From city streets to country highways, neon signs are a part of our commercial landscape. Or, as Len Davidson, former sociology professor, neon fabricator, collector and advocate puts it, neon is part of our “roadside culture.”

Operating beyond roadside culture, Davidson says, is another stream of neon. Artisans, tinkerers and fine artists, some of them sign makers by day, create this art, which is the subject of a new exhibition at The Philadelphia Center for Architecture (1218 Arch St.). “Neon Art: Folk, Found, Fine,” organized by Davidson, features thirteen local and national artists, including the late Val Maddalo, a tinkerer and sign maker.

Davidson, who runs the Davidson Neon business and created the Neon Art Museum to showcase his large collection, abandoned academe to apprentice with Jim Williams, a Florida master sign maker to learn the craft himself. The advocate is fiercely proud of neon art made by the old timers. “The tinkerers, they didn’t call it art” he said.

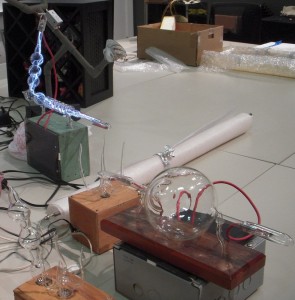

Davidson considers the folk art made by Maddalo and others on par with fine art. “It’s all the same thing in my mind. Even artists would say that,” he said. The work was made for friends and family and sprang from a pure artistic place, from a love of making things and a fascination with neon technology, which is a kind of magic light created when an inert gas like neon, argon, xenon is converted to colored light via electricity in a glass tube.

The show is a jumble of fine art and folk art, everything sitting companionably together. You won’t find any sales pitches here even though there are lots of words. Mostly, the word art is elliptical and either playful or ambiguous in meaning.

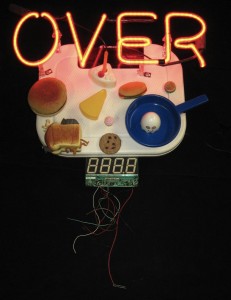

Maddalo and Davidson use found objects like toys and other flea market finds in their works. Their folk art pieces are sweet and homey and imbued with a nostalgic feel. Other works are closer to today’s fine art using abstract gestures and a more contemporary aesthetic, like the colored squiggles, swirls or geometric shapes of John Tanaka, or the expressive figuration of Eve Hoyt, the only woman in the show.

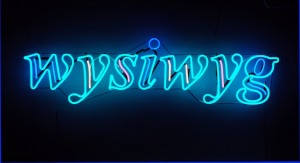

Zac Weinberg and Angus Powers’ piece uses one word – APPLAUSE – positioned atop utilitarian-looking stanchion. The deadpan work is sound-activated using clap on/clap off technology, and it evokes both the phony canned audience responses on tv sitcoms and the loneliness of stand up comedians looking for laughter and applause. Other word art like Jacob Fishman’s cyber-blue “wysiwyg” (what you see is what you get) and Annson Kenny’s “On the Line,” which resembles a diagrammed sentence fragment, feel right in tune with today’s word art.

Light-art pioneer Dan Flavin (1933-1996), who used colored fluorescent tubes in his important minimalist installations in the early 1960s, brought utilitarian lighting into the exalted realm of fine art. But his works seem less influential on these artists than the work of conceptual artist Bruce Nauman. Nauman, a master of cryptic deadpan language, made neon word pieces that parodied commercial signs and had oracular messages. His 1967 piece, “The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths,” a spiraling sign owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is an obvious precursor and influence on the work in this show. What makes Nauman influential is his use of words in ambiguous, elliptical ways…and the fact that his fine art pieces actually look like they could be commercial signs.

“Neon and architecture are synonymous,” said David Bender, the Center’s Coordinator, who pointed out that also on view are thirteen commercial neon signs on semi-permanent loan from Davidson’s Neon Museum. The signs, many of which are from Philadelphia (Pompeii Grille, Jim McGillin’s Old Ale House) have been up since 2008 when the Center opened. This is Davidson’s first neon exhibit at the Center but probably not the neon advocate’s last.

Neon Art: Folk, Found, Fine, to July 27. The Philadelphia Center for Architecture, 1218 Arch St.

This article ran in the Philadelphia Daily News June 8, as part of Art Attack, a partnership with Drexel University supported by a grant from the Knight/NEA Community Arts Journalism Challenge and administered by the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance.