Philadelphia artist Jordan Griska’s ambitious solo show, Nowhere Fast—his first since winning the 2008 International Sculpture Center Outstanding Student Award—showcases his ability to turn an understanding of industrial fabrication into seriously high-impact sculpture. Unfortunately, whether due to the particularities of the University Science Center’s Breadboard space—more of a corporate lobby than an art gallery—or attempting to combine older work into a new theme—Griska’s ISC Award-winning Ad Infinitum piece is back—Griska’s show does not live up to the potential the best work suggests he has.

Griska’s title, Nowhere Fast, sets a tone just this side of mid-20th century existential angst. His choice to render it in neon tubing, as a discrete piece, tips it over the edge.

Putting a contradictory declaration in neon is a number from the post-modern bag of tricks that has gone from a radically distanced yet familiar way of making a statement to a common choice at risk of triteness.

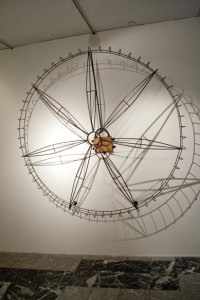

Griska’s largest piece, Icarus, spreads itself over much of the main gallery. It is a mostly steel apparatus that is equal parts exercise bike, Mark di Suvero, and space shuttle landing. In addition to the apparatus itself, there are three large photographs entitled Sisyphus, documenting a performance that used the machine.

The Sisyphus photographs are striking. The performer, clad in a bodysuit and helmet, assumes a sporting stance, seemingly at the ready, and prepared to go for the win! However, the clear immobility of the machine and the overwhelming presence of the outspread silver parachute make the ambition suggested by the figure’s stance and costume seem deflated by comparison. In the pictures, the simultaneous arrest of ambition and movement is echoed by the stillness of the photographs. The dramatic lighting and centralized compositions provide this further level of precarious stillness: if the lights were just slightly different, or the camera pointed just a little to the left, the picture might feel like a snapshot instead of staged photography.

However, Griska’s excellent photographs are dominated by the Icarus apparatus and the other sculptures in the show. These physically large pieces lack the metaphorical weight of Griska’s more successful performance documentation.

Icarus, in particular, is more a collection of props than a coherent work. The parachute-machine’s propeller cage, hung and lit on its own wall, feels especially flat. The cage’s separation from the standing machine and outspread parachute on the floor makes Icarus barely readable as one piece.

A generous reader might try interpreting the cage, bike-pedestal, and parachute in the terms of the Icarus myth—a kind of warning about ambition overstepped—yet it’s clearly also linked to the nearby Sisyphus piece, which has a less moralizing and more ambivalent relationship to ambition. Should I just read it, then, materially? It is, on that level, a number of deft, deliberate steel constructions, vaguely reminiscent of some minimal artwork.

Yet, it is hard to consider it’s physical properties alone, as Griska has worked his sculpture into a messy symbolic tangle with both his Sisyphus piece and the Icarus myth. Unfortunately, by linking this confused sculpture to the tenser symbolism in his photos, Griska also threatens to loosen that carefully strung set of associations.

In fact, each additional piece I saw in the show further explained away the exciting and controlled tension of Sisyphus. A pattern emerged: a device designed to create a determined interaction with a body—the parachute, exercise bike, etc.—would be re-presented in the artwork, essentially unmodified, but now made decorative or functionless.

The denial of function and play with bodily regulation are, indeed, powerful artistic tools. As I’ve said before, such challenges to the conventions of rationalized life make the for best works of art.

But precisely because these methods are now so well understood as signs for “art,” in order to continue their fight, artists must be careful not to merely cite them, but actually create new, hard to describe, modes of challenge.

Griska’s most puzzling—and by my rubric, then, most successful—piece, had little to do with function or the body at all. His piece Ad Infinitum, a loop of McDonald’s PlayPlace-like tubes—if read along with others as an absurdist take on the control of bodies—is a bit of a one liner. However, it was originally made not as a part of this show, but for his 2008 senior project, in quite a different context.

Looking closely at the details of its material existence, Ad Infinitum offers much more than the sum of its parts.

The surfaces of the slide-tubes now have lights clinging to them instead of sweaty kindergarten palms. The constellation of lights, mirrored in the veined marble floor, truly becomes a phantasmagoric image, all the more arresting because it is both easy to see how it produced and impossible to predict its complexity. Further, the geometric lines connecting the lights on the piece are painted in conductive silver ink, giving them a strangely hand-drawn feel where I was expecting mechanical precision.

Imagining Griska scrawling those lines on that plastic for hours provides is a truly odd image. Perhaps in the future, Griska will be able to capitalize on his clear material sensitivity to generate more novel approaches to his critiques. Nowhere Fast is on view at the University Science Center until June 25th.

![Collaborative Research [RE]Imagining Art at New Esther Klein Gallery Exhibit 9 artblog reimagining science 3](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/2018/02/artblog-reimagining-science-3-240x240.jpg)