My companion and I were so giddy after a great day at the 5th Annual Governor’s Island Art Fair that when Homeland Security officers pulled us over in Lower Manhattan and began searching the truck for “radioactive devices that could be used to detonate a nuclear bomb,” we really didn’t care, and kept on gabbing about all we had seen.

At GIAF I talked to a broad range of emerging and established artists and saw fresh ideas they were still tinkering with. I found the curation scant on conceptual but evenly representative of installation, video, painting, sculpture and light art. Set in the worn and decaying residences of a four-story barracks, the exhibition unfolds as one big, burgeoning, site-specific installation.

Each year approximately 120 artists are chosen to participate. They are given a room and the freedom to curate their own work with the added luxury of not paying any fees. GIAF is run by 4heads, the New York-based artists Nicole Laemmie, Jack Robinson, Ernie Sandidge, and Antony Zito. With the support of volunteers and donors, 4heads juggles curation, administration, event planning, and public relations.

Meanwhile, through the summer, 12 artists culled from the Art Students League and from the ranks of past GIAF shows, worked in free studios on the island from June 12 until opening day September 1. All 12 are included in the Fair.

My wallet appreciated the free admission and the free, scenic ferry ride to Governor’s Island from the beautiful Beaux-Arts Battery Maritime Building in Manhattan. (batterymaritimebuilding.com) I enjoyed the stroll over to Building 12, and pictured the island’s Army and Coast Guard years, before the island was decommissioned. Today, The Trust of Governor’s Island manages 150 acres of public and park spaces for the people of New York.

The setting was messy, sweaty, hard-working–the opposite of the sterility you often find at commercial art fairs. I was comfortable the moment I arrived and hoped I could see everything. As I entered the first building, I heard someone calling for a hammer and then an artist came up and said, “Can I tell you about my work?”

Childhood and innocence are recurring themes at this year’s fair. For me, the highlight was watching Matthew A. Handal’s video “Riding with dissABILITIES,” that documents a disabled boy’s enthusiasm for riding horses. Mr. Handal strikes the perfect tone, neither cool nor sappy, and supports his story with great framing and editing. He was included in the GIAF through the New York Foundation for the Arts’ The Artist As Entrepreneur: Boot Camp program.

Rooted in childlike fantasy or the sophistication of today’s children who mature so early, Lisa Barnstone and Tricia McLaughlin have made “Lexington Line,” a video subway ride that starts with realistic footage, then changes into stop-motion puppetry and graphic animated film. After pink smoke covers the train, a cartoon vacuum goes through the motion of cleaning the video footage itself. A shadow cast by the vacuum wand places it’s action above another drama: a strange bug with an old lady’s head, who is creeping around tree stumps. I like that Tricia and Lisa are layering apparently random subjects; yet the subjects relate well enough to create a child-like perspective, possibly describing a child puzzling out old age.

Also exploring the childhood theme, Tine Kindermann (her surnames means literally children-man) mixes innocence and evil. She makes her own Hummel figurines that recreate Nazi scenarios, effectively expressing innocence bowing to the pressure of self-preservation. For this exhibition she showed superbly made peephole installations of childhood memories. The new work is lyrical and lighter in its story-telling.

Many GIAF artists expressed innocence from the adult perspective: they are not returning to childhood but pushing forward towards death and the unknown. Bernice Kramer‘s creepy, headless, upside-down, hanging papier maché figures droop with painful honesty and make me think of souls that have shed their bodies.

Building 12 enhances the sense of mortality and decay — with a frilly wallpaper border here, buckling floorboards there, and paint blistering off almost every surface, each room retains some clue of past inhabitants. Part of the Freeform group, Elizabeth Allison’s figurative sculpture “Turning Out” menaces the most bland, middle-class kitchen imaginable, under a ceiling of exquisitely peeling paint.

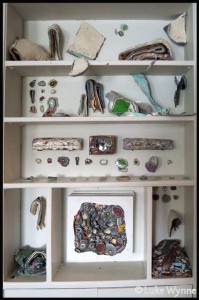

An artist who pushes materials past their limit and into decay, Nick Horman ponders DeLeuze, deconstruction, destruction, and la difference by carefully cataloging sushi-sliced layers of paint. (In case you’re wondering, he gouges chunks of layered paint from his own thick, multi-layered paintings, some of which are displayed nearby). The work is mildly violent and yet proper as a butterfly collection on a Victorian bookshelf.

For me, a pessimist, socially conscious work is at best a detour on the road from innocence to decay. Two installations here ask, Can we make the world a better place as we coast towards oblivion? And are the days of shrill protest over? By referring to our dead-end gas-guzzling culture, Elizabeth Keithline‘s wire motorcycle sculpture asks another question: What is strength? The motorcycle has spawned a baby that looks just like it: will there be enough oil for mother, child, and future generations? Keithline’s sculptures visualize the hope of a lighter environmental footprint.

Brent Felker knew the wall behind the empty shelves in his room would be the perfect surface for projecting video footage of interviews with Occupy Wall Street protesters. Silently combining these with a mirror that reflects the viewer and with a continuous loop of Walden Pond that alludes to natural peace and Thoreau’s writing, “Reflections on Civil Disobedience” shares my aversion for loud protest. (I later learned that Brent had the sound turned down to respect his neighboring artists, nevertheless, politeness is quiet.) He supports the movement but frames and domesticates it by bringing it indoors, possibly thinking of certain protesters who, like Thoreau, returned for home-baked cookies on Sunday.

Aside from looking at how the work at GIAF hangs and works together, I have to mention three artists who stood out and resist my thematic treatment. Emily Chatton‘s ink on mylar installation Summit was a gift of light, color and organic pattern. Visitors entered the room and stayed: the space felt alpine–cool, airy and restful. Adam Daily sought to make his spray-painted, vibrant geometric shapes on PVC even smoother; his reduction of texture de-emphasizes his personality and reminds me of Al Held’s paintings.

Finally, I had to laugh when I saw James Lentz‘s giant zipper on the floor. The 900-pound iron zipper prototype is built into a hardwood surround that matches the existing floor wood perfectly. Lentz says the sculpture alludes to “access and denial, protection, rebellion, secrecy, sex and social etiquette,” all subjects I associate with the art world in general.

I paused to imagine the zipper unzip and reveal the art a floor below, and the art below that, and then all the way back through the entire exhibit. This pause made me think about the Governor’s Island Art Fair as a whole, a place where artists are safe to expose new ideas, take risks and get artistically naked.

The exhibition is free and runs five weekends in September, each Saturday and Sunday 11-6.

Catch the free ferry from the Battery Maritime Building in Manhattan or the Fulton Ferry Landing in Brooklyn.