[Andrea accesses a behind-the-scenes look at the Barnes Foundation’s current Matisse research and conservation projects; she suspects the finished result will offer considerable insight into the artist’s technique. — the Artblog editors]

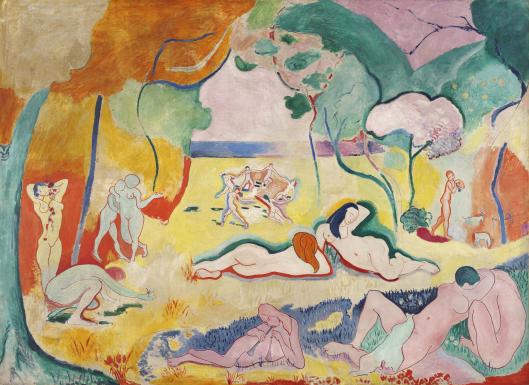

I was fortunate to be able to join a group of the Barnes Foundation’s upper-level supporters last week for a preview of the Foundation’s research on its substantial collection of works by Matisse, which includes two paintings essential to understanding the artist’s development: “The Joy of Life” (1905-06), crucial to the artist’s early development, and “The Dance” (1930-33), a mural commissioned by Dr. Barnes for rooms housing his collection. Matisse used cut paper in designing “The Dance,” anticipating his use of cut-out, painted paper in his last works, in the 1940s.

Research on the Matisse project began in 2004. It will culminate in a catalog of the Barnes’ Matisses, to come out in 2015, which will include 11 scholarly essays, as well as information on the conservation history of the works and on the artist’s painting technique. This publication follows the 2012 volume, Renoir in the Barnes Foundation.

Conserving color

Most of the evening’s discussion was conducted by Barbara Buckley, chief conservator at the Barnes. She spoke of evidence of color changes in “The Joy of Life,” using slides, since the painting was too large to easily move into the laboratory. The changes were in areas painted with cadmium yellow, and included paint that lightened and was flaking in one area, and darkening paint in another. Cadmium yellow has traditionally been thought to be stable, but there were problems with its manufacture at the time Matisse used it.

Prior to the development of a range of new, synthetic pigments in the 19th century, most yellows (as opposed to golds) available to artists were organic, and had to be adhered to an inert base to function as pigments. Organic colors are well-known to fade in the presence of light, so the synthesis of pigments in which the color derived from inorganic, crystalline structure was an advance. However, some synthetic pigments also proved unstable. Critic Felix Feneon famously detected changes to Seurat’s “Grande Jatte” in areas using zinc yellows and greens made from the pigment, within five years of that painting’s first exhibition. Properly trained conservators would never attempt to recreate the original colors, but computer technology now allows for virtual treatments that at least give an idea of the artist’s original palette.

Barbara Buckley took the small group of us into the beautiful, new conservation laboratory. I had visited her in Merion, where the lab was in the basement, and it is clear that conservation is now being given a much higher priority at the Barnes. The light-filled space was designed by Samuel Anderson Architects, which has become the go-to firm for conservators, having designed conservation laboratories for MoMA, the Morgan Library, the National Gallery of Art, the Strauss Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard University Art Museums, the Whitney, and others.

Getting down to details

While the Barnes Foundation paintings, contrary to much myth, had received conservation treatment from the time Barnes acquired them, and sometimes prior to that, the conservation records only date to the 1980s. We were able to look at three Matisses that had been removed from the walls and taken out of their frames. “Small Jar” is a very small painting–5 3/8″ x 7 3/16″–on paper that had been affixed to board. It retained evidence of the paper having been folded, in the form of a horizontal line, slightly below the middle of the support.

Viewing a portrait of the artist’s wife, “Red Madras Headdress,” on an easel allowed us to see the back, which revealed both a maker’s mark, from the firm that stretched and primed the canvas, as well as Matisse’s fingerprint in the aquamarine paint he used for the portrait. Despite his renown, Matisse’s painting technique has had remarkably little scholarly attention, so the information the Barnes publishes as part of the forthcoming catalog should be a significant contribution. I’m looking forward to it.

Jennifer Zarro wrote here about her recent visit to the Barnes’ conservation lab to learn more about Cezanne’s technique.