The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) is celebrating one of its most illustrious alumni with Henry Ossawa Tanner; Modern Spirit (through April 15, 2012) and it is greatly to be welcomed. While Tanner is well represented in PAFA’s collection and that of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA, which organized a Tanner exhibition in 1991), his work is widely dispersed in public and private collections in the U.S. and France, and the exhibition brings them together and into public view, many for the first time since they were acquired. A deep appreciation of Tanner will involve some work on the part of viewers, and will require them to set aside late 20th and 21st century taste and consider a subject that may be one of the few that we find truly unacceptable: religious faith.

Supporters of the avant garde have been willing to accept modern religious art in two forms only: when the spiritual is channeled through abstraction (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Rothko, Polke), or when expressed by artists working outside the official institutions of art (Gertrude Morgan, Howard Finster). Tanner received an academic art education, both at PAFA, then at the Academie Julien, Paris. While he produced work across genres (some portraits, a few genre scenes, many landscapes), his highest expression was in the form most valued by his training and by the mainstream art institutions of his day: history painting. In Tanner’s case this meant scenes from the Hebrew and Christian Bible. Tanner’s son described him as a mystic, but Tanner’s faith was likely consistent with that of his father, a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This distinguished him from the occult mysticism of his period promoted by figures such as Madame Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner (whose influence on abstract art was significant).

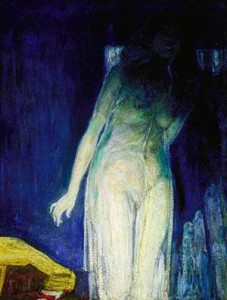

The exhibition situates Tanner as a modern spirit, which is true if one considers him a man of his times. But a modernist he was not. The winners in art history (as told until now) have been the artists who rejected the tenets of academic art, yet Tanner and most of his contemporaries retained traditional values about art, even as they enjoyed technical advances in paints, lighting, transportation and everyday life. A number chose religious subjects, as did occasional modernists. Around the year 1900, William Trubler, Jean Benner and Louis Corinth each depicted Salome (a subject, admittedly, appreciated more for its sexual than its religious aspect, at the fin de siecle), and painters of Christian subjects included a broad range of artists, among them Eugene Carriere, William-Adolphe Bougereau, Maurice Denis, Edward Munch and Pablo Picasso, who showed mourners in a chapel in The Burial of Casagemas (Evocation), 1901 (he, too, had an academic art education).

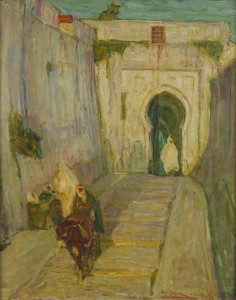

An African- American artist and son of a former slave who achieved an international reputation in late nineteenth-century Paris will inevitably be of interest for biographical and historical reasons, and the exhibition does a good job of situating Tanner within the racial context of his times. But Tanner always insisted that he wanted to be thought of as an artist, with no qualifier as to race. And it is the paintings that interest me. The exhibition’s labels are of little help in situating Tanner artistically; it doesn’t help that those in several of the rooms are almost illegible, printed in brown on a mole-grey background.

I left the exhibition with more questions than answers. Tanner spent most of his professional life in Paris, then the center of the art world. He would have seen a great deal of current art as well as that of the old masters. His early landscapes suggest a range of influences: his teacher, Eakins, Barbizon painting, the Hudson River school. The exhibition acknowledges the influence of Whistler on his later landscapes, but the paintings have similarities with the work of a number of artists familiar with French modernism but working on its periphery: Ferdinand Hodler, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Ferdinand Keller and others. Tanner’s Raising of Lazarus owes an obvious debt to Rembrandt, but what other painters made an impression on him? Letters survive, and it is likely he mentioned some of the paintings he studied.

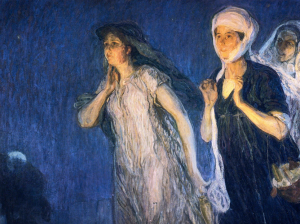

Tanner’s mature technique was experimental and distinctive, but while the curators suggest this as a modern aspect of his work, it is consistent with a number of artists during the 19th Century. He applied many layers of paints bound both in oil and temperas, some with additions of varnish. The choice of tempera usually indicates that the artist is interested in old master technique, although some artists were exposed to tempera paints used for theater sets. Artists from Joshua Reynolds on hoped to discover the secrets of the old masters, and the mid-nineteenth century saw the translation and publication of a number of early artist’s recipe books. Some of Tanner’s experiments produced problematic results; the deeply-cracked surface (alligatoring, as it is called) of the wonderful Salome ca. (1900) is a product of improper paint layering, ignoring the painters’ rule of fat over lean paint. But many of the later paintings have wonderful, if inscrutable, surfaces.

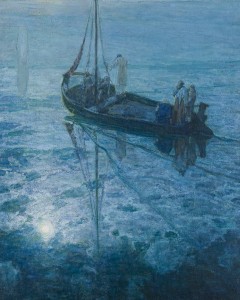

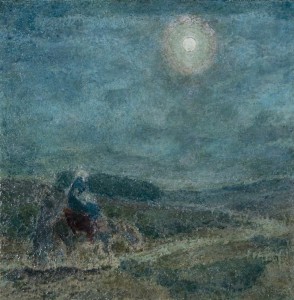

The most unusual aspect of Tanner’s work has received no significant discussion that I know of: his palette, most specifically his tendency to emphasize tones of blue, particularly in religious scenes; some are so exclusively blue that the paintings could be considered monochromes. Some are set in the evening, and blue is commonly associated with twilight; indeed, the French use the term l’heure bleu. But not all of Tanner’s blue paintings are obviously set at dusk or nighttime. The unnatural coloring certainly situates them beyond a realistic representation of observed visual effects. It also creates an affinity among a group of works that portray ordinary human activities performed in the presence of the divine. This highly personal and deeply felt recasting of religious imagery makes the most persuasive case for Tanner’s modernity.

The exhibition catalog, with 14 essays by French and American scholars, gives a much more nuanced picture of the artist than can be obtained from the exhibition itself. PAFA, by the way, is opening the exhibition free of charge on Sundays throughout the exhibition. That sends the clearest possible message about the broad audience they hope the exhibition will attract – and it should.