Picasso and the Avant-Garde in Paris at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through April 25, 2010 is a remarkable exhibition for two reasons. Most importantly, it emphasizes the strength of the PMA’s collection in the area of early Modernism; secondly, it has the public paying a special admission fee and standing in line to see an exhibition whose most important works, unless on loan elsewhere, are on permanent view in the museum’s galleries. The exhibition is neither a definitive view of Picasso, nor a serious study of the Avant-Garde in Paris during the first half of the 20th Century. Even restricted to work from the PMA’s collection, I don’t understand the omission of Matisse’s portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (although I suspect it is on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago for an exhibition of Matisse’s work from the teens), or works by Calder, Mondrian or Torres-Garcia, to name examples that come readily to mind, all of them more important than most of the artists represented.

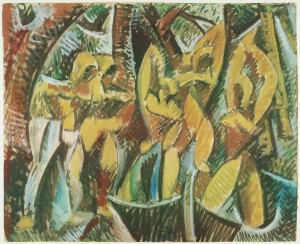

This review is directed at visitors with a serious knowledge of the PMA’s collections and is both limited and idiosyncratic, so I won’t mention the many great paintings by Picasso and others that have simply been moved from their usual galleries. The exhibition will be well worth attending to see significant works on paper by Picasso as well as several very interesting works that are rarely, if ever, on view. None of them are discussed by the audio guide, so you’ll have almost no competition in viewing them. Right at the beginning are three splendid Picasso watercolors with connections to important paintings: one is a well-known study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon; Nudes in a Forest which I think is related to the great Three Women in St. Petersberg; and Three Nude Figures whose female nude, elbow aloft and veering from lying to standing, may well be related to both paintings.

The following room has several Cubist drypoints by Picasso; I don’t think them major, even within his graphic work, but they are wonderful examples of the technique and worth knowing. In the following gallery is Picasso’s Still Life with a Violin and a Guitar, which is a textbook example of why the Cubists (and several generations of modernists) rejected varnishing their work. Note: none of MoMA’s Cubist Picassos have retained their matte surfaces, so we should be grateful for the many unvarnished modernist works at Philadelphia. Varnish would not only even out the intentional surface differences between the collaged areas and the painted ones (some of which have sand included,which gives the appearance of an out-doors wall); but the contrast between the painted areas and slight bits of visible raw canvas would disappear.

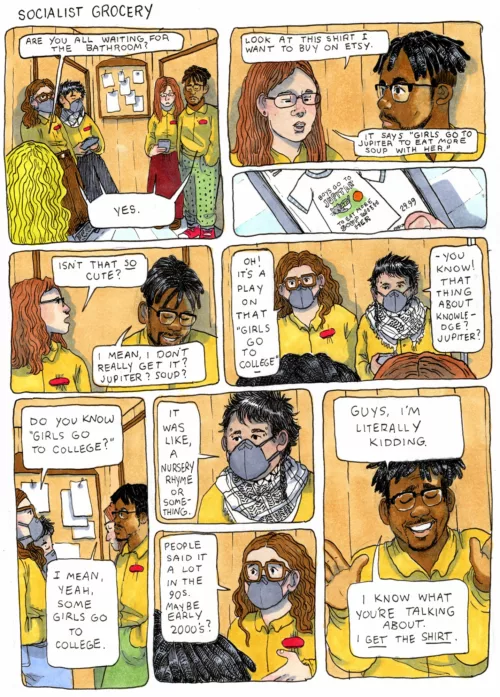

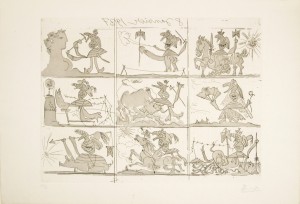

Skipping several large galleries to the one marked Picasso and Surrealism is a small and unimortant Masson, Italian Postcard (1929), but with the most wonderful frame by Pierre Legrain! The same room has several of Picasso’s minotaur prints, which are some of his best. The Blind Minotaur, an aquatint that resembles a mezzotint, has particularly velvet-y blacks, while Minotauromachy anticipates Guernica in many ways. The woman standing next to me didn’t think that the Minotaur was caressing in Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman; decide for yourself. Then, if you don’t know Dream and Lie of Franco (it and Guernica are Picasso’ s only foray into directly political art, both done in aid of Spanish Republic), you should see it here. It’s multi-panel narrative also allies it to the format of comics.

The last piece I’ll mention is Sonia Turk Delaunay/Blaise Cendrars’ collaboration on the printed version of Cendrars’ poem, Prose on the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jehanne of France (1913). The text runs vertically and unfolds to more than six feet. Delaunay’s imagery was done with a stencil but shows the effects of hand-manipulated inks; it could pass for watercolor, and it’s gorgeous!

Understudies

I decided to check out what the PMA had hung in its now-denuded galleries devoted to modernism. The first two which usually show the Cubist work are exhibiting a group of paintings by exiled Russian modernists, collected and donated by the critic, Christian Brinton. They’re an interesting assortment and not likely to make another appearance in toto. The star of the group is David Burliuk, an artist of widely-divergent styles who was known as the Father of Russian Futurism (which, as far as style goes, means Cubism). He was also a terrific dandy; photos survive of him in top hat and facial tattoos (impermanent, I presume); one can easily Google them. The Brinton collection includes a portrait of Burliuk by Nicol Schattenstein in which he wears one earring and a vest, the right half of which is red, the left green.

The second gallery has a minor selection of Mexican modernist work, the stand-outs being Dr. Atl’s 1928 self-portrait, a small terra cotta Mother and Child (1954) by Elizabeth Catlett and Siqueros’ War (1939), made after he returned from Spain, and most definitely anti-war. Further back, in the hall leading to the rooms of Duchamp, Brancusi and Twombly I found a fascinating little painting on glass, Chinatown (1917) by Joseph Stella,which is every bit as modernist as Max Weber’s better-known work of the same title. Even if Stella didn’t produce the work in Paris, it clearly reflects his exposure to Parisian modernism.