Paris is awash with counter cultural pen and ink these days. Long the home of the bande dessinée (comic strip), the City has recently succumbed to the vaguely psychotic allure of one of the country’s adopted misfits: Robert Crumb. Crumb, who lives in the south of France, hit the capital with a one-man all-out visual assault of desperate men and thick-thighed women at The Musée d’Art Moderne. Visiting British cartoonist Elliot Elam dropped into town to see the big show, but also to meet another of his cartooning idols, Gilbert Shelton.

Shelton, who lives in Paris, is best known for The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers (1968), and its spin-off strip, Fat Freddy’s Cat (1969). Much like Crumb, his most famous work takes a cynical look America’s moral and cultural aspirations, minding each faltering attempt with a cartoon army of hippies, dropouts and verbose felines.

Inspired by the likes of Shelton, Elam spent much of his youth photocopying his own small press comics in the north of England, and has dipped in and out of the scene ever since. Right now, he’s putting the finishing touches to a collected book of on-the-hoof sketches, inspired by people on the London Underground.

I talked to Elliot a bit about his book, his meeting with Shelton and his take on Crumb.

“I’m sure it’s the same on the Paris metro, but the Tube’s a funny place,” he says. “It’s full of this revolving cast of characters that shifts and slides as you travel from place to place. You’ve got the vinyl-haired moneyed women as you head West, for example, or the hip young things in the East, all dressed up in their ironic fashions and the retro shoes they bought on eBay.

“And all, for the most part, are off in their own little world. Nobody’s talking to anyone else. Instead, they’re all staring into the middle distance, or at some ‘app’ or other on their phone. I just figured that, if I was going to be down there so often, I might as well make use of that time and start drawing my fellow passengers. You see the occasional crazy, of course, but even the most boring become interesting when you look closely.”

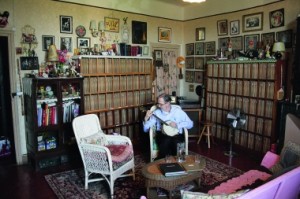

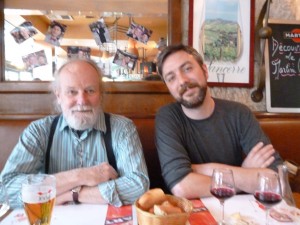

Elam got to show Gilbert Shelton some of these drawings when he visited the latter’s tiny studio over near the Bastille. ‘I’ve been a fan of Gilbert’s since my early teens’, says Elam, ‘Like most, I came to his comics for their drug-taking thrills and spills but stayed because they were so, so funny. So when, in his soft Texan accent, he said that he liked my drawings it made my week’.

It didn’t take long for Elam repay the compliment. ‘He showed me a new strip he was working on and immediately I was telling him how great it was. The panels were only half – or even a quarter – finished, but man, what a treat. I asked how long it took to finish a page and Gilbert laughed and sighed and said ‘forever.’ That was encouraging to hear, especially for a slacker like me. But seeing how he’d packed joke after joke into his drawings made me wonder about how funny my own work was, and I resolved to scratch my subjects and situations a little more, so I could milk more of the humor from them.”

One of the ways Shelton speeds up his output is by collaborating with others. For a decade or so now he’s been working with the French comic artist Pic on a set of stories about a terrible rock band called ‘Not Quite Dead’. In the past, he’s worked also closely with Paul Mavrides, the San Francisco-based artist behind the look and feel of the cult parody religion, Church of the Subgenius.

“Gilbert told me a great story about how he and Mavrides got flown to Amsterdam by High Times magazine,” says Elam. “They were to be judges for a marijuana seed grower’s contest. On arrival, they were handed 30 samples of marijuana to smoke in five days: Mavrides wrote a detailed critique of everything, like an expert wine snob. But by the time Gilbert had smoked three puffs of the first one he was so stoned that he couldn’t differentiate one from the other, and so he just gave everything the same score.”

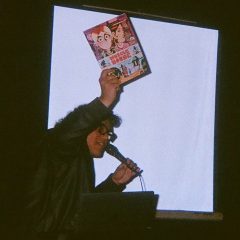

When he and Shelton were working in the Underground Comix scene of the 1960’s, Robert Crumb’s drug of choice was LSD. It kicked opened a seal in his brain and out poured the perverse, explicit sea of cartooning that made his name; adolescent sexual fantasies; wise-cracking gurus; rampant bird faced women. All are in among the 700 or so works that fill La Musée Moderne through August 19, in a vast retrospective of Crumb’s career.