[Irena enters the dark, sometimes grotesque world of David Lynch’s visual artworks, which explore themes of danger, family, and sickness, and which are inextricably tied to North Philly. — the Artblog editors]

The area of North Central Philadelphia around the corner of 13th and Wood streets is desolate and grim, with a characteristic vagueness that accompanies post-industrial abandonment. This particular no-man’s land is known fondly to locals as the “Eraserhood”–and with good reason.

Early work flavored by Philadelphia

The Eraserhood’s namesake is David Lynch’s iconic 1977 body-horror film, “Eraserhead”. A reluctant father is faced with a bitter girlfriend and a mutant spawn of a new baby while battling the conditions of his surreal surroundings. The setting is, of course, the Eraserhood, or at least a Lynchian version of it.

Lynch, a promising albeit peculiar young art student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA), officially enrolled in 1966 after a brief stint in Boston. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, the young artist resided at 13th and Wood, across from the city morgue, and subsequently at 24th and Poplar. In the gray isolation of Philadelphia’s pre-urban rejuvenation, Mr. Lynch sponged up his most prominent and captivating imagery. As a budding young painter and eventually a celebrated filmmaker, everything Lynch did, and is doing, is doused with the shocking, atypical, and effortlessly bittersweet flavor of the City of Brotherly Love.

On these terms, it is highly appropriate that Mr. Lynch’s first major U.S. art exhibit is now taking place in Philadelphia. David Lynch: The Unified Field opened to the public on Sept. 13 at PAFA, the very school whose halls Lynch once haunted. The exhibit allows Lynch’s unique relationship with Philadelphia to project itself through a number of rarely seen paintings, drawings, prints, and mixed media pieces, spanning almost 50 years of the acclaimed filmmaker’s career.

The special place Philadelphia occupies in Lynch’s heart becomes evident when he recalls how the city impacted his artwork, and why. “The filth, the corruption…despair…violence…was all so beautiful to me,” Lynch affectionately stated during a press conference at PAFA earlier in September. “Philadelphia is my biggest influence,” he asserted, contemplating the earlier days, his iconic swoosh of hair still intact after all these years.

How Lynch sees “home”

The Unified Field serves as an important tribute to the versatile and often-obscene quality of Lynch’s mind. But whatever you do, don’t call it a retrospective. Robert Cozzolino, the show’s curator and chief curator at PAFA, insisted to me when I spoke with him prior to the show’s official opening that “Lynch was not interested in a retrospective.” Instead, he wanted to focus on where he came from, and the types of themes that manifested in his development as an artist.

A recurring theme in many of the pieces that are a part of Unified Field is home. Home–a place that promises safety and security, but as Cozzolino puts it, it is “a place where things can go horribly wrong.” While Lynch resided on 24th and Polar, he and his young family had their house broken into several times. In 1970, Lynch filmed “The Grandmother” at the very same location; in this film, a young boy is terrorized by his parents, and in turn grows himself a kind grandmother to combat the abuse. This early film is on view in the gallery.

A number of disturbingly blunt and expressive pieces in the show explore the devastating possibilities of what exactly can go wrong when a home’s fragile safety net is punctured. In addition to “The Grandmother,” the grim matter of works like “Pete Goes to his Girlfriend’s House” deals with tragic situations that are about to happen; their outcomes are usually unclear.

Bodily trauma

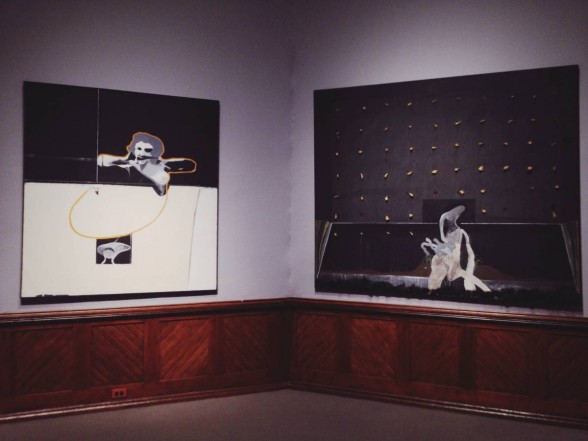

A number of Lynch’s works literally extend from their canvases with the use of various mixed-media materials. His paintings, if you can even call some of them paintings in the traditional sense, are often given a sculptural effect by the addition of varying objects and organic matter. In the delightfully grotesque “A Figure Witnessing the Orchestration of Time,” a number of resin-coated fly carcasses are mixed within the paint craters.

Lynch also takes on trauma occurring to the body, and traumatic states of being, both physical and emotional. In the very first room of the exhibit, one of Lynch’s earliest works as a PAFA student is “Man Throwing Up,” a three-dimensional, mixed-media work of paint and resin that greets onlookers with a spewing, protruding face.

One of Lynch’s first film works

One of the most captivating pieces in the entire show is “Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times),” an installation-esque short film projected on a wall in a small, enclosed space. It invites viewers to step inside and experience the very first manifestation of Lynch as filmmaker.

Philadelphia is a very different place since the last time David Lynch inhabited its streets. Lynch recalls, with some regret, that Philadelphia is “cleaner…not as cut off from the world as it used to be.” The Unified Field not only allows us to glimpse the filmmaker’s twisted world, but shapes his identity as a painter and artist and of course, a Philadelphian.

We Philadelphians still need Lynch to force us into finding the beauty in terror and the important narratives within modern ruins, both industrial and psychological.

David Lynch: the Unified Field is on view through Jan. 11, 2014 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Historic Landmark Building, 118 North Broad Street, Philadelphia. More information at www.pafa.org.