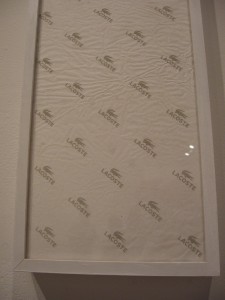

The story goes that society, hellbent on creating utile things that it values and needs, has no intrinsic commitment to art. So art is outside the needs of society. And art objects reflect freedom of the artist to operate outside the needs of society. Art represents “radical individual will–the antithesis of what was associated with capital [i.e. money].” So in the 15th century, a division grows between utile valuables provided by the craftsmen of the guilds and non-utile products of artists.

The freedom required in making art, the freedom to make choices and refuse others’ wishes, “creates a class of object that can’t fit into society in the normal way.” It cannot be priced in the same way ordinary goods are priced, and it is not based on consumer needs.

This history leads artists to later “commodify themselves as bohemians,” Ribas said.

As a symbolic marker of wealth rather than a manufactured product for consumers, art takes on a utopian identity, Ribas suggested, precisely because it is made outside the assembly line.

Technology, however, has messed with this evolution of art as a symbol of value and freedom and mystical power. “Everyone can express himself through technology. …Technology changes how freedom is expressed. The consumer is also the producer.” At this point, Ribas brought in an aside (or maybe not at aside, it being very much to the point) that the World Bank defines wealth as natural capital and creative capital.

With technology, the concomitant sharing/reproducibility and loss of copyright control give every ordinary Joe freedom to choose. How do you preserve the model of authorship when all around us that model no longer applies? Ribas asked. “The artist no longer has a place of privilege With sharing, now everyone has choice.”

Post on the show next!