Architecture is in many ways one of humankind’s most potent assertions of might. It can represent our dominance over the natural world, our ability to convene and coexist to survive, as well as symbolize our greatest achievements and dreams in material form. It can also stand as a reminder of the misguided authorities of the past. In The Past is a Foreign Country, Francois-Xavier Gbré uses architectural photographs of West Africa and elsewhere to bring us face-to-face with failed construction projects that came from the mouths of politicians and CEOs who promised prosperity but failed to deliver.

Bearing witness to decay

French-Ivorian Gbré examines these empty promises through architectural photographs of a vacant construction site in Senegal, a dried-up Olympic swimming pool in Mali, and a former national printing house in Benîn, among other locations in the region and in his native France.

The cities that Gbré visits and photographs are filled with partially-funded and poorly built constructions that have degraded to less than a shadow of their original purpose–to unite and give hope to the people who live there. These buildings have what Brendan Wattenberg calls, in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, “a brief second life as purely aesthetic objects.”

Natural vs. constructed

Gbré grew up in Lille, France, and was influenced by the industrial decline of his own hometown in relation to that of the nations where he would later work. The exhibition, held at the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, is his first in North America and was commissioned as a site-specific installation. Large-scale loose prints hang from the walls, in conversation with oversized wallpaper prints and a collection of postcard-sized images satisfyingly arranged on the far wall of the gallery. The scale is meant to be immersive, and it does pique the imagination of the viewer. You start to wonder about the smell of those stagnant swimming pools and rivers of red mud, hearing the sound your feet would make on the floors of abandoned government buildings strewn with decades-old paperwork.

One of the most noticeable visual trends in the work is the conflict between natural landscapes and constructed real estate. So many of these buildings are out of place, both in style and function. It seems their designs were chosen less for what daily life in Africa requires and more for the ideologies that they came to represent in their places of origin. Suburban-style homes and housing developments with tiny windows and concrete walls inappropriate for the climate of West Africa emerged after the clearing of large slums and low-income areas, hoping to deliver the “Ivorian dream”. The red mud in this photograph is, according to Gbré, is “the only element that says you are in West Africa.”

Material degradation from a dying industrial culture can be found in every part of the world–from Detroit to central Asia and beyond. The photographers who flock to document this phenomenon have made work that has earned the label of “ruin porn,” arguing that this work has in fact aestheticized the suffering of real people and contributed to the exploitation of struggling communities. Aesthetically, some of Gbré’s less enticing work harkens to this style. Conceptually, his motives and musings are sincere and well-wrought, but the end product does not always reflect this care, such as the pictures made in an abandoned Unilever factory in France.

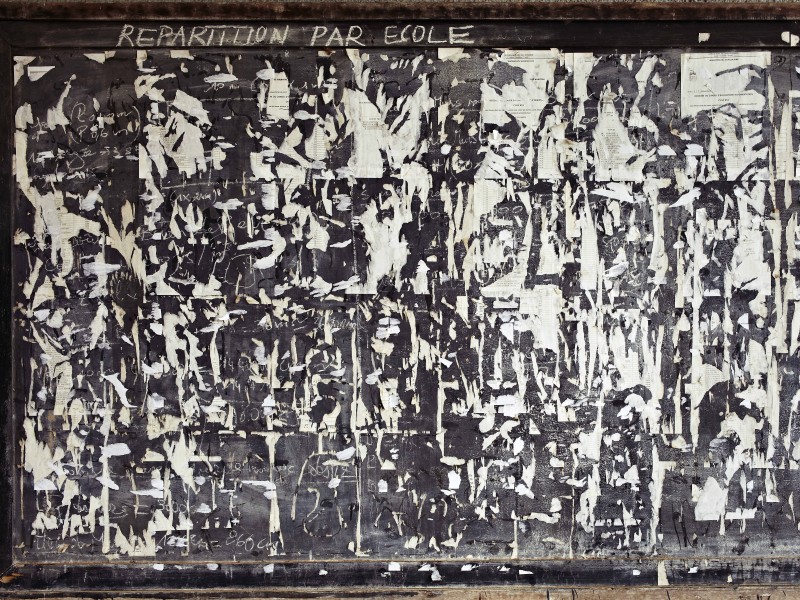

The most affecting photographs depict scenes that seem more happened-upon than meticulously planned. “Neon #1,” for example, addresses in deadpan fashion the almost universal hollow feeling of fluorescent light, which inevitably reminds me of William Eggleston’s famous image “Red Ceiling or Greenwood, Mississippi, 1973”. “Repartition par école, Bingerville, 2014” is also arresting in its simplicity, with peeled paint and faint writing forming a textural landscape of decay.

The image that fascinates me most does so because of its normalcy and the symbolism it contains. “Voiture #1, Attoban, Cocody, Abidjan, 2014” depicts a car wrapped up in an elastic cover–parked in an otherwise empty lot and against a backdrop of sharply manicured hedges. The image really could have been taken anywhere. The car loses all defining features save for a rear wheel peeking out, and evokes the imagery of a house under construction wrapped in plastic.

It’s a quietly powerful scene, one that also draws to mind Robert Frank’s “Covered Car” picture. Beneath that protective layer lies an unattainable mystery just out of reach, the freedom that a car allows and the ideals of leisure in modern life. It’s a fitting metaphor for West Africa’s growing pains and the journey of reparation that lies ahead.

Interestingly, I had a similar experience viewing this show as the last photography exhibition I saw at Cantor Fitzgerald, Zoe Strauss’ Sea Change. Both were socially conscious efforts to examine the aftermath of tragic circumstances on the landscapes in which they occurred, and both were just slightly less visually gripping than their well-intentioned conceptual backbones. Gbré’s The Past is a Foreign Country is still very much worthy of a visit, however. You’ll find that the pictures make one thing clear–the promise that West Africa contains lies not in corruption-plagued architecture brought by corporations and politicians, but elsewhere.