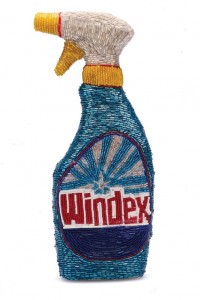

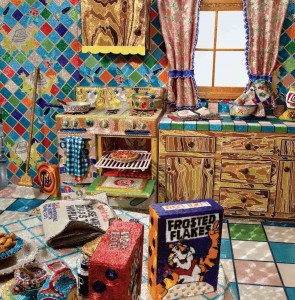

Thirty years after the advent of Pop art, Liza Lou beaded her way into art history, making pop-iconic objects and installations with miraculous numbers of glass beads applied to armatures of plaster, and in some cases, real live things like stoves. Lou labored mightily, and alone at first. Her “Kitchen,” a 168 sq. ft. beaded homage to the domestic took five years to make and 30 million beads (1991-96).

In the excellent new monograph, “Liza Lou,” the artist’s background and early beginnings as an artist are explained. Lou is the daughter of arty, born-again evangelicals who at one point burned those tools of the devil, books and art objects. Lou’s mother was artistic and brought her children to museums on a regular basis. Lou was told at art school not use beads, considered “low” art materials, but the artist, who must have a contrarian streak a mile long, went ahead and quit school and began beading.

The book has wonderful essays by Peter Schjeldahl, Eleanor Heartney and Arthur Lubow and a lively Q&A between the artist and humanities expert Lawrence Weschler. Illustrated with 200 images–of Lou’s sculptures as well as her drawings–the book is a potent information source about this interesting and important contemporary artist.

Peter Schjeldahl — in a 1998 catalog essay reprinted in the book — composes a marvelous piece of exclamatory writing that manages the task with only one exclamation point! He talks about The Kitchen as “ungraspable in its wholeness, like the Mississippi river delta.” The writer touches all the major points about the artist’s works–that she’s unfraid of beauty; that she’s making theme park/spectacle art; that the work’s feminist; and that it’s public art. Schjeldahl actually volunteered to help Lou on her 1996 “Back Yard” (she used volunteers in this piece), calling himself “the creator of 21 of the finest blades” (of grass–there are 250,000 blades of grass in the installation).

Schjeldahl calls the early works “zany, polemical and extroverted” something that can’t be said for Lou’s more recent works, which are political not polemical, introverted and far from zany.

Eleanor Heartney, in an essay from 2011, details Lou’s biography, and contrasts Lou’s un-ironic and populist works with contemporary pop art makers, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst whose works come “laden with irony and a sense of social superiority.” On the other hand, Heartney puts Lou into the category of “endurance art,” a place where Marina Abramovic and Chris Burden subject their bodies to extreme conditions. While Lou doesn’t create her beaded works before an audience, the works are truly endurance art in their making. Photos throughout the book show the artist on hands and knees, or lying down on top of one of her pieces performing the intricate and painstaking beadwork, sometimes with glue and other times with thread.

Lou was awarded the MacArthur “genius” award in 2002 when she was 32 years old. In 2005 she began working in South Africa with expert Zulu bead workers. She was smitten by the country and by the workers and she up and moved there.

Lou’s had a spiritual journey as well as a geographical one. From her evangelical upbringing in Minnesota and California, through a Buddhist period and into a realm now of what feels like secular humanism.

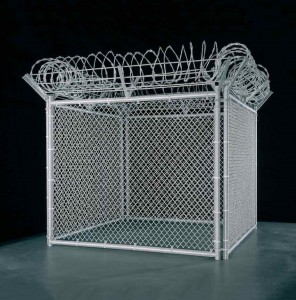

While the early art was irreverent, exuberant and proud of life’s humble pleasures, her works from the South Africa period are reverent, downbeat and in some cases preachy. Contrast the hot, cartoony flamboyance of “Kitchen” with the colorless prickly and argumentative “Security Fence” from 2005 and you have to say this is an artist who’s channeling her surroundings but has lost her sense of humor and her sense of wonder.

More recently, Lou is turning out minimalist pieces like “Continuous Mile” and “Endless Mile” that are the triumph of process over content, pure beading for beading’s sake.

The book is a terrific read, from Schjeldahl’s poetic romp to Heartney’s art historical exploration and Lawrence Weschler’s Q&A with the artist, which gets into her childhood and her cathartic performance piece, “Born Again,” a monolog about her upbringing. If you’re on the West Coast, Lou is having a show Mar. 26-May 7 at L&M Arts in Los Angeles.

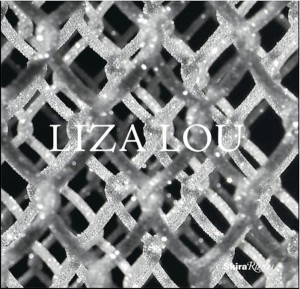

LIZA LOU

Texts by Eleanor Heartney, Lawrence Weschler, Arthur Lubow, and Peter Schjeldahl

Hardcover with jacket / 10” x 10” / 264 pages / 200 color photographs

$60.00 U.S., $69.00 Canadian, £39.95 UK

Skira Rizzoli / ISBN: 978-0-8478-3461-7

www.rizzoliusa.com