I’d met Beauvais Lyons and been aware of his work before I met my friend, Barbara, in the garden opposite the Museum of the American Philosophical Society (APS) where Lyons had set up his display last week (on through tomorrow). Most of those who stopped by, however, had no reason to know this wasn’t another educational display within Independence National Historical Park.

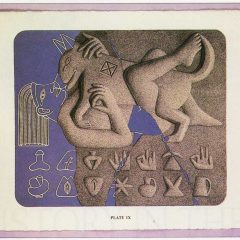

Lyons is a tall, sober man dressed somewhat anachronistically in a straw boater and bow-tie, and often has a Bible tucked under his arm. He walks up to the visitors, hands them his pamphlets and says Here, have some propaganda, and proceeds to guide them around the display, drawn from the Hokes Archive. It is, he explains, devoted to zoomorphic juncture e.g. hybrid animals whose top portion is one species and bottom portion another (like W.S. Gilbert’s character in Iolanthe who’s a fairy down to the waist and a man below).

The pamphlet describes the Association for Creative Zoology, dedicated to understanding the beauty and complexity of God’s creation and ends with the 104th Psalm: O Lord, how manifold are thy works! Lyons begins his tour with Biblical and historical precedents (dragons, unicorns and satyrs), which provide textual documentation of zoomorphic junction, before turning to modern examples. These are depicted in lithographs and on a Ming, blue-and-white, porcelain dish. But the most compelling examples are certainly the stuffed specimens. Pointing out the ground-hog-fish, Lyons explains that the fisherman didn’t eat his catch because he suspected that gamey-fish might not be to his taste. At this point Barbara and I were literally hiding behind our hats, trying not to tip off visitors with our uncontrollable laughter.

Stopping in front of stuffed examples of a Pekingese dog-duck and a crow-dog, Lyons asks which his visitors prefer. Always the dog-duck!, he says, remarking that people are drawn to the more anthropomorphic features of mammals. Lyons then turns to his final evidence, certain to win over doubters: an excavated skeleton of a zoomorphic junction.

Brought to Philadelphia in connection with the current APS exhibition devoted to Charles Darwin, Lyons’ work raises the unfortunately-ongoing controversies over evidence refuting evolution, and the gullibility of a public that uses the Bible as a science text. He took the archive to the 2007 John Scopes Trial Festival, in Dayton, TN where he had the chance to show it to Creationists; he found they lack a sense of humor. If you want to believe in the Loch Ness Monster and the Piltdown Man, don’t miss the Hokes Archive!

Exhibition and Panel Discussion This Weekend

The Hokes Archive will be on view Sept. 16-18 from 11 am-7 pm and Lyons will also participate in an artists’ panel discussion, A Priest, A Rabbi and Charles Darwin Walk Into A Bar… on Sunday, Sept. 19th at 3 pm at the APS Museum; the other participants are Brett Keyser and Eve Andrée Laramée who also did projects in connection with the Darwin exhibition. Lyons is a professor of printmaking at the University of Tennessee whose courses include one on pranks. A video of Lyons and the Hokes Archive at the Scopes Trial Festival can be found on You-Tube.

Problemy: The Dufala Brothers at Haverford College

Steven and Billy Blaise Dufala’s exhibition, Problemy, is on view at Haverford’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery through Oct. 8. Their work entails the same sort of boyish entrepreneurial fantasies that inspired Chris Burden’s B-Car (1977, a fully functional, extra light-weight automobile built from mostly hand-made parts) and Fischli and Weiss’ video, The Way Things Go (1987, a Rube-Goldberg-like chain reaction featuring tires, ladders, oil drums, steam and fire).

The gallery is filled with exquisitely-crafted but distorted, domestic objects: a hammer whose handle is sized for a giant; a typewriter with a keyboard filched from a Blackberry; a living-room set whose un-covered upholstery is made of pink, fiberglass insulation; a large broom formed to fit the profile of stairs. Then the photographs, large and lush (as is the current mode) which depict the equally unlikely: sports shoes that have grown, like Pinocchio’s nose, so their toes loop around and around into snail-like forms. The Dufala’s adaptive re-use yields use-less objects of contemplation. Or art.

And then there are the drawings: exquisite, large forms that on close inspection are composed of delicate renderings of empty, plastic drinks bottles tethered together; a typewriter made of topiary; the Free Wall of take-away drawings (individually-signed multiples) depicting the scatological, sexual, playful and silly (the young woman tending the gallery said these were a favorite with Haverford students).

Two large pieces were sited out-of doors: on the building’s exterior a tubular, aluminum vent connected to an air-conditioner compressor morphs into a huge set of letters, F-R-E-S-H, before returning to tubular form and running up and into the stone wall; and largest of all, a full scale suburban house, complete with bay window and chimney, made of chain-link fencing and outlined in fence-posts. Its form resembles an idealized child’s drawing.

Text in the exhibition catalog and press release suggest that the Dufalas’ work is concerned with trash, waste and our commodity-centered culture. But for me the exhibition comes across as a celebration of the imagination and freedom of adolescence, when ideas are generated for the fun of it or just because, and objects are cobbled together to see what might happen. At that age you’re invincible, and nothing really matters.