Photo Book – Reframing Photography

Reframing Photography, the 560-page encyclopedic book on the subject includes everything about photography and then some. The book is for students, teachers and those in the self-taught orbit who want to do it themselves with a little help.

Like those instruction manuals that come with your new camera, the book is a little overwhelming — although unlike those barely-English manuals, this book is written! There are fabulous essays written by the two authors, Rebekah Modrak and Bill Anthes, in each of the four subject parts, and they live up to the encyclopedia: dense, with history, science, and an interweaving of anecdotes of present day usage that reverberate with photography’s past (my favorite is the comparison of Janet Cardiff’s audio or video walks with the idea of the camera obscura, which works pretty well I think — Cardiff does turn the world inside out and upside down, giving you her image, sounds, movement, which you must translate back into your own world to make sense of.)

The book has learned from the Internet’s way of doing business. The horizontal layout includes two “sidebar” columns on each page, one to show images referred to in the text and the other for footnotes, which are like what you might get online in a hyper-linked word — more useful information about the subject.

Reframing, like the encyclopedia or dictionary, is not a linear read. You want something about the how human vision works and what information about the eye and sight has meant for photography? There’s a comprehensive essay by Rebekah Modrak that covers all that. Maybe you want to jump right in to the “how to” chapters. There’s one on framing that deals with compositional issues. It will tell you how to make a pinhole camera, and steps you through the various cameras available and what they do. Other “how to” chapters deal with lighting, reproducing and printing and editing and evaluating.

Speaking of the Internet, the book has a large and very useful website with video tutorials with images and discussion from the book only not as dense. And one great segment online is author Modrak’s curated artist’s gallery, with short documentary films of young contemporary practitioners pushing the boundaries of art and photography talking about their work. (Among those featured are Artie Vierkant, a UPenn graduate, and Christobal Mendoza, who showed collaborative work recently at Grizzly Grizzly.)

One of the great things about the book — which took seven years to write — is its underlying premise — that everybody uses photography now, and that for some artists, photography is one, but not the only tool in their studio. The authors, artist Rebekah Modrak and art historian Bill Anthes, understand that the future of fine art photography might look considerably different than a simple show of framed works hung on a wall. And because of that open interpretation of the field, the book embraces every possible use of the tool and discusses it with open mind. There seem to be no biases here, just a lot of great facts rounded up and some smart thoughtful commentary — with lots of pictures.

Reframing Photography: Theory and Practice

By Rebekah Modrak, Bill Anthes

Routledge – 560 pages

ISBN 978-0-415-77920-3: $59.95

Photo Movie – William Eggleston in the Real World

With all the color photography in the world these days and with the recent Cindy Sherman’s retrospective at MoMA, I grabbed the documentary movie “William Eggleston in the Real World” (2005, watch trailer) from Netflix and fell into in the strange, Southern Gothic world inhabited by the father of modern color photography.

The 84-minute movie, written and directed by Michael Almereyda, opens with the photographer and his son Winston who are on a photo shoot. Eggleston has been commissioned by filmmaker Gus Van Sant to shoot photos in his hometown, Louisville, KY. The photographer seems taciturn and uncommunicative. When he does speak he mumbles (his words are subtitled). You follow him shooting with various cameras, looking at furniture and signs through store windows, at night and again during the day. He seems to wander aimlessly and then stop and shoot. The man was born in 1939 which would make him 65 years old about the time the movie was made (the movie came out in 2005). But his slump-shouldered bearing and shuffling gait are that of a much older man.

Eggleston, whose works focus on the mundane and celebrate the beauty of ordinary things is himself other than ordinary. He is a cypher. His conversations with people, portrayed in this fly on the wall documentary are largely one-sided. Mostly he listens and puts in an occasional grunted retort.

The movie’s ambiance matches Eggleston’s moodiness. It’s arty in the way it is shot. And it feels somewhat raw. Almereyda had great access to the artist and one scene of Eggleston and his wife, totally in their cups and speaking drunkenly, is hard to watch.

In a passage near the end the filmmaker tries to discuss with the artist the importance of his works, and Eggleston stubbornly adheres to the notion that pretty much what you see is what you get. Pictures are pictures and that’s it — don’t look for more. It’s a remarkable exchange and lands like a big question mark after seeing all of Eggleston’s works, which are so clearly thoughtful and more than just pictures. And of course, there is the fact that the artist was a pioneer of color photography. He may think his pictures are just pictures, but his mark on photography is huge, from his use of the dye transfer printing process, which gives his works an unprecedented color saturation, to his choice of subject. The small, the ordinary and the unsung needed a champion and Eggleston stepped up.

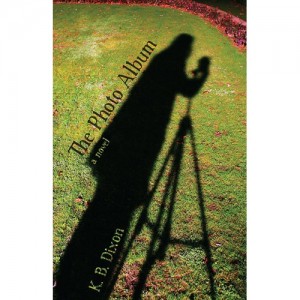

Photo Book – The Photo Album

The Photo Album by K.B. Dixon is a fictional memoir of a grumpy amateur photographer. Laid out like a photo scrap book with each page bringing a new photo and new caption — a sentence or an entire page — it’s a book of imagination that asks you to use yours. The first thing you need to imagine is all the photos, because there are none.

What appears at the top of each of the 120-plate pages is a small blank rectangle, mostly horizontally placed (landscape), with a couple verticals (portrait). The narrator refers to the photos as if you can see them but of course you can’t, which initially is funny, and then gets annoying, but finally, when all is said and done, is ok. Because while the story uses photography to tell us things about this nameless narrator, photography is an intellectualization, a theme, and the real business of the book is about the guy and his family, few friends and neighbors.

What appears at the top of each of the 120-plate pages is a small blank rectangle, mostly horizontally placed (landscape), with a couple verticals (portrait). The narrator refers to the photos as if you can see them but of course you can’t, which initially is funny, and then gets annoying, but finally, when all is said and done, is ok. Because while the story uses photography to tell us things about this nameless narrator, photography is an intellectualization, a theme, and the real business of the book is about the guy and his family, few friends and neighbors.

Our narrator is full of opinions. He is catty about other photographers; catty about neighbors and roughly dismissive. The musings seem like unedited obsessive thinking that you would never show your friends or even your family. Not for publication. Some people come in for particular bashing and scorn. It’s almost like the world of reality tv, where someone speaks a monolog to the camera dishing about the others, although not to their face, never to their face.

What you learn in this book is that the narrator had a difficult mother, is married to a beautiful and interesting woman, has a crazy daughter and a novelist friend. He roams the neighborhood taking pictures but doesn’t like street photography. He takes people photos but loves taking dark, abstract photos (a dark hallway, a microscopic corner of a park).

The writing is witty and the quips fall fast and furiously, like punchlines by Don Rickles. And along the way, our narrator lays some big ones on the art world too. He says photography is a diversion when you don’t want to deal with something else. Photography is a peripheral art — like dance. Is photography art at all? Whatever, it doesn’t matter. He muses that his desire to take beautiful photos makes him bourgeois. And while painting is harder than photography making photography the refuge of those who can’t paint, thinking about painting is easier than thinking about photography.

When he’s not waxing on about photography, this neurotic narrator zeroes in obsessively on his neighbors. Let’s not say he’s stalking them, but he is fascinated or annoyed. Fascination comes in with one family whose 16 year old son has gone missing. Pictures of the family members and the boy’s girlfriends come up again and again as a way of musing about what happened to the kid and the family. Annoyance is all over another family, especially with the mother who, he says, is an alcoholic, and who he says, had an affair with a contractor. He particularly beats on this woman (in fact a lot of the women in the book come in for more than their share of criticism). His own daughter comes in for some harsh scrutiny as she breaks up with a boyfriend and takes on a puppy, who becomes a child surrogate (at one point we are told the daughter is teaching the dog to read).

To be fair, the guy is hard on himself, too. He knows he’s depressed, and that he’s hard to live with. He doesn’t know how his wife puts up with him. But he can’t make himself go get some help. He has photographed the hallway leading to the doctor’s office, but he can’t go through the door.

I had just finished reading this book when I read Roberto Bolano’s short story Labyrinth in the New Yorker (Read it here — thank you, New Yorker!). Here was a story that had the same architecture as Dixon’s Photo Album — only Bolano gave you the picture. Again, you have a narrator talking about a photo. This photo is of eight people sitting at a table in a cafe. The narrator introduces the characters and talks about who’s cheating on whom with whom, but then the story goes off on a surreal interiorized journey like only Bolano can write.

Bolano’s story like Dixon’s book, uses photography as a framework for telling a tale. Both authors are obsessive and obsessed with people and human relationships. The idea in both works, of someone watching you, observing closely and speculating about your motives, your life, is one that is at base a little haunting, and chilling. We all have catty thoughts about others, and we are astute watchers. We have jealousies and secret obsessions like these narrators. But we don’t all write down or share our observations, because, well, for one, we’re too busy. Bolano and Dixon give you a time out from busy and from being good. It’s a guilty pleasure to watch the watcher and read his or her thoughts.

The Photo Album

by K.B. Dixon

Inkwater Press

ISBN: 9781592997022

Pages: 134

Price: $15.95