(Lianna’s post explores a project by French artist Camille Henrot that weaves together information about Louisiana’s Houma Indian Nation with ideas about loss of cultural identity and legends.)

In Cities of Ys, her first solo exhibition in the U.S., French artist Camille Henrot explores the ever-changing definition of “culture.” Through video, sculpture, woodcuts and prints, Henrot draws connections between Louisiana’s Houma Indian Nation and the tribe’s rapidly disappearing native wetlands, and other cultures’ flooding myths, including the legend of Ys (pronounced EESS), a mythical drowned city in Henrot’s familial region of Brittany. I talked with the artist and NOMA curator Miranda Lash recently about the project, which weaves together elements of anthropological research and art-making.

If it’s not in writing, it didn’t happen

The idea for Cities of Ys was born a few years ago, when Henrot met a French cultural attaché who was doing a project in Louisiana. The Houma Nation, a community of about 17,000 Louisiana French-speaking relatives of the Choctaw tribe, attracted Henrot’s attention because of their connection to France and French culture—and because the tribe has petitioned for over 20 years for recognition from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and been denied. Oral culture, including the Houma Nation’s rich tradition of storytelling, does not count as criteria for federal recognition. Stories must be written. One of Henrot’s films includes a shot of a paper sign in the Houma administrative office, stating: IF IT’S NOT IN WRITING, IT DIDN’T HAPPEN. “It was putting the question of identity in a very unexpected frame,” explains Henrot. “Does a group need to be identified from inside or outside?”

Henrot’s previous work and her family connection

Culture as a fluid influence is a common aspect of Henrot’s work. Many of her previous pieces have centered around the “other” and “elsewhere,” often examining how cultures borrow from and build on each other. In addition, Henrot feels a strong connection to the Houma Nation’s oral tradition because of her grandmother, a storyteller who originally acquainted her with the tale of Ys. “I’m interested in oral culture because it’s something you cannot really measure and take in your hands,” says Henrot. “Because it’s invisible and fluid, it’s survived a lot. It’s very resistant.”

Origins of the project

After Henrot discussed her ideas for Cities of Ys with Miranda Lash, NOMA’s curator of modern and contemporary art, Henrot and Lash drove to Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, to meet with a member of the Houma Indian tribal council. The artist received the tribe’s permission to undertake the project and visited in December 2012, joining the Houma for a Christmas banquet. Henrot returned to Terrebonne again this past summer, spending several weeks shooting video. “The more I was getting to know the people, the more I was feeling like it was complex and difficult to make any generalization,” she says.

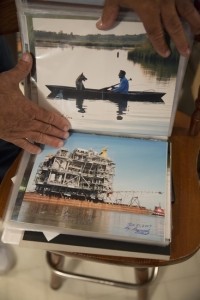

The importance of waterways to the culture

The Houma Nation spans six parishes, or counties; though these communities are distant when traveling by land, they were historically easily accessible by waterway. This is no longer true: coastal erosion, both natural and caused by oil companies laying pipeline, “has left these waterways either nonexistent or impassable and often treacherous,” explains the Houma Nation website. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill that began in April 2010 also invaded the marshes where the tribe hunts and fishes. Now, the Houma face further fragmentation of a community already physically spread thin.

Henrot’s ancestral region of Brittany has also been isolated by erosion. “Even the shape of the land is similar,” Henrot points out.

The installation at NOMA

Water plays a large role in Cities of Ys. The importance of water to the Houma culture is broadcast loud throughout the installation at NOMA. One of the artist’s eight video installations features underwater shots of children swimming in a pool; iridescent oil slicks flicker across the lens. The idea of pools of water is heightened by the flatscreen TV in the gallery at NOMA, which is framed in raw wood, with a kidney bean-shaped cutout through which visitors view the film.

Each video screen in the exhibit has been altered or obscured by this type of frame, which is Henrot’s way of pointing out that awareness of one’s perception is paramount. “Objects make you more aware of the grid through which you perceive reality,” the artist says. “When you talk about a community that people don’t know a lot about, it’s very important to make people aware that just looking at one point of view is not the whole story.”

In the same vein, Henrot layers multiple images in her videos, combining visual elements of Louisiana’s oil and fishing industries—pipelines, pirogues (small, flat-bottomed boats used in fishing)—alongside interviews with Houma Nation members and scenes of lapping water.

A laptop open to a long, scrolling Wikipedia list of French-to-English phrases highlights the often slippery transfusion of cultures. This screen, and the others throughout Cities of Ys, doubles as a reference to the globalization that Henrot sees pervading different cultures. “Sometimes something that seems very specific or local is happening in different parts of the globe,” she says.

“So often, people are interested in the Houma, and they take what’s interesting to them and they go off and the Houma don’t ever get to hear what happens,” says Lash. “Because Camille’s project is about ‘What are the parameters of culture?’ and how culture is defined, we asked, ‘How do the Houma define Houma?’”

In response, the tribe requested to display its traditional basketry, which is on view adjacent to Cities of Ys in an exhibit entitled Woven Histories: Houma Basketry.

Underscoring the idea of cultural connection, Henrot’s project literally weaves itself into the basketry exhibit; her futuristic 3D fiberglass interpretation of a South Louisiana pirogue juts through the wall between the two shows. This sculpture is called “Descendants of Pirogues,” and features smaller boats stacked on the prow of the largest, bringing the idea of family generations (and Russian nesting dolls) to mind.

Other works in Cities of Ys include simple prints of organic shapes made from wood left over from the manufacture of guitars, which Henrot sees as an “iconic American symbol.” Her choice of the guitar to represent America is interesting considering that one aspect of the project is an examination of who chooses which elements of a culture as most important or representative, and which can be lost or left behind.

Though Henrot mainly focuses on Louisiana and the Houma Indian Nation for Cities of Ys, she believes that the project has wider implications. “The situation they are in echoes a larger question: what is the destiny of cultural patterns in a global era?” says Henrot. The exhibit does not attempt to answer its own questions, instead supplying information and allowing the visitor to draw her own conclusions.

Camille Henrot’s Cities of Ys is on view until February 23rd at the New Orleans Museum of Art. All images courtesy the of the artist and gallery kamel mennour.

See more of Lianna Patch’s writing at her website, the english maven.