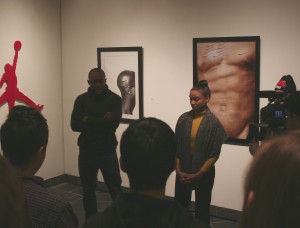

After winding through an unknown campus in a snowstorm, I walked into Haverford’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery and found the space packed with students, professors, and gallery assistants, bodies producing enough heat to do away with the furnace.

In the middle of the room, encircled by all of those bodies, eagerly engaging in a walk-through and public conversation about Other People’s Property, a survey of artist Hank Willis Thomas’ work, stood Thomas and curator Kalia Brooks, thinkers, collaborators and cousins. The conversation at this shows opening on Jan. 25 was a kinetic one, moving through the histories, concepts, and intentions – words trumping images, at least for that moment.

Thomas made his inspiration clear at the start: his cousin’s murder in 2000, a victim of robbery on Philadelphia’s streets. Struck by “all the lives ruined over the quest for commodity,” Thomas said he began exploring the black male body and its history of branding, identity, marking, and commerce. That exploration spiraled into a remarkable early career and hefty body of work.

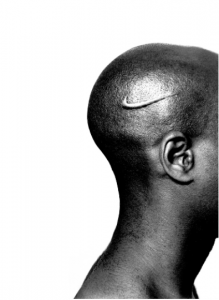

His research has him continuously diving into the origins of “blackness,” looking at statistical data, the history of slavery, and past and present advertisement campaigns. The concept of branding stood out to him most, struck by the layered relationship of literally branding slaves to mark ownership and contemporary athletic brands that symbolically co-opt the black male body. “I am still trying to negotiate and un-think this amazingly complex advertising campaign,” Thomas stated. Posing the question to the room, Thomas asked, “Is an ad ever really about the product?”

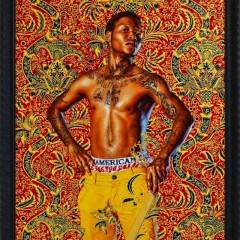

The first images in the space are from the Branded Series (2001-11) – perhaps the strongest in the show. Close-up photographs of the black male body echo Michael Jordan posters and Sports Illustrated spreads, highlighting definition, sleekness, and bone structure. (They should so clearly be erotic, but are anything but). Arrogance is conceptually subdued by the fact that these bodies are carved with Nike symbols, that definitive swoosh over the heart or on a shaved head – the placement symbolically pointing to the black male’s passion and intelligence as derivative of athleticism. Reference to scarification and popular culture, the past and the present, is reached with such precise simplicity, creating strong, powerful, and challenging statements at the gallery’s entrance.

Curation supported concept. The heavy black frames and shiny silvers spotting the space made it feel like a deconstructed Niketown, the presentation so crisp it almost felt stagnant. I didn’t like it – which was precisely the point. The athletic feel to the gallery became seamlessly integrated into the critique itself – taking these sleek, bold advertisement design tropes and applying it to the exhibition’s overall feel.

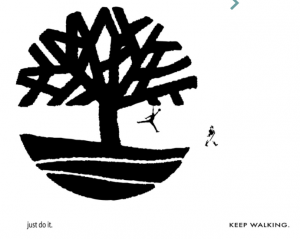

Thomas has an arresting ability to connect images and iconography of slave history with popular portrayals of black sports figures and their endorsements. Timberland and Jordan logos are merged into plantation landscapes and lynching narratives in a spookily easy manner in Thomas’ polished aluminum sculpture, Jordan and Johnny Walker in Timberland Circa 1923, 2009 and in the hauntingly poignant photograph Strange Fruit, 2011.

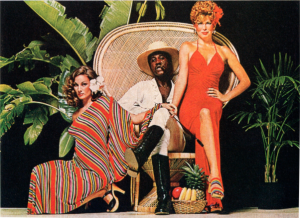

Another set of works re-presents printed advertisements. Thomas’ Are you the Right Kind of Woman for it? 1974/2007, depicts a black male seated on a rattan chair dressed in a safari-esque ensemble and flanked by two white women in bright red gowns. Palm trees and a basket full of tropical fruits compose the rest of the image. Speaking to the group, Thomas asked, “What do you think this advertisement was originally for?” Answers included cigars and Hawaii vacations, before someone correctly responded women’s fashion.

Re-co-opting the advertisements, Thomas is able to engage them as cultural artifacts and sites for deconstruction, thus, opening a discourse that would be otherwise hushed. The brilliance of Thomas’ works simply asks the viewer to look again, to re-imagine, and ultimately to critically analyze how popular culture has manipulated gender and race identities over time.

As much as Other People’s Property is a must-see, some criticism is warranted. With so much media before the opening, the works sometimes felt redundant and not special, almost if what was to be conveyed was already obtained before entering the gallery itself. This can often be a problem for photographers whose medium transfers online far better than painting or sculpture. The repetition of the pieces made them feel almost too obvious. After only a few images, you got it.

Nevertheless, Hank Willis Thomas’ images are necessary and powerful. The concepts, play of imagery, and overall critique are present and strong – huge statements delivered through subtle connotations and a delicate hand. His sense of history mixed with today’s popular culture becomes a homogenous narrative for the black male body – or at least one constructed view of the black male body. Thomas makes the complex connections and entangled histories seem effortless – boldly showing us what we inherently know, even if this inherent truth may be unacknowledged.

The show runs until March 8.