When I attended the curator’s talk at Franz Kline: Coal and Steel at the Allentown Art Museum (to Jan. 13, 2013), I noticed several Pennsylvania Power and Light (PPL) employees in the audience enjoying a cultural lunch hour. Their presence and PPL’s sustaining sponsorship of the museum make an appropriate backdrop for a regional reassessment of this major American artist, who, along with Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, is considered one of the top three Abstract Expressionists. Highlighting Kline’s childhood and attachment to the industrial Lehigh Valley, Coal and Steel unites Kline’s early realism with his late abstraction, framing the artist’s development within the beautiful but harsh environment we still experience today.

copyright 2012 The Franz Kline Estate Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1911, a year after Kline was born in Wilkes-Barre, PA, the Lehigh Valley Railroad was forced by the Supreme Court to divest itself of the coal companies it had held since 1868; it formed a separate company, the Lehigh Valley Coal Co. Nationally, railroads no longer controlled the production, contracts, and sales of their largest customer, the coal mining industry.

Living in the small coal town of Lehighton, PA, as a teenager, Kline would have witnessed the shift in the local economy as oil, gas, and hydroelectric generators began replacing coal, and modern businesses hired fewer and more specialized employees. In the exhibition catalogue, Dr. Robert S. Mattison, the show’s curator, writes: “In 1950, the year Kline was beginning his black-and-white canvases, [coal] production had dropped 80 percent. By 1940, three out of four miners were unemployed in the Pennsylvania towns surrounding Kline’s home.”

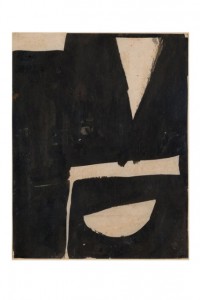

PPL efficiently transported and marketed electricity, setting up headquarters in Allentown in 1928; next door on the Lehigh River, Bethlehem Steel boomed during both world wars, making armor plate, ships, ordnance, and supplying bridge, high-rise and infrastructure projects. Mattison describes Kline’s late work as “megalithic and unstable, bold and explosive,” linking the artist’s power and ambition with the largest local businesses–energy and steel.

copyright 2012 THe Franz Kline Estate/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The early details of Kline’s life are of key importance to understanding his art. His father was either murdered or committed suicide and the artist was kept at Girard College, a school for orphaned boys, until he was fifteen, even after his mother was able to support him. His stepfather was a railroad engineer. Kline studied mechanical drawing and trained in a foundry workshop at Girard. He later excelled at cartooning while studying both at Heatherley’s School of Fine Art in London and with John Crosman, an important American illustrator.

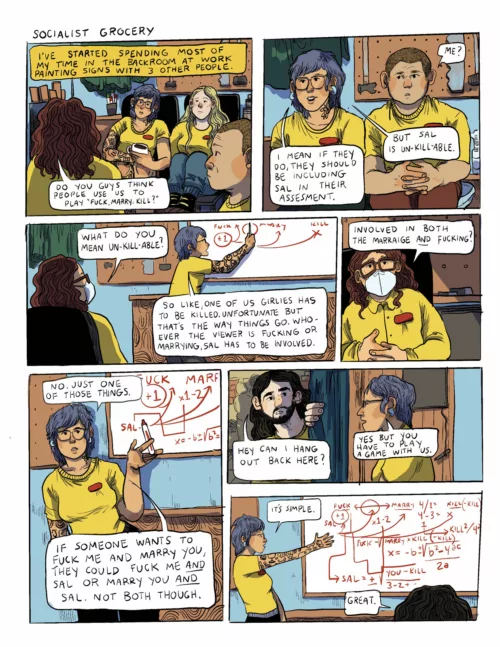

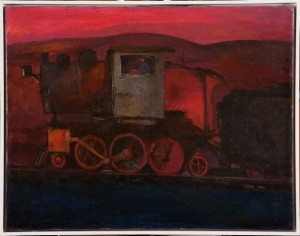

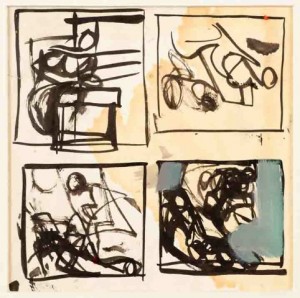

A sample of cartoons he made for his high school yearbook and newspaper are exhibited near photographs by Kline’s contemporary, George Harven, grounding Franz’s earliest art with documented scenes of coal mining: coal elevators, dusty miners, smoke stacks, coal cars and shacks. Kline’s early realistic drawings and paintings resist the then dominant American Romanticism and achieve a surprisingly cold effect by slathering trains and small-town buildings in muddy, sunset colors. In the 40s and 50s, after he had moved to New York, Kline memorialized dingy “patch towns” where miners lived, trains named “Black Diamond” and “Chief,” the railroad station in Jim Thorpe PA, the Lehighton-Weissport bridge, a bare Lehigh River, and the zinc-smelting polluted hills of Palmerton, PA, to name only a few. According to Mattison, Kline “returned home much more frequently than is commonly known…and talked constantly about his heritage in coal country” to his New York art world friends.

Orr Collection. copyright 2012 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York.

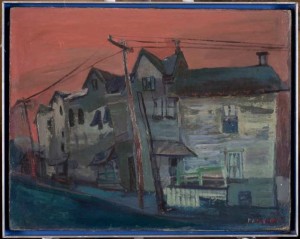

Several never-before or rarely-seen urban paintings that Kline made in New York following the Ashcan School and American Precisionist styles sparkle in the exhibition. In conjunction with the show, the Allentown Museum is showcasing a new acquisition, “Lower East Side Market (circa 1938),” which Kline made soon after he moved to New York.

Mattison connects this painting’s style with George Bellows, George Luks and John Sloan, and sees it as foretelling the structure of Kline’s later abstract art. Seeing “Lower East Side Market,” a lovely, prismatic urban scene made in the Ashcan style, together with “Chatham Square (circa 1948),” made in the Precisionist style, reveals Kline’s broad search for meaningful subject matter and a personal style.

Works such as “Street Scene Greenwich Village (1943),” “Studio Interior (1946),” and “71 West 3rd Street (1940)” synthesize a dark mood with lush painting, and focus our attention on a central window or bright square of paint. I get the sense of a sturdy center opposing the rest of the composition. Kline’s studio interiors featuring his wife, Elizabeth, or his favorite rocker, repeat organic curves contained within squares. Kline was considered restless, moving fourteen times during his twenty-four years in New York City. His wife was mentally ill, and he had to cope with this as well as his own contradictions: he was known as an assertive loner, a shy raconteur, and many have written about Kline’s abstract work as being an outward expression of internal emotional conflict. Overlaying Kline’s emotion with the dichotomy of Coal and Steel clarifies his development. I associate Coal, a resource for power and heat, with Kline’s inner drive, his need to express, his

emotional makeup; and I associate Steel, the secondary product, with his innovative art formed in response to failure, other contemporaries’ art and regional memories.

© 2012 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Seeing Franz Kline: Coal and Steel is especially powerful now that it’s winter and the trees are as bare as a late Kline’s brushstrokes, overlapping and locking your vision into tightening knots. “Turin (1960)” is a broken wheel, frozen but moving, and its raw black and white edges mesh to produce a silvery light. Exposed rock outcroppings on naked hillsides resemble the gestural L-C-and-V shapes that Kline frequently used. Now, I don’t picture New York City when I imagine Kline painting. I think of ravines, mine shafts, and a canal’s “reach” up river. Working in an out-sized scale, distilling internal and external forces, Kline’s achievement persists in a cold, harsh world.

Dr. Robert S. Mattison is the Marshall R. Metzgar Professor of Art History at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania.