“My one regret in life is that I am not someone else.” – Woody Allen

Markus Hansen, the Paris-based German artist, is trying in more than a decade’s worth of projects to see what it might be like to be someone else, and then to confront that very notion of being someone else. Using a Felix the Cat bag o’ tricks to flesh out the narrative or even the feeling he’s someone else (you), one senses the tugging or nudging – imagine Peter Pan’s moment he lost his shadow – out of one’s singular identity. It’s a bit more than hearing your voice on an answering machine, and a bit less than an LSD trip. His work gives shape and form to the vagueness of sentiments like It’s hard to be you, I’m sure. Just as it’s hard to be me. Walk a mile in my shoes? Sorry, I don’t want the shirt off your back. You’re one in a million. You’re special. Unique. There will never be another you. I did it my way. I’ve got to be me…. Hansen’s inquiry, I sense, concerns the mechanics of the examined life.

Each Man Kills The Thing He loves. (Chambre Miroir) is the artist’s most recent and perhaps most precise expression of our dependency on seeing limited versions of ourselves reflected in someone else’s eyes – and of course our own. Located in the artist’s Paris studio, the “chambre” (room) is housed in its own modest white labyrinth. Constructed of plywood, a single, doorless entrance leads you and then leaves you with the choice of turning left or right, although neither direction seems to portend any advantage or disadvantage. It is, as Hansen suggests, an architectural palindrome with rippling internal palindromes: Eve damned Eden, mad Eve. Playing softly but consistently is the vaguely annoying song sung by Ingrid Caven from The Ballad of Reading Gaol (after Oscar Wilde).

One follows a short corridor cushioned throughout with a common, office-style grey carpet, and we are suddenly in a room with a view: A hi-fi with a pair of speakers, and a spinning turntable; several wires flare out of the back of the turn table and a mirror behind the unit reflects the back of the turntable and high-fi with its inputs and wires. Or does it? You stand in front and examine the machine and then, of course, your reflection (my reflection). The mirror is the sort you see in dressing rooms: Long and inexpensive, edged with metal and often fastened to a wall with clear plastic clamps or hooks. The reflection has a slightly grayish tint to it. One problem: When I stand in front it, I’m nowhere to be found.

What is so wonderful about this piece is the insistence of that the illusion we can see is really an illusion concerning ourselves, particularly how we grasp the past and manage the present. And it takes place in an instant and, as magic will have it, we need to dip into again. I imagine it like your first pot high when you find yourself in front of a mirror for what seems like the very first time.

The satisfying illusion harks back to the intimations of photography – the expectation of realism – that began, according to a controversial theory and book by David Hockney and a University of Arizona physicist Charles Falco (Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of Old Masters, 2001). The book proposes that many Renaissance painters didn’t come by their “perspective” through imagination but the vanishing point was conceived by use of lenses and mirrors. (See more here)

Mirrors and self-deception are the province of most artists, of course – illusionism in the package of Renaissance perspective (now no longer mined, interestingly enough) – and we perhaps delight most when we are fooled. Notably artists from da Vinci to Van Eyck to famously Hans Holbein to Manet on through to Escher and Michaelangelo Pistoletto and even Jeff Koons (think stainless steel balloon dog sculptures) continue to pack in the crowds. (And even impersonators play off the mirror image concept – check out Lorna Bliss impersonating Britney Spears in the barn burning “Idol” knock-off, Britain’s Got Talent).

Holbein The Younger’s The Ambassadors (at the National Gallery in London) resonates here because to fully understand that painting, one must approach it from about a 5-degree angle to see the skull in perspective – perhaps the key to the entire work – the rendezvous with death, the great equalizer and all that stuff. With Hansen’s Each Man Kills (Chambre Miroir), we are distracted by sound and shades of white (inside the labyrinth), and then encouraged to examine our presence and absence from multiple angles. An animated video on the artist’s website plays a bit with this idea, drawing in and pulling back, but it lacks the “realism” of the illusion.

Few works of art, in the end, are not “reflections” of some kind – whether sketches of skyscrapers in a puddle, or our tormented inner worlds in globs of paint on canvas. As sentient beings, we seek to situate not just others but ourselves, and the reason might be simple: It is virtually impossible to see our whole beings in a mirror. What we get, even with multiple mirrors is a fragment. Only the other can see us fully, and yet we often say, they can’t see us at all.

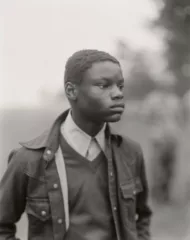

I should also note a project Hansen launched in 2004 (and still ongoing)– Other People’s Feelings. Here, in side by side portraits, the artist positions himself in relatively similar dress and more specifically similar facial gestures, with the idea to capture, in a flash, the mirror image of someone’s feelings, someone’s look. Subjectivity is truth, here, even as we objectively scour the image for “likeness” and incongruity. The examined life is indeed still worth living.