How do you make ordinary art into Black art? Surface Politics, [Salon Joose, October 8-November 20, 2010] asks that question by juxtaposing a series of works in the context of a black-owned gallery. Organizer Theodore Harris, who is well-known for his overt statements about war, religion, and politics, has invited artists of varied ages and media to participate. Harris collaborated with aesthetic philosopher Sharon Chestnut on this show; Chestnut and Harris will lead a dialogue on November 5th, 6-9 pm at the gallery, under the aegis of the Institute for Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics.

I have known Harris for some time (he was a resident at AIRspace when I was director there), and I was curious how he would deal with the work, some of which is less overtly political than his own. The installation plays up contrasts–putting, for example, taciturn works like those of Quentin Morris next to David Stevens’ very provocative burnt crosses from a 2005 Slought Foundation exhibit. On the other hand, Harris has also inserted some non-art objects (e.g. coins on the floor, yellow “caution” tape) that invite us to find hidden connections in the work. Could the tape mean that the works are all somehow threatening–and hence in need of being roped off by the authorities?

In addition to Morris, Stevens, and Harris, the show also includes work by Tanya Murphy Dodd, Joan Huckstep, Leroy Johnson, Nadine Peterson, Gabrial Tiberino, and Jared Wood. With generously high ceilings and white walls, Salon Joose provides a very comfortable environment in which to view the art. The one criticism I have is that too many of the pieces have been seen before in other contexts. I hope the organizers will continue to explore this territory, foregrounding new artists and new material.

It’s hard to get any blacker than Quentin Morris’ 6’ Circles (2008-09), a pair of black dots of said diameter painted in a thick blend of silkscreen ink and acrylic. Displayed in “Same: Difference” at the Academy of Fine Arts, I saw Morris’s work through the lens of formalism—bringing up some of the same issues as, say, Kasmir Malevich’s suprematist Black Circle from 1913. But at Salon Joose, one is forced to ask what these works have in common with their decidedly less minimal neighbors.

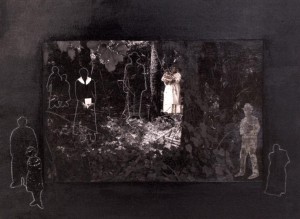

How are they like Tanya Murphy Dodd’s mysterious Embracing Light (2010), a mixed media piece adjacent to Morris’s work in Surface Politics? Dodd’s work clearly shows itself to be about the trauma of America’s racial past, and the artist’s own connection to it. The burlap used in the piece is the same type of material that, according to the Dodd, her father was wrapped in as an infant. The work arrays several Jim-Crow era photos of African Americans around the central image of an unnamed wooded area. The seclusion and anonymity of this scene give it a menacing quality: was there a lynching here? Was it a hiding place on the Underground Railroad?

Looking at Dodd’s work reminded me of Mother’s Birthday by Kara Crombie, a video on view at Vox Populi (see my post Not the Brady Bunch, 10/27/2010). Both artists deal with race, but Crombie, who is white, has no family members who experienced Southern race discrimination. Crombie’s plantation-era spoof is about how race issues have filtered down to her through popular culture. In Crombie’s art, race is a subject; in Dodd’s, the race of the artist is also a subject.

If the politics of America’s past are implicit in Dodd’s photo collage, they’re out on the surface in Theodore Harris’ works. Harris’s triptychs, some of which have been exhibited in Philadelphia before, are a collage of the symbols of U.S. abuses of power: weapons of war, police confronting protestors, the dome of the Capitol. In one recent example, War is the Sound of Money Eating (2010), the images have been applied to paddle-shaped fans that church-goers use to cool off. Other similar pieces have their surfaces riddled with oozing bullet wounds. Nadine Patterson’s work is also political, although in a less obvious way than Harris’. She too features the U.S. Capitol—and other scenes from the Washington D.C. Mall—in a statement about surveillance cameras. Her blurry video stills show how repressive police methods have become part of everyday life. Being African American, she certainly has reason to be concerned with such problems. But is artwork about the abuse of power necessarily Black? How would the same work be viewed in a Quaker, Anarchist, or Libertarian art show?

Materials can also trigger a “Black” identification. Creative people make use of what is available, and it is assumed that those who use urban materials are “urban” artists. For example, Leroy Johnson’s Heart of Darkness, a dense cluster of leftovers, is a masterful example of found object sculpture—and a perfect candidate for a “found object = Black” equation. Brian Bazemore’s Obama signs, graffitied on wood that might have been collected on a street corner, also invite that kind of labeling.

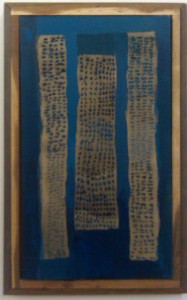

The frames of Jared Wood’s abstractions also seem to be made of found materials, but his works are otherwise closer in character to Morris’s black circles than anything else in the show. The young artist meticulously applies heavy grids of black paint to canvas; in Displacement 2 (2009), for example, the paint globules are so thick that they blend together in an opaque mass. In Displacement 3 (2010)—one of my favorites in the show—the paint dots form three long rectangular arrays on a dark blue background. I thought “skyscrapers at night” but another observer suggested “slave ships at sea.”

This situation captures perfectly the problem of naming “Black” art, and the one Surface Politics brings to the fore: without looking at the name of the exhibition, how do you know which interpretation to apply? Could“Blackness” be a surface gloss that we add ourselves? In the end, Quentin Morris’ black dots don’t get any Blacker by being in this show.

Artist Panel November 5th, 6-9 pm; Closing reception, November 20th, 6-9 pm