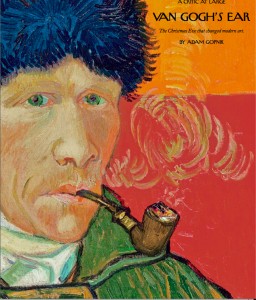

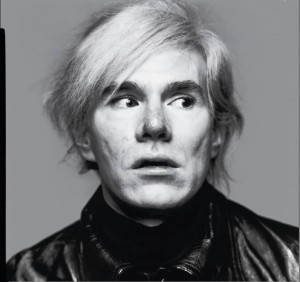

The last few weeks the New Yorker has been particularly rich with visual arts coverage, with an essay on Jan. 4 by Adam Gopnik about Van Gogh’s severed ear and now, in the upcoming Jan 11 issue, Louis Menand’s essay about Andy Warhol. Both essays make great reading each in its own way, with Gopnik fascination with van Gogh’s need for solitude but love of community; and Menand’s dissection of Warhol’s illusionism. The news here is that these two writers, who have large followings since they’re so good at whatever they write, can steer a discussion of art that probably reaches folks who don’t read Peter Schjeldahl, although he, too, is in the New Yorker most of the time.

Bringing art out of its tight little niche and into a broader sphere of discussion is something that needs to happen more if art is to get back to being approachable, discussable and enjoyable to the majority instead of the minority.

The most interesting thing I picked up from Gopnik — a great public speaker by the way who paces the stage like a talk show host when he’s taking questions from the audience (we saw him at the Free Library talking about Lincoln and Darwin) — is that van Gogh wanted to start an artist’s community and felt strongly about it. That’s what Paul Gauguin was doing in Arles living with Vincent. He was sent there by Theo to help Vincent feel like he was in a community. However, van Gogh was pretty hard to live with and the story reported by Gopnik (based on recent research in Germany) is that Gauguin — who owned a couple of swords and was not averse to using them — sliced off van Gogh’s ear in a fit of temper and that they both were ashamed and guilty and covered the facts up. “You always begin with a dream of community— Braque and Picasso in the bohemian hermitage Bateau Lavoir; the handful of painters brave enough to go abstract in the Cedar Tavern—and end with a reality of competitiveness and assault, suspicion and estrangement,” says Gopnik about the artists need for community. Well, let’s hope it’s not always…which is a rather downbeat view of things. But Gopnik’s list is a nice reminder that artists do feel the need to come together, something true today as in the past.

What I love in Menand’s piece is how broad it is, moving from biography to discussion about the art and to what’s been written about the artist and the art. I learned, among other things, that Warhol read a book about the Bauhaus that sang the praises of mechanical reproduction of art when he was in college, and young Warhol — who later practiced mechanical reproduction of art like nobody’s business — was very enthusiastic about what he read. Menand also talks about a new article by philosopher Bertrand Rouge who posits (in response to Arthur Danto) that Warhol’s Brillo Boxes are not any more philosophical objects than a Pollock painting is. And, unlike Duchamp’s readymades — which Rouge sees as philosophical objects — Warhol’s Brillo Boxes are tromp l’oeil objects that continue the tradition of art doing what it does best, namely creating illusions about reality. “The Brillo boxes did not break the illusion-reality barrier at all. They were just one more move in the game; they didn’t bring it to an end,” according to Menand.

Whether or not you agree with what the writers say, the essays, with their nice, full-page illustrations, offer vernacular discussion about art topics most people don’t think about in their daily lives. And how great is that? A little talk about art is good for the soul, especially at times of war, recession and uncertainty.