There are now two stories about Hide/Seek: the exhibition, and the controversy. This piece will cover the first; a second one will address the controversy. Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, at the National Portrait Gallery, (NPG) , Smithsonian Institution through Feb. 13, 2011) is a serious examination of artistic conventions, particularly those of portraiture, as they concern a subject heretofore unspoken in the polite precincts of mainstream American museums. It addresses the manner, sometimes overt but often hidden, in which sexual difference has been manifest. The artists and their sitters include straight, gay, and the fluid range of unstated, ambiguous, trans and doubled sexual identities. The exhibition and its accompanying catalog follow a sequence of late nineteenth and mostly twentieth and twenty-first-century paintings, drawings, photographs and video as they at first conform to, then ultimately reject the strictures of the most conventional of artistic genres.

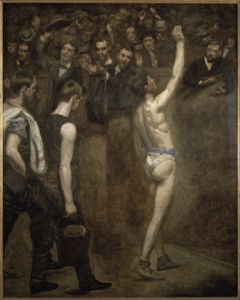

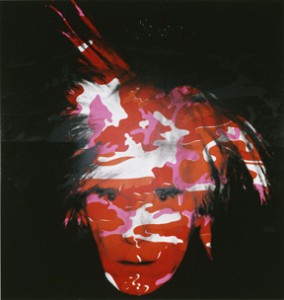

It is book-ended by two images, which indicate the looseness of the curators’ definition of a portrait. On entering one runs into Thomas Eakins’ painting, Salutat: we see the back of a slender young man, nude but for shoes and a bit of cloth which covers his loins but exposes his buttocks. He raises his hand to greet an enthusiastic crowd of properly-dressed men who ogle him. The final work, facing the exit, is a huge self portrait head of a bewigged, middle-aged Andy Warhol, overlaid by a pattern of military camouflage. The Eakins reveals a crowd that undoubtedly largely considered itself heterosexual, unselfconsciously admiring male nudity. The Warhol reveals the artist as hidden, even as his visage is exposed.

The next work is Eakins’ tiny photograph of Walt Whitman as an aged sage, in which I find no obvious questions of sexual identity. Beyond it is J.C. Leyendecker‘s illustration for Arrow shirts: two beautiful young men lounging in a gentlemanly setting, which reveals to contemporary eyes that Bruce Weber was onto nothing new. Sex always sold merchandise, even if most of the audience was blind to the actual object of desire.

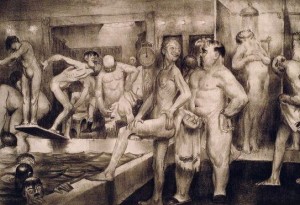

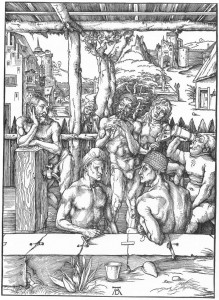

Perhaps the most startling example of willful audience (mis)reading is also the most explicit: George Bellows’ lithograph, The Shower- Bath. Jonathan Katz, in an extraordinarily clear and interesting catalog essay, reveals that the print sold out in three editions, suggesting more than a niche appeal. He also discusses the sexual mores of the period, and the fact that hetero-identifying men might maintain that identity and have liaisons with other men, as long as they maintained the male role. There’s a long tradition of representations of public baths as sites of sexual activity; note the faucet’s spout only barely occluding the genitals of the standing man on the left in Durer’s version, below. But the clearly depicted erection of Bellows’ protagonist, draped only to reveal it, goes considerably further than the Durer.

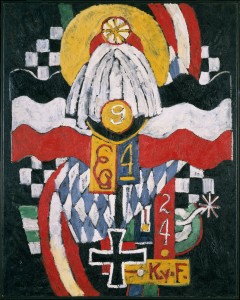

As mentioned above, the exhibition is rather free as to what it includes in the name of portraiture, marshaling images of anonymous as well as specific individuals; the inquiry into sexual coding clearly overrides that of genre, and is a sufficiently compelling subject. A number of abstractions were clearly intended as portraiture via attributes; Charles Demuth and Marsden Hartley produced notable examples. Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), one of his piles of cellophane-wrapped candy, is an intriguing revival of abstract portraiture where the resemblance is indicated, not by iconography, but by equivalence in weight. I am less convinced about Georgia O’Keeffe’s Goats Horn With Red, which appears to be included so as to allow a discussion of O’Keeffee’s consistent denial of sexual intent in her imagery.

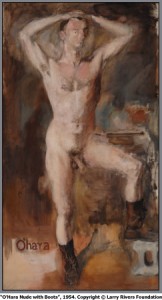

The exhibition includes some wonderful work whose acquaintance I was happy to make: Larry Rivers’ much-reproduced but little-seen portrait of Frank O’Hara (below), nude but for his boots and considerably larger than life:

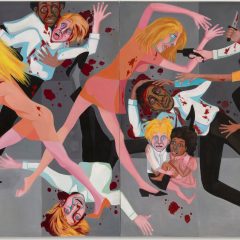

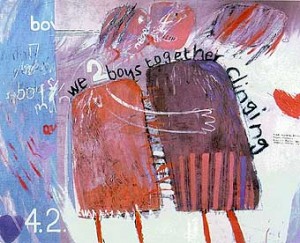

David Hockney’s Two Boys Together Clinging, painted in the manner of childrens’ art and done as agit-prop for gay rights when homosexual activity was against British law:

a small collage of 1965 by Robert Rauschenberg; Jasper Johns’ coded narrative, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara:

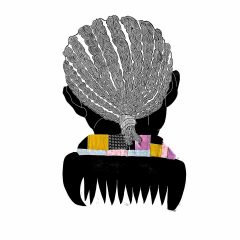

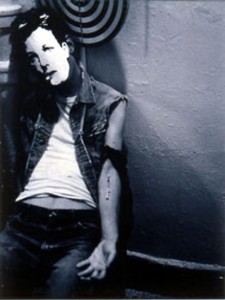

and numerous outstanding photographs, including Cecil Beaton’s arresting portrait of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Bernice Abbotts’ assured and confrontational Janet Flanner, George Platt Lynes’ Marsden Hartley, which borrows its conceit from film and is stunning, despite its melodrama, and a group of images from David Wojnarowicz’s poignant series of self-portraits as the poet Rimbaud. A provocative pairing encapsulates the exhibition’s theme of self-presentation and disguise around gender: Christopher Makos’ well-known portrait of Andy Warhol in the none-too-convincing guise of a mannishly-dressed Marlene Dietrich. Above this hangs Deborah Kass’ self-portrait in imitation of Warhol in the guise of Dietrich in men’s clothes.

The curators, Jonathan D. Katz and David C. Ward, further suggest that the social suppression gay artists experienced and their need to develop a hidden language of desire and identity was an influence in the turn to abstraction, and hence modernism, in America. I am less convinced about this – given the influence on American abstraction of Europe modernism, where identity politics had little place (unless one wants to argue for the significance of Kandinsky’s and Kupka’s origins outside major art centers) . There is certainly a history of American abstraction being used as a shield against unpopular ideas, if one thinks of the championing of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s by critics of avowedly Communist background; whether this motivated the artists they supported is open to question.

Hide/Seek explores a topic that has received serious attention in academic circles and recognition in popular culture, but almost none in mainstream museums, and the National Portrait Gallery should be congratulated for organizing it. Same sex desire is no longer a marginal subject in American culture. Twenty percent of the states allow same-sex marriage or domestic partnerships, and newspapers have been filled with tragic stories of the consequences of bullying gay adolescents. This exhibition should not be notable or brave. But it is; and that is worth taking seriously.