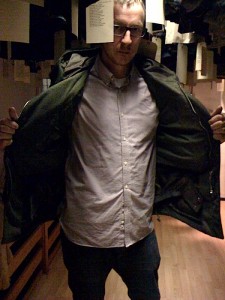

It’s hard to be a bad boy in the art world these days, but Mike Ballard is trying. His installation “Whose Coat Is That Jacket You’re Wearing?” fulfills a contemporary art world wet dream: A crowded display of illegally-gained goods (Armani, Diesel and other expensive brand name leather jackets, parkas, sport coats) and their contents (cash, drugs, cellphones, jewelry), all tagged, cataloged and reeking of human body odor just waiting to be returned to their rightful owners in a month-long act of contrition. What’s not to like?

Ballard says he lifted the jackets in a decade-long revenge binge, nicking them from pubs, and once back in his studio, emptied the pockets, cataloged the contents, scribbled poetic notes about each item and never told a soul. The artist’s kleptomania, inspired by the theft of his own prized blue Diesel 55 jacket when he moved to London from North Wales, came to an end in 2009 when he sought therapeutic help.

“I’d saved up for it,” says Ballard about his own jacket, “It was hooded, cost me about 150 pounds and was stolen from The Griffen, a Shoreditch bar, an old boozer type pub. It made me livid. So I went in the same area looking for my jacket… it was winter and I was a bit cold, but I didn’t find any like mine.”

Ballard did find others, however. Lots of them. Since 1999 he’s walked out of crowded pubs with more than 200 jackets by simply putting them on – his own jacket on top – and sailing out the door. Cheers, folks!

And now, a week before the annual London art orgy – the Frieze Art Fair – Mike Ballard lifts the veil on his secret store of stolen jackets, asking the world to come and get them, to please forgive him, and at the same time lift his star high above the door as he exits through the cloak room, a nod to fellow Brit guerrilla street artist Banksy. The installation in the abandoned Walker’s Tailor shop near the Great Portland Street tube station is a wall-to-wall closet: The jackets hang from the ceiling like sides of beef, tagged, dated and numbered, ready for pick up.

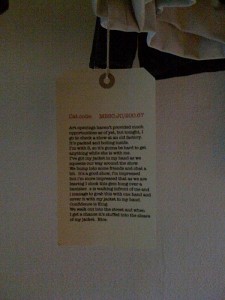

The cocoon of cotton, wool, leather and nylon is impressive in this tiny store. You can’t stand up without getting lost in the stink of beery bars, smoke and body odor which is overwhelming. (The artist is considering spraying Febreze around to deodorize the show, but remains undecided.) He hasn’t worn any of these jackets since he stole them, nor has he smoked any of the hash or spent the cash (about 1000 pounds) he’s found in the pockets; nor has even thought about selling off the diamond ring he discovered. Instead, Mike Ballard turned into an archivist of sorts, cataloging everything down to the loose rolling papers and 2 penny coins, photographing them, and scribbling a bit of prose and poetry as well as the relevant dates and locations of each theft. The texts are printed on tags hanging from the sleeves, along with the cross-referencing numbers which, when flashed against the petitioner’s claim, will prove if in fact this is their stolen jacket.

The victims are invited to pop in, submit their request, look around, and see if Ballard’s trove includes one of theirs. While I’m not certain anyone will quite remember their stolen jacket, the one which held the diamond ring will probably find its way back to its rightful owner; the others with the incriminating hash or out of date cellphones, will linger and perhaps find their way “to a charity auction,” says Ballard.

Unlike another art world clothes horse, the thoughtful Frenchman Christian Boltanski whose installations of tons of real Salvation Army castoffs made waves in Paris, Milan and New York this past year and focused largely on memory and loss, Ballard’s is an effort to gain forgiveness and garner attention for being bad. But in a way, it does touch upon memory and loss as well.

Sam Leith, a writer for the UK Guardian raised the question that perhaps these jackets are not stolen at all, but just swiped (or worse, bought!) from a Salvation Army depot and put on display. Ballard disputes this, and argues that he’s even sought professional help for his obsession. He told the Guardian: “I want them out of my life.” Meaning the jackets, not the shrinks. He tells me: “Art and crime has always gone hand-in-hand with me. Making artwork out of other people’s property is what I’ve always done. This didn’t start out as an art piece; at first it was a compulsion, then it became an obsession, then the idea of giving them back became an installation and art piece.”

Last Friday afternoon when the exhibition had officially opened, five men in suits walked into the abandoned tailor shop where Mike Ballard had turned his obsession into an installation, claiming they were looking for a camel-colored Cromby jacket. Ballard, known for wall-to-wall graffiti installations (as well as other works on various walls throughout London), was justifiably a bit nervous they would “have a go” at him. The men, he says, had enjoyed a few pints during lunch, so Ballard’s anxiety was well-placed. After descriptions were given – time, place, contents in the pockets – it was determined the Cromby wasn’t there. “Fair enough,” said one of the men, and with a sigh of relief Ballard watched them leave. (Thus far, no one has successfully claimed their jacket.)

The questions Ballard raises with “Whose Coat Is That Jacket You’re Wearing?” are not terribly new: Art and Crime is at home in every newspaper on the planet. Artists have been appropriating (stealing) from others (many of them artists) since time began, and vandalism (graffiti) is now an art world staple (Banksy: Exit Through The Gift Shop). Thousands of fakes (Picasso, Dali, Chagall) float through the auction markets, hundreds of artists routinely rip off other artists or corporate logos in their art (Koons, Warhol), and theft of great works from great museums is almost a daily occurrence. But jackets? It does make you think … about folks heading home in the cold or the rain or the snow, angry and miserable.

I check the pickings myself, looking for a black overcoat that an ex-friend had borrowed many years ago wondering if he’d gotten it pinched by Ballard, but no, I didn’t find it; the only things I probably had in the pockets were Tums, which I’m sure if they were still there had both lost their fruity taste and their power to quell acid reflux. Mike eyes my own leather jacket with a kind of glee and finally says that yes, it’s something he indeed would steal back in the day, but not any more. “I don’t want to encourage artists to steal, or launch a wave of stolen goods exhibitions,” he adds, assuring me of his conversion to the up and up, the good and moral. I tell him I picked this beauty up in the Oxfam shop on Gloucester Road for only 49 pounds. “Nice find,” he says. “Yeah,” I say. “It was a real steal.”

The project, sponsored by The Makers Union, offers up a modest demi-confession in the press release: Speaking about his work, Ballard admits, “I’m not proud about what I’ve done, and I realize that I need to make amends and return the coats to their rightful owners.” Appropriation has long been present in the art world, but never before has a show been constructed entirely out of stolen items. “I recognize the risk that comes with doing this show, but as Picasso once said, ‘Good artists copy, great artists steal’.”

Getting caught is another story. Once, when stopped in mid-theft, Ballard explained to the owner, hey, it was an honest mistake, he recalls. No harm done, on to another pub! Ballard is after all a graduate from the elite London art factory, Central St Martins, so he understands how to complete his projects.

An article about the exhibition in Britain’s The Evening Standard got things rolling and several people, says Ballard, came in looking for their stolen jackets, but none had a good enough story to earn them the lost prize. The artist is hopeful that the jackets will all be returned along with everything found in the pockets. The police, he adds, have not come knocking at the door, no charges have been filed either. “The lawyers say that a person would have to file a personal charge,” says Ballard. In the meantime, the artist believes he’s doing the “right thing. Absolutely. There’s no moral code with graffiti. With this – a jacket – it’s personal; it’s an extension of your skin.”

And no, not just the art crowd will care about this, but those barflies and Yuppie cocktail punters from the time capsule of the Blair and Bush years. If they hear about it and care enough, they’ll come in, says Ballard, and try to get their coats back. That is, if the former owners are still alive. And if they are, think the jackets are still in fashion.

Just in case, see if any of this stuff is yours: http://www.whostolemycoat.com/

“Whose Coat is that Jacket You’re Wearing?” Dates: October 8– 23 October 2010 Hours: Wednesday- Saturday, 12pm-7pm

Location: Walker’s Tailor, 157 Robert Street, London, NW1 3QR Admission: Free Website: www.whostolemycoat.com/

Matthew Rose is an American artist based in Paris, France. His current exhibition of collage works and terribly unusual objects, Scared But Fresh at The Orange Dot Gallery in London, runs through October 31, 2010.