[Donald gets a chance to hear some never-before-heard tracks by Bruce Haack, one of the forebears of modern electronic music. — the Artblog editors]

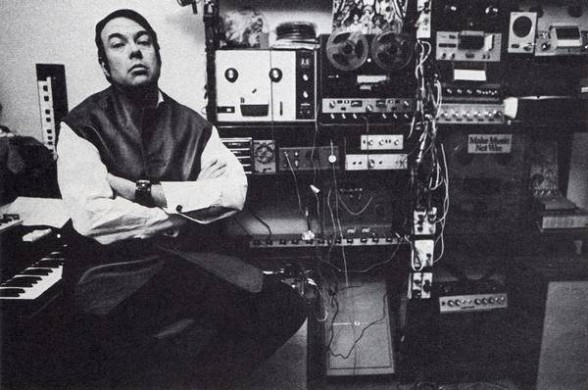

Electronic music has been infused into so many genres today (particularly pop music) that it feels all too familiar. However, a man by the name of Bruce Haack practically invented the art form, creating his singular brand of futuristic music as early as the 1950s. Haack was an innovative music-maker so ahead of his time that his music didn’t achieve its true reach until after his passing in 1988.

The running line mentioned throughout a short biography created specifically for a recent event celebrating Haack is that success always seemed to elude him. He was too ahead of his time, too smart, and too peculiar. You can immediately hear how his forward thinking clearly influenced many electronic artists in the decades to come, especially Daft Punk.

An intimate “listening party”

When I heard that <fidget>’s Experimental Music Festival was hosting a Bruce Haack listening and remixing party with co-director Peter Price, I leapt at this unique opportunity. After all, how many times can you say, “I went to a remixing party”? I experienced this as more of a deep listening session than a party, per se.

The party took place on Friday, Nov. 7 at the cozy <fidget> space in the Fishtown section of Philadelphia. A medium-sized group of people was seated, quietly eager to hear some unknown Bruce Haack gems. <fidget> is a platform for the collaborative work of Megan Bridge (choreography) and Peter Price (time-based media). Bridge and Price create awkward dystopias, referential and even appropriationist, grounded in the discourses of contemporary art, culture, and theory.

At the party, Price took the audience through Haack’s musical life, from 1955 onward. He read from his notes through the duration of the session; it would have been 100 times more engaging if all of the interesting Haack information were part of a PowerPoint presentation instead.

However, it was wonderful to learn little tidbits about Haack, like how he attended Juilliard as a music composition major for only eight months, didn’t have a typical work ethic, and had a strange obsession with Christmas. The audience was lucky to be joined by one of Haack’s closest friends, Ted Pandel. Pandel, an accomplished pianist and retired professor, was a classmate of Haack’s at Juilliard and collaborated with him a great deal. Pandel was called upon several times in the evening to talk about specific periods in Haack’s musical output.

In a once-in-a-lifetime situation, Price got the go-ahead to digitize, play, and remix unheard basement archival material by Haack, live for the <fidget> crowd. One of these pieces was the 12-minute “Les etepes,” originally recorded in 1955. This work is a hodgepodge of sounds: a creepy operatic singing voice, a sensitively phrased violin solo, haunting echoes, duck shrieks, random drum line cycles, vaudevillian upbeatness, and Haack’s signature space-age sound. To me, “Les etepes” is almost like an electronic version of Igor Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” as it is an exhilarating and challenging piece for any seasoned music listener to sit through–yet these sounds were unprecedented, especially in a time period when rock and roll was dominating the airwaves.

Unusual recording methods and collaborations

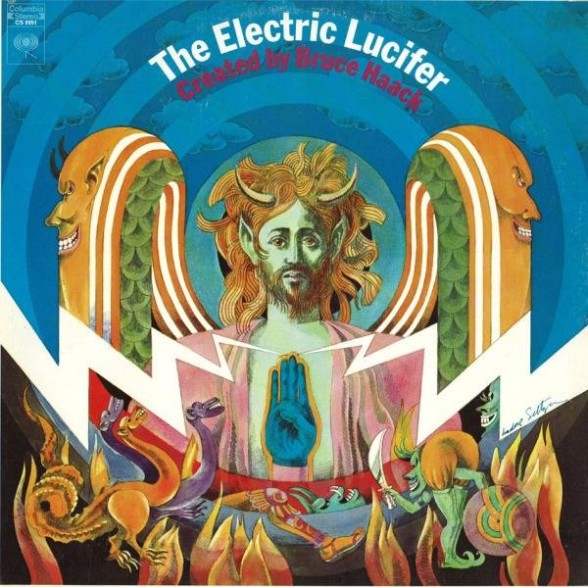

Haack’s musical palette was wide–ranging, from composing incidental music for Broadway plays, and postmodern classical works, to his acid rock/anti-war album The Electric Lucifer and collaboration with hip-hop pioneer Russell Simmons on “Party Machine”. When Price spoke of The Electric Lucifer–Haack’s only album on a major label–he revealed how it was a revolutionary album in that the entire work was recorded in Haack’s home studio. In 2014, recording in a home studio is all too common, but in 1970, this practice was rarely ever done, especially with a major-label release.

Haack’s music also had a wonderful sense of humor. When Price played Haack’s 1966 composition “Computer plainchant,” the effects used sounded an awful lot like high- and low-pitched farts.

If the origin of electronic music fascinates you, as it does me, Haack’s The Electric Lucifer album is a great place to start as it is considered Haack’s crowning achievement. The best art often tends to be the most polarizing, and its divisiveness can cause it to be shoved aside in the heat of what’s more accessible. It’s satisfying to see that Bruce Haack and his music can finally be appreciated for daring to be different, and even strange, for the benefit and result of some of the coolest music ever made.

For more information on <fidget>, click here.