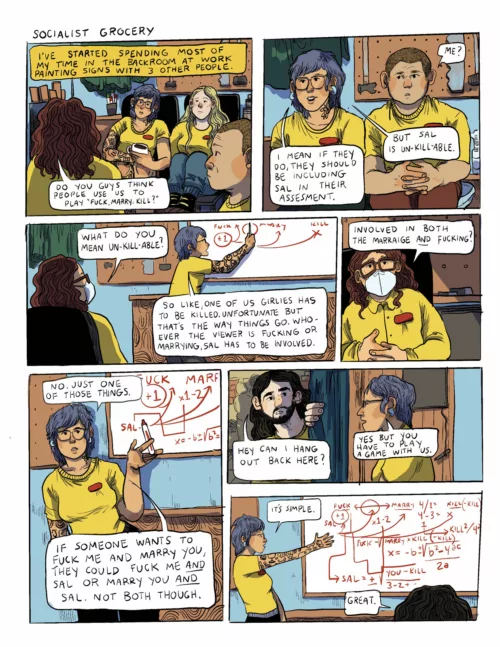

It’s hard to believe that the ever-youthful icon of the 1980s New York Artworld has already been gone 23 years. Keith Haring, the most famous subway scribbler the world has ever known, took chalk and markers and finally paint and canvas, and spread his scribbles across pretty much everything in his path. An expansive exhibition of his more political works – touching upon the state, media, capitalism, racism, nuclear and ecological suicide and finally AIDs – fills the Musée de la Ville de Paris to the brim, in an oddly joyful display of more than 100 large canvases, sculptures and collages.

Haring defined not only a certain spirit of New York in the 1980s, but also a very particular kind of mark: The line.

The Kutztown, PA native (1958-1990) drew in a simple cartoon fashion, creating a vocabulary almost overnight of his idiosyncratic hieroglyphics of crawling babies, barking dogs, “Everyman” figures (some with holes in them others brandishing crosses or getting zapped by spaceships), talking TVs, atomic bombs (with crawling babies) and a cavalry of monsters, penises, and angels. Immediately recognizable, Haring capitalized on the public’s consumption of his work by making politics, social muckraking and art his priority.

Haring had many styles, some more detailed than others.

In his Untitled, 25 September 1985, (top image) his palette is rich in color and echos pop artists Valerio Adami and Patrick Caulfield. This and other works like it raised the bar for street and graffiti artists with a sure hand and a fluid and graphic surrealism that takes on religion, television and the violence of excess.

The artist’s influence on others

His lines influenced almost every graffiti artist in the world, like Jean-Michel Basquiat, who drew crowns and mysterious texts in and around SoHo; Mark Kostabi who produced thousands of simple “everyman” line drawings during the same time period; and even the designer, Stephen Sprouse. Haring became a global brand, and indeed the artist traveled to Berlin before his death to add to the gallery of works painted on the Berlin Wall. Many of the works in the Paris exhibition were produced with friend and fellow graffiti artist LAII. Others echo a fashion that took hold of New York and other capitals and never let go – converse sneakers, pop shops, political art pasted up on walls everywhere. Vandalism? Well, those early 1980 subway posters could now buy you a house in Kutztown – or Paris.

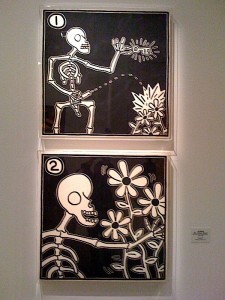

Keith Haring died of AIDs-related illnesses in February 1990, but he was perpetually concerned with death and acutely aware of the ravages a political and social oppression had on the world he lived in.

His take on drugs as well as the AIDs virus politicized through art a whole new way of political revolt. Silence = Death, a 1990 documentary by Rosa von Praunheim about AIDs and activism, featured Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, Alan Ginsburg among other artists, brought the political and the aesthetic into sharp focus.

What is key to the Haring legacy is public art – an art that was in the world, about repression of all stripes, and clear in its energetic poetry that the world could be changed with art, and with a single piece of chalk.

This is a wonderfully produced show and a pleasure to see the full breadth of Haring’s world – sculptures, objects (screens, an Egyptian sarcophagus, Coca-Cola signs and many drawn on vases and urns). The exhibition reminds anyone who saw his work as he created it or years later as it has spread across the planet like wildflowers that art does have a purpose. Haring’s work is particular in that it has a sincere and persistent joy. That joy persists in Paris through the end of summer. See it, it’s well worth the ride.

Keith Haring: The Political Line, April 19 – August 18, 2013. Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. 11, avenue du Président Wilson, 75016 Paris. Métro: Iena. For more information, hours and access: mam.paris.fr. Keith Haring Foundation/Information website.