When he took over as Director and CEO of Woodmere Art Museum, one of the first things William Valerio did was rip up the shabby carpeting in the museum’s signature, high-ceilinged Catherine Kuch Gallery. The plan was to replace the carpet, but Valerio took one look at the beautiful concrete floor and decided that with a little spit and polish, concrete was the way to go.

A switch from carpet to concrete may not seem a radical move. But for Woodmere, a quiet museum in Chestnut Hill without a lot of foot traffic and a reputation somewhat marginalized by the other, bigger museums in town, it signaled a desire to enter the 21st-century museum world and become a player.

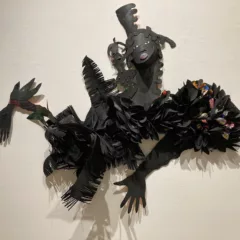

With one stroke, Woodmere announced that it “got it,” that it understood that contemporary art — large paintings and sculpture, bold abstractions with stripped down aesthetic — looks bad on carpeting. It would now have a floor that ranks with those of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Institute of Contemporary Art.

Woodmere opened as a public art museum in 1940, founded by Charles Knox Smith, who gave his art collection and the 19th-century stone Victorian mansion home to the public. Knox was a self-made millionaire who grew up poor in Philadelphia but felt the need to give back when he could. He collected art and was committed to connecting the Philadelphia public with it.

Valerio arrived in September 2010 after being recruited by the board. “The job had been to reinvent museum. It had been sleepy for some time and the previous director and curator had been gone for two years. The board was looking for new direction forward.”

What they wanted was a museum that would celebrate the local arts community. “They said, we really believe we need a museum dedicated to Philadelphia artists and we need someone to bring it to life,” Valerio said.

From changes to infrastructure and programming to reorganizing the annual juried exhibition, that’s what the director is doing.

Last year he replaced the 1987 HVAC system, which was not quite strong enough to cool the galleries. He installed a pitched roof to replace the problematic flat one that had a water pooling problem, and a water drainage system. He replaced single pane windows with double pane. All these deferred maintenance upgrades helped bring the 19th-century building up to today’s standards for art museums. Now he is busy with a project to restore the historic tin-ceilinged galleries, designed with Thomas Edison’s light bulbs in mind.

“The museum building is very important in framing the art,” said Valerio, an art historian and former assistant director of administration at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. But so is programming, something Woodmere didn’t understand before, according to Valerio. “Programming becomes a platform for people to come to the museum,” he said.

“I believe museums are social places. People come with their kids, their families,” he said. “Fifty years ago people went alone for an existential experience. That’s over.”

Woodmere now has a regular Friday night jazz program and a Sunday afternoon classical concert series, and, as the director points out, those attract two different audiences. For family programming, the museum now partners with its neighbor, the Morris Arboretum, on efforts such as joint ticketing. “Attendance is up, in a terrific way,” he said.

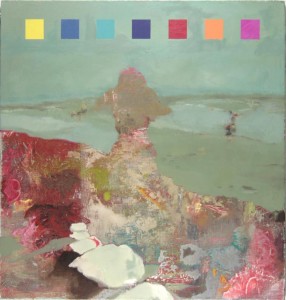

Four exhibits open tonight at Woodmere. All four are examples of the museum pursuing its dream of telling the story of Philadelphia art and artists: The 71st annual juried show; a solo exhibit by Philadelphia painter Alex Kanevsky (who also juried the annual show); a collection show selected by Kanevsky; and a solo show of works by local artist Doris Staffel.

This is the first annual juried show selected by a local artist and not by a curator or academic or a group. Russian-born and Philadelphia-educated, Kanevsky teaches at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and is a widely-respected artist.

The museum also wanted Kanevsky to exhibit his own work at the same time, and to pull together a show from the museum’s collection of 3,000 objects that would complement and give historical context for the juried exhibit.

“I wasn’t sure it was my cup of tea,” Kanevsky said. But he felt he could do some good by making a beautiful show.

“It’s a big city, with a lot of interesting art, and this is sorely needed,” he said.

Interestingly, Kanevsky, who has been a Philadelphia artist for many years, has never showed his work before at Woodmere. He had only ever been to Woodmere once. “It was never a destination for me in the past,” he said.

From 450 submissions, Kanevsky picked work by 46 Philadelphia artists.

A peek at the show’s catalog reveals a lot of traditional Philadelphia painting — figurative works (even a nude), urban landscapes, and abstraction, which Kanevsky characterized as “School of Philadelphia” abstraction, with “that sense of something straightforward and at the same time kind of crazy — like Philadelphia itself.” The show doesn’t tell the whole story of today’s art in Philadelphia, but it tells a slice of the story, and Woodmere will deliver other slices in future years.

“The art of our city is world class, and Woodmere can be a champion of that and tell the story,” said Valerio.

This story appeared in Philadelphia Daily News Aug. 3, 2012, as part of Art Attack, a project between the newspaper and Drexel University administered by the Philadelphia Cultural Alliance and funded by the Knight Foundation.