[Noreen explores the origins and evolution of Fraktur, a decorative style of documentation with deep roots in Germany, which is coupled with contemporary art in a current exhibition. This post was assigned and shepherded through the editing process by our guest editors this month, the Nicola Midnight St. Claire. Thanks, Nicola! — the Artblog editors]

In an age when computer graphics are almost entirely responsible for design, handmade birthday cards, wedding invitations, and journals are rare and special. This month, in partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Free Library of Philadelphia presents a collection of such rarities on display in its exhibition series Framing Fraktur. These 18th- and 19th-century hand-painted and -printed documents, many created in rural areas surrounding Philadelphia, commemorate the milestones in the lives of the German-speaking immigrants of these areas. Coupled with the work of contemporary artists, Framing Fraktur explores cultural identity and individual expression through both the past and present, as well as the local and international.

Humble outsider art

Wove paper; watercolor; ink; graphite

[Daniel Otto (c. 1770-1822)] Decorator and Scrivener

Haines Township, Centre Country, Pennsylvania

ca. 1820

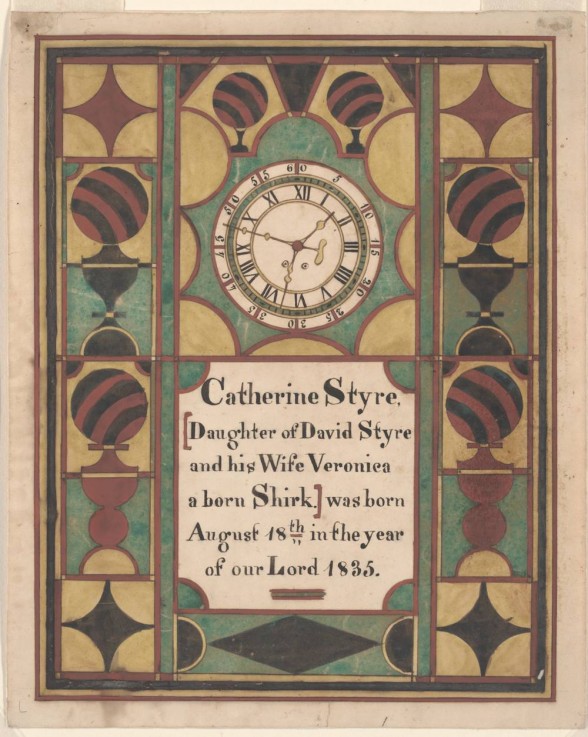

[Samuel Bentz (1792-1850)] Decorator and Scrivener

[Lancaster, Pennsylvania]

ca. 1835.

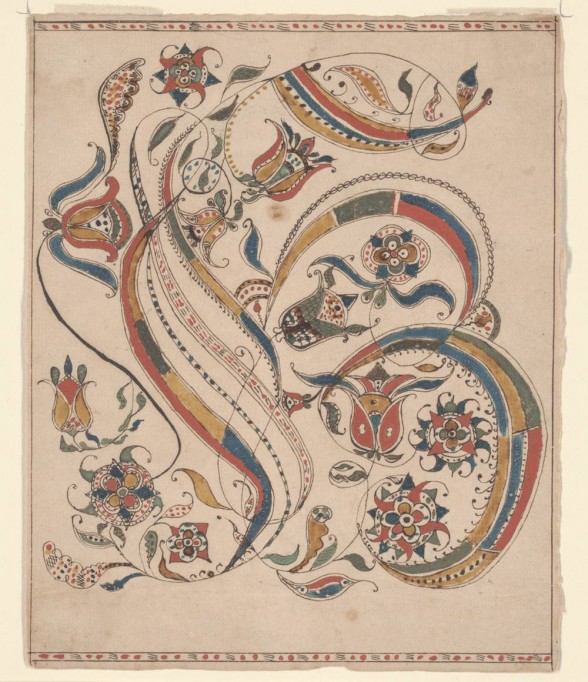

Personal, private works

[Susanna Hübner (1750-1818)] Decorator and Scrivener, [Worcester Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania], ca. 1810.

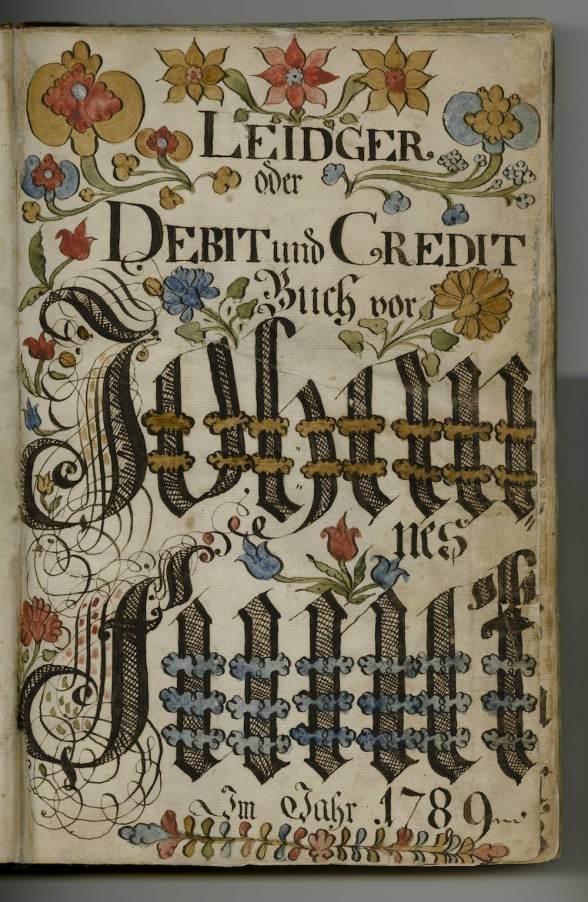

Authors : John Funk and Samuel Funk, Attributed to Johannes Ernst Spangenberg (c. 1755-1814), John Funk and Samuel Funk Scriveners, Springfield Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania,

ca. 1789 – 1850.

Contemporary connections

In stark contrast, the contemporary artwork of Framing Fraktur, grouped in an exhibition called Word & Image, features artists from varied origins using a wide variety of media. Unlike mostly-untrained 17th-century Fraktur artists, who created work for private use, the artists of Word & Image have received formal training, consciously making art for an audience. Their choices in media range from woodblock print, embroidery, and watercolor to more sculptural media–such as reclaimed wood and tapestry. Despite these divergences, the contemporary work clearly roots itself in the age-old traditions of Fraktur. Through meticulous attention to text, type, and symbology, the artists bridge the cultural and temporal gap between the two bodies of work.

Though the multifaceted exhibition series may seem extensive, the view of both contemporary and historical work is essential to the understanding of Pennsylvania’s history, folk art, and our contemporary notions of it. Where as before, the viewer may have conceived Fraktur as only typical folk art, Framing Fraktur’s contemporary aspect refreshes the notion of art made for personal, intimate uses. Through this new recontextualization, Framing Fraktur gives Pennsylvania’s rich art history a new light, celebrating Pennsylvania German Fraktur as an expression of cultural identity in daily life.

The exhibitions of Framing Fraktur are on display at the Free Library of Philadelphia until June 14, 2015, and at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Perelman Building until April 26, 2015. Visiting hours vary.