Jonathon Keats has brought the cerebral into the art marketplace. Nearly 15 years ago he sat in a gallery for 24 hours looking at a nude model and selling his thoughts to art collectors. A few years later he copyrighted his mind as a sculpture. In 2004, he tried to genetically engineer God to get to the essence of the Divine. He’s enlisted string theory to purchase real estate in other dimensions, and created a silent four-minute and thirty-three second ring tone remixing John Cage’s composition 4’33” . And he even sold collectors the experience of spending money. Now in a new exhibit in Berlin he’s presenting a dozen of his “paintings” – made with mixtures of his own pheromones soaked in a linseed oil sauce – in order to get to the heart of Abstract Expressionism, artworks he accuses of being both passive and unsuccessful. In addition to his show in Berlin at Team Titanic, the artist has a project opening in New York June 11-14, and a new book “Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age.” I asked the provocative and art critical artist some questions recently.

Matthew Rose: We all experimented with art as children – what sort of child artist were you? What did you do with your finger paints and Crayolas?

Jonathon Keats: I was never especially interested in making art as a child, at least not by the means provided. Teachers made us finger paint in preschool and I hated it. I resisted instruction, not that I could have competently obeyed. Even when no one was telling me to be artistic, I pretty much ignored my magic markers and crayons.

I think I started making art without realizing it. (And keep in mind that I still don’t know whether what I’m doing is making art, nor do I really care.) When I was around six years old, I began selling rocks. I’d set up a table in front of my parents’ house in suburban Northern California and set some generic rocks on it, which I’d price to sell at a bargain one or two cents.

All around the table were other rocks left on the ground, essentially identical, that anybody could pick up for free if they wanted. Now I’ll admit that I didn’t have many customers, but still people preferred paying me.

I don’t think anyone ever took a rock from underfoot, or even asked about the distinction. Looking back — and probably totally over-thinking things — it seems to me that at the age of six I’d figured out the basic form of what I still do today. My street-side enterprise was absurd, but the absurdity of it let me explore the meaning of something society cares about very much with little understanding: money. I was naively experimenting with financial transactions. I’d instinctually stripped them of purpose so that I could see how they worked in the abstract.

At the time I obviously didn’t have the language to express any of this, but aside from that, I really haven’t progressed. I still refuse to follow instructions, and probably couldn’t paint or draw correctly if I tried. I still have no inclination to make art in the sense of creating objects for the sake of their aesthetics. Whatever you want to call my practice, I’m still working with only one motivation, which is curiosity, and with one technique, which is naiveté.

Forgeries as masterpieces

MR: You say forgeries in art are a good thing, in fact forgeries are the most performant art works. You say that artists, because they are in the business of anxiety, optimally force us to question our place on the planet, and even in our own minds. But the art enterprise has mostly failed to get our juices going. Forgers bring consciousness to a boil, and create a wealth of anxieties and questions about life, art, beauty and indeed, our existence – which is the purpose of art.

Your book Forged – Why Fakes Are The Great Art Of Our Age, says forgeries are the great art of our age. Do you mean contemporary works that are forged? Banksy’s stenciled graffiti works are often the subject of forgery. What about Hirst and Koons and other living artists? Isn’t it harder to forge living artists works? Maybe forgers could be content by forging signatures?

Forgery in art is the opposite of plagiarism, you say. Instead of passing off other people’s work as one’s own, forgers attempt to pass off their own work as someone else’s. The art world strategy of appropriation in the 1980s (Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, Mike Bidlo) turned this notion a few degrees by “re-presenting” work and questioning originality, ownership, creativity and art market value.

Jonathan Keats: Their [forgeries’] real art is to con us into accepting the works as authentic. They do so, inevitably, by finding our blind spots, and by exploiting our common-sense assumptions.(From an interview about the book.)

The artist and author contends that forged works force us to confront the flaws in our everyday perceptions and conventional beliefs, and that forgers are making some of the best art works.

Jonathon Keats: If you look at any avant-garde since the mid-19th century, you’ll see the worthiest artists are trying to rile society. From Edvard Munch’s Scream to Andy Warhol’s soup cans, modern art is a provocation, goading us to question our belief in everything from the marketplace to our own sanity. Yet the provocation is limited by the passive form art takes when it’s merely an image or object to be seen behind glass in an air-conditioned museum.

Forgeries in contrast are dangerous for everyone involved, regardless of the period or the quality of the art that’s faked. If museum art is housebroken, forgeries are feral.

To successfully pull off a con, a forger must have a keen sense of how we think. Forgers prey on our unjustified assumptions and our false beliefs. Sometimes they operate at an individual level. For example, a forger might take advantage of experts’ overconfidence. Other times forgers work on a societal level. For instance, a forger might exploit our unquestioning respect for institutional authority by tampering with archives. In one way or another, forgers shadow our blind spots, and when they get caught if they get caught), we’re forced to confront the flaws in our everyday perceptions and conventional beliefs.

The scandal provokes us to reexamine our worldview — which is exactly what good art strives to do. For that reason, I believe that the scandal deserves to be taken seriously as an artwork. A great scandal is a masterpiece.

The essential difference between legitimate art and forgery is that we can choose whether to look at a painting, whereas a forgery confronts us against our will. Even if you’re not personally defrauded, and even if you aren’t interested in art, you’ll hear about the scandal on television or read about it in the newspaper, and it’ll probably make you a little bit anxious. You’ll almost involuntarily ask whether you could have been duped, and in the process you’ll experience the most constructive effect of art, which is to understand yourself and your world more clearly. That’s why I believe that great forgeries are the most powerful and universal artworks produced by our society.

What’s the value of originality?

MR: Originality and value lie at the heart of your work. What is the true value of the original in these baroque and digital times?

Jonathon Keats: To me there’s no inherent value in an original, but there is immeasurable value in originality – or independent thinking – and if the exercise of an original idea requires the production of an “original” (or the creation of distinctions between ‘original’ and ‘copy’), then making originals (or copies) is a valuable activity.

In our society, the artistic concept of an original is related to the idea of authenticity as well as the notion of individual genius. In the first case, it’s equivalent to an original document. In the second, it’s related to authorship. Both senses of originality – authenticity and authorship – were explored by Duchamp and (less interestingly) by Sherrie Levine. But I don’t think that art has to be so narrowly artistic to examine these phenomena, because both phenomena resonate well beyond the art world. In my opinion, the work of the artists Shiho Fukuhara and Georg Tremmel is far more interesting than Levine’s brass urinal.

In 1992, the Australian company Florigene patented a sequence of petunia DNA that could be implanted in carnations and roses to make them blue. These genetically modified organisms (GMOs) were greenhouse-cloned and sold to florists pre-cut, ensuring that the Florigene holding company Suntory was the only source of the vastly popular flowers for nearly two decades. Then in 2009 Fukuhara and Tremmel tested the premises of this scientific monopoly. They reverse-engineered the plants, and released blue carnation seed into the wild.

As Fukuhara explained on the artists’ website, they were giving the plants a “chance of sexual reproduction” denied to them by Suntory. Living this wild new life, the flowers infringed on Suntory’s intellectual property by making countless unauthorized copies of their patented DNA. The pirated flowers became pirates in their own right just by attempting to live a natural life. Non-modified carnations were potentially also implicated by cross-pollination. The intellectual property protection of life – and the notions of originality inherent in intellectual property – were put to the test by the disobedience of flowers.

The value of forging Damien Hirst’s work

MR: What contemporary artists do you think are ripe for ripping off? Banksy? Koons? Hirst?

Jonathon Keats: If you’re asking which of these artists could be profitably forged, I suppose that all of them could be, since all have immense market value and cultural influence. And in the sense I described above – in my response to your second question – the forgery of any of these three artists could easily result in a scandal that might be a greater artwork than the work that’s been faked.

If you’re asking which artists’ ideas could be productively appropriated, I think that Damien Hirst offers some interesting opportunities. His most significant work comes from early in his career, and was never much pursued by him after he became famous. For instance consider his 1990 vitrine containing the maggot-infested head of a slaughtered cow and an insect-o-cutor that kills the flies nourished on the decaying flesh. The work is remarkable because it delves into the familiar artistic territory of the memento mori without succumbing to traditional artistic strategies.

Much of the history of art is the history of visual metaphor, in which abstract ideas are symbolically explored in concrete imagery. Hirst doesn’t provide that comforting detachment. His early transpositions are from one messy reality to another that proves equally messy. The lifecycle of those flies explains nothing about what it means to live and die. They take an enigma at the back of your mind and place it in front of you. They make the incomprehensible palpable. But as the market took him up, Hirst largely lost his touch. His medicine cabinets – with portentous names like ‘God’ – are a regression into symbolism, as is the famous diamond-encrusted cranium. His earlier way of working still has immense potential. Since he isn’t going to exploit it, others might as well.

Experimental philosophy and naivete

MR: What sorts of thinkers have fueled your interest in “cloning” the likes of Lady Gaga, Obama or any other famous person? Are you interested in evolutionary biologists like Richard Dawkins or language philosophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein, or even the deconstructionists like Jacques Derrida or perhaps Gilles Deluze, whose main interests seem to be identity and difference?

Jonathon Keats: I studied philosophy in school, and though I thoroughly enjoyed Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, I have serious reservations about the discipline as a whole. The questions pursued in academia are highly abstract and exceedingly narrow, and the audience for them is minuscule.

Before my studies began, I naively believed that philosophy would be a broader conversation encompassing everything and engaging everyone. When it didn’t turn out to be that way, I decided to drop the academic study of philosophy and to pursue my naiveté.

That’s what I’ve been doing ever since. I call myself an experimental philosopher not to be pretentious but because that’s the best job description. My projects are thought experiments, except that they aren’t written up as hypotheticals in scholarly journals. They’re designed to be experienced. Anybody can encounter them, interacting with the hypothetical and discussing the implications. I want to emphasize here that I don’t have any fixed ideas. There’s nothing I’m trying to demonstrate or prove. Unlike the thought experiments in academic journals, mine are truly experimental, and the results inform further experiments. It’s a positive feedback loop. The questions keep developing. In a sense this is a technique for bootstrapping curiosity.

So I wouldn’t say that any ‘thinkers’ have fueled my interest in cloning. I’m not working from or toward an academic theory. Rather what I’ve done is to take up the latest scientific research in epigenetics and apply it as rigorously as possible to current cultural obsessions that anybody might observe in the popular media. My thought experiment goes both ways. I’m interested in exploring the scientific assumptions of genetics while also examining mechanisms of celebrity and how we think about our past.

Cloning Lady Gaga and Jesus Christ

However there’s a danger in front-loading these explorations with my own explanations, which are no more worthy than anybody else’s. Better for me to concentrate on epigenetically cloning Lady Gaga and Jesus Christ – a process that may sound complex but is actually quite simple since it avoids the antiquated genetic concepts that have dogged would-be cloners in the past.

In recent years biologists have learned that the genes you inherit do not determine who you become. What matters is which genes are expressed, and gene expression depends on your environment. Epigenetics takes into account environmental factors including diet, stress, and exposure to toxins.

The idea behind epigenetic cloning ts to evaluate these factors and replicate them. So in the case of Lady Gaga or Jesus Christ, I begin by assessing their gross biochemical intake as reported in leading gossip magazines or books like the Bible. Then I administer these chemicals in purified form to people who want to become their clones. The easiest way to grasp the technique is to think of twins. As they age, identical twins diverge in appearance due to epigenetic drift. I’m doing the opposite, compelling genetically distinct people to converge by applying intense epigenetic force.

Emotional paintings made with pheremones

MR: Your newest works – the pheromone soup paintings that rescale the Abstract Expressionists’ cultural ranges – tug at our sensibilities while at the same time appearing to be consistent with the kind of self-consciousness art-making has concerned itself with during the past few decades. Does size matter with these new AbEx works? Can they be put in bottles? Or atomizers or spritzers? Is Dior a potential candidate to pick up your formula for a new AbEx scent? Jackson Pollock: Feel The Passion … But Drive Carefully…

Jonathon Keats: Art history certainly informed these works, but I certainly don’t mean for these paintings to be thought of as an insider critique a la Sherrie Levine. My purpose is to see what art can achieve that hasn’t yet been attempted.

Just think about it. Abstract Expressionism is now over half a century old, and yet emotive art is still dominated by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. If you want to express your feelings, the preferred technique is still to spill or spread colorful pigments onto a swathe of canvas. Through some sort of synesthetic transference, the artist’s tormented mindset is supposed to be experienced by the audience.

But to me it seems that there’s a more direct way to paint emotions: All you have to do is to paint with pheromones.

Pheromones have provided a way to express emotion for far longer than we’ve had museums, paints or language. They predate our species as a means of communication, and they remain our most direct conduit, telling how we really feel even when our words deceive.

I make my emotional pigments by collecting pheromones from my pores while watching the TV news. Each sample is classified according to how a news item makes me feel, using standard psychological categories. The pheromones are saturated in linseed oil to produce a palette of colorless paints. My colorless paintings are made with combinations of those oils, thickened to the consistency of putty. Each painting expresses a different combination of mixed emotions for as long as the oil remains wet. They could last several centuries.

Through the mechanism of empathy, spectators can feel what I feel, far more primally than they would through the arcane – and culturally specific – language of Western painting. Moreover, through my mixture of pigments I can create and induce novel emotions never before experienced.

Of course there are other directions you could take this. For instance it could be incorporated into dance, in which each performer would be doused with an emotion and their movement in a room would chemically induce an emotional experience. Or, as you suggest, emotions could be bottled. I think it would be especially interesting to make perfumes with unnatural emotional mixtures that would expand the gamut of human interaction.

How to put a price on it, or, selling space with string theory

MR: Now that you are deep in the market yourself, how do you set prices for your works? Are prices an aspect of your creativity? Part of the work? Are they serious reflections of your work? Or do you think your own prices are philosophical investigations as much as your works are?

Jonathon Keats: When my works are monetized, monetizing them is part of the work. For instance at the height of the 2006 Northern California real estate boom, I paid homeowners for the legal rights to the extra dimensions of space posited by string theory – applying the contractual framework for air rights – and then I sold subdivisions of those extra-dimensional properties through my own real estate agency. Because string theory is unproven, and may not even be provable scientifically, I priced my parcels competitively at 1/100,000 of the Zillow estimate on the base property. My prices were trivial – generally under ten dollars – but the transactions were essential. They were the means by which people participated in the thought experiment. They gave the thought experiment meaning.

In the case of my works of Olfactory Expressionism, the canvases will be sold in the same way that paintings were sold by the Abstract Expressionists and are still sold by artists today. They’ll be exhibited in a gallery, which will issue a price list. All the procedures will be familiar to anyone who’s ever bought art in a gallery before.

Modern and contemporary paintings exist within the context of a market much as Medieval icons existed within the context of religion. This context is an essential part of the experience, a dimension of the thought experiment.

(Of course as we were discussing earlier, pheromones are potent material for other philosophical explorations. If I were working within the realm of perfume, I’d seek to sell the products in a mall.)

But is it ironic?

MR: In 2004 you tried to genetically engineer God in a lab with UC Berkeley geneticists, and sometime afterwards moved in a very different direction, producing ‘extraterrestrial abstract artworks’ based on signals from outer space detected by SETI. In a great deal of your work there is – as far as I can detect – a sincere interest in the universe. Your take is almost that of a Talmudic scholar (and I’m a bit reminded of the film Pi π, without the violent, self-destructive behavior. There is a sense of humor in your work that seems very present in discussions about the universe, God and our origins. What place does irony have in your work?

Jonathon Keats: I sincerely hope that my work is not ironic. Irony is too assertive for my temperament. Like satire, irony has a target, and a point to make. I don’t. That’s why I strive instead to make my work absurd. Absurdity seems to me to be totally open-ended. A situation is absurd when it’s almost familiar yet not quite right. It’s a parallel universe where a few of the rules have been upended. Absurdity is slightly disorienting, and ideally compels us to reorient ourselves with respect to our everyday lives, no longer taking for granted our standard assumptions.

I can’t say whether I succeed, but it’s a strategy I often use. One of the simplest examples is the porn theater for plants I first built back in 2007. I made my pornographic movies by filming honeybees pollinating flowers – titillating if that’s your sexual proclivity – and screened the video onto the foliage of potted rhododendrons for them to experience the play of light photosynthetically. Another more complex example of absurdism was my attempt to genetically engineer God using the scientific method of continuous in vitro evolution.

People often laugh when they encounter these works, which I consider to be a positive response. One of the most attractive qualities of absurdity, in my opinion, is that it’s funny. It’s difficult to be dogmatic when you’re laughing. Humor facilitates genuine conversation.

You mention Talmud, which is one of my great interests. (I even wrote a collection of fables, The Book of the Unknown, based on Talmudic legend.) I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Talmud and absurdism are two major Jewish literary traditions, and that Talmud is sometimes absurd. Both absurdity and Talmudic reasoning resist conclusiveness. And for me there’s no greater enticement than the chance of reaching a higher level of uncertainty.

Collecting stimulates new ideas

MR: Do you collect art at all? What artists interest you? What artists do you like to look at, or like to have in your home? Do you collect anything outside of art? Post cards? Autographs? Books?

Jonathon Keats: I collect most everything in an undisciplined way because the stuff around me often prompts ideas, especially when collections are most disorganized. My home is a sort of Wunderkammer, a cabinet of curiosities. The juxtapositions can be serendipitous, and serendipity is a good proxy for creativity.

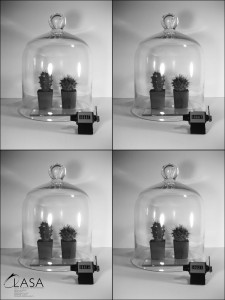

Several years ago, I started collecting meteorites, especially specimens from the Moon and Mars. I had no good reason for doing so, but they unexpectedly led me to start my own space agency. Ordinarily space travel is very expensive, requiring rocketry and toxic propellants. The meteorites I’d collected led me to consider an alternate option: Rather than going to other planets, I could wait for them to come to me. Since I already had some raw material, I started by smashing a piece of asteroid with a hammer and planting two cacti in the rubble. They lived on the asteroid isolated under a bell jar for twenty-one days, exploring the alien terrain by osmosis. (The total cost was about $25, plus $2.99 each for the cacti.)

After that success, I increased the ambition of my program by mineralizing distilled water with pulverized lunar anorthosite or Martian shergottite. I bottled these lunar and Martian mineral waters and retailed them to the public (for as little as $30, considerably less than a seat on Virgin Galactic). As I explained to potential customers, my system is safer than any other means of space exploration, and more convenient even than hailing a taxi. You just sit back and sip. Alien minerals such as pyroxene and maskelynite will gradually build up in your system. Like those pioneering space cacti, you’ll become alien, and you never even have to leave San Francisco or Berlin.

Living the unstructured life

MR: Since your book Forged appeared, have you reconsidered your own work in any way? What’s next for you over the coming few years?

Jonathon Keats: Like my collecting habits, my life is pretty unstructured. One thing leads to another, everything gets mixed up, and I’m usually the last to realize how it happened or to notice the connections. It’s serendipity, again.

A week after my opening in Berlin, I’ll be traveling to New York to install a new work that relates to questions about authenticity – and therefore takes up some of the themes in Forged – though I wasn’t thinking in those terms when I conceived the project.

Simply put, I intend to fix the world economy by using quantum mechanics to generate unlimited money. Naturally I’m going to give the money away to everyone for free.

To understand how this will work, consider the famous thought experiment first proposed by Erwin Schrödinger in 1935, known as Schrödinger’s cat: A cat is put in a box with some poison. The poison will or will not be released based on the outcome of a quantum event. Since quantum theory states that quantum events only have definite outcomes if observed, Schrödinger reasoned that the cat would remain both alive and dead for as long as the box was shut. I’m applying quantum phenomena in an analogous way to generate quantum cash.

Seven billion dollars will be generated for each dollar deposited into a quantum bank with seven billion accounts. The money is deposited by a quantum event: the action of an alpha particle emitted by a uranium glass sphere set inside a grid of seven billion microscopic boxes. The coordinates of each box correspond to one of the seven billion accounts. The box exited by the alpha particle determines which account gets the cash. Were the system being measured, the particle would pass through just one box, putting the dollar in one account, providing the bank with one dollar in total assets. However by encasing the entire bank in metal so that no external measurement can be made, quantum uncertainty will prevail, much as it did for Schrödinger’s cat. The alpha particle will not be constrained to pass through only one box. Since the particle is quantum, it will pass through all of them. All seven billion accounts – one for every human on earth – will be credited. The money will subsist in a quantum-economic superposition.

I’ll install a prototype quantum ATM in the basement of Rockefeller Center on June 11th. Anyone can come to open an account, and to make deposits or withdrawals. And since my technology is all open-source, established banks and governments will be invited to visit, and to emulate my quantum bank on a global scale.

>>Jonathon Keats: On the Wikipedia; Modernism Gallery; the artist’s Forbes.com Column, and the exhibition in Berlin: Team Titanic, Flughafstrasse 50 12053 Berlin. The exhibition opens at 7 PM, 31 May and runs through 7 June.

>>Jonathon Keats, Engineer’s Office Gallery, 20 Rockefeller Plaza (Basement Level), New York, NY, June 11 to June 14. Opening June 11 at 1 pm.