Wu Hung, Contemporary Chinese Art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014). ISBN 9780500239209

Click here to see the book on amazon.com

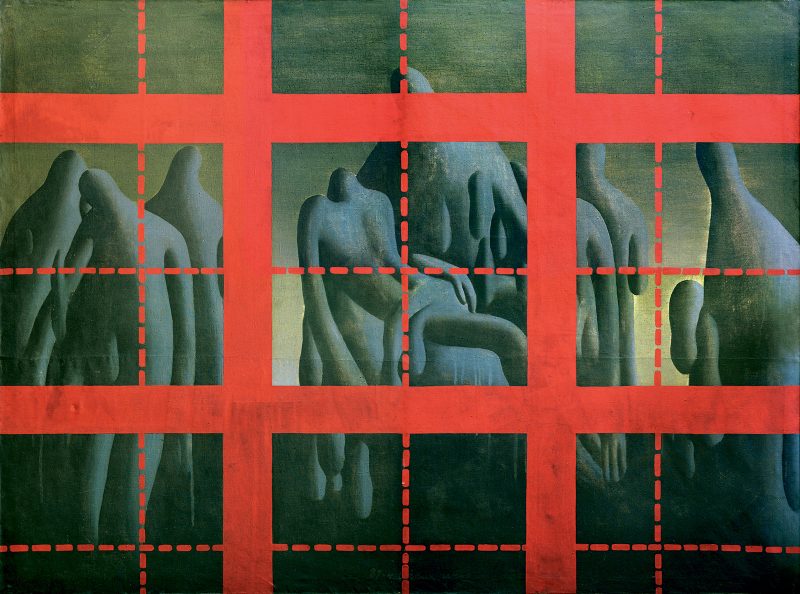

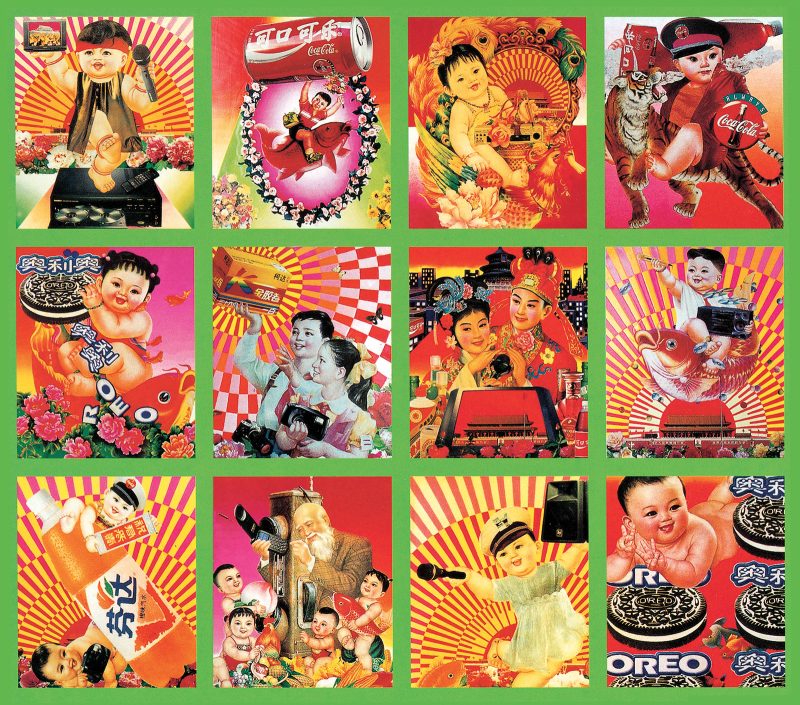

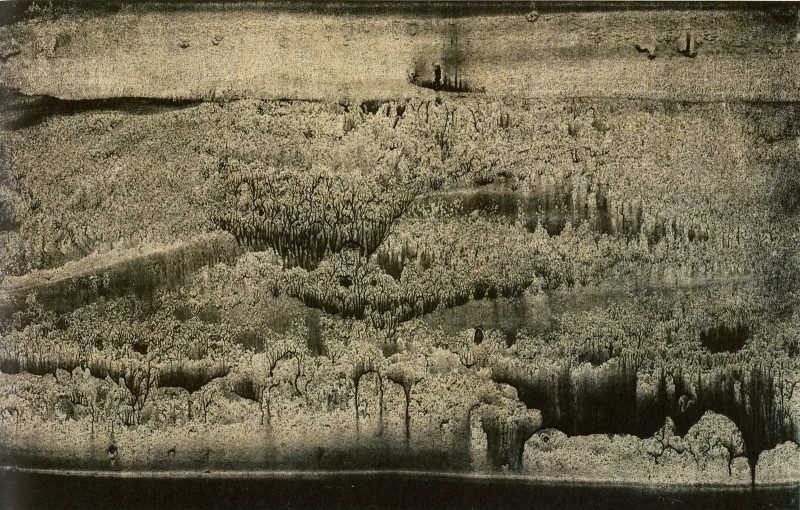

Wu Hung charts the astonishing history of Chinese art since the 1970s, when China emerged from the near total isolation of the Cultural Revolution to become a major participant in international exhibitions and markets. The author is Director of the Center for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago and a historian, critic, and curator of Chinese art. His approach encompasses a broad concept of art culture which includes art schools, community art centers, public art museums, individual artists, artist collectives and groups, art publishing and criticism, and the recent phenomena of commercial galleries, art fairs, private museums and Western audiences. It is a more nuanced and complete picture of a recent art culture than any other I know.

The superb text is extremely clearly written and jargon-free, yet manages to convey the complex relationship between individuals and institutions involved in the transition. The author lived in China during the early part of the period covered and has maintained regular contact since, and the book reflects his insider’s knowledge.

Wu traces the significance of how information circulated, from artists during the Cultural Revolution who poured over any books on Western art that they could obtain, to the situation since the 1980s when China’s art press included three journals, each with a different approach, and artists had access to Western writings in translation, including arts writing by Herbert Read and Ernst Gombrich, philosophy by Kant, Nietzsche, and Wittgenstein, and significant thinkers including Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Charles Darwin.

Art production included official, state-sponsored art, art which came out of the academies that were re-organized after the 1970s, and experimental art produced by collectives and unaffiliated artists. Officially trained artists studied either Chinese art–ink painting–or Western art, and Wu discusses the tension between contemporary Chinese art grounded in Chinese art traditions, versus that which takes a thoroughly international approach. He also discusses the tension among independent, avant-garde artists recently, once state museums began to exhibit previously banned work; some saw the move as progress while others considered exhibiting in state museums as collaboration with the state. Wu addresses the impact of larger cultural changes on the art culture, including China’s commercialization, population mobility, and increasing access to outside cultural and artistic influences. He also covers the interactions between artists’ activities and their interpretation by critics, how critics’ ideological positions shaped and defined art movements, and the significance of critics as organizers of artistic events and theorizers of art movements–hence, shapers of China’s art history.

The book is extensively illustrated–its 425 color images could stand alone as a visual survey of Chinese art of the period; but that would ignore the immense value of Wu’s text. The book is beautifully produced, and its un-credited designer did a wonderful job.

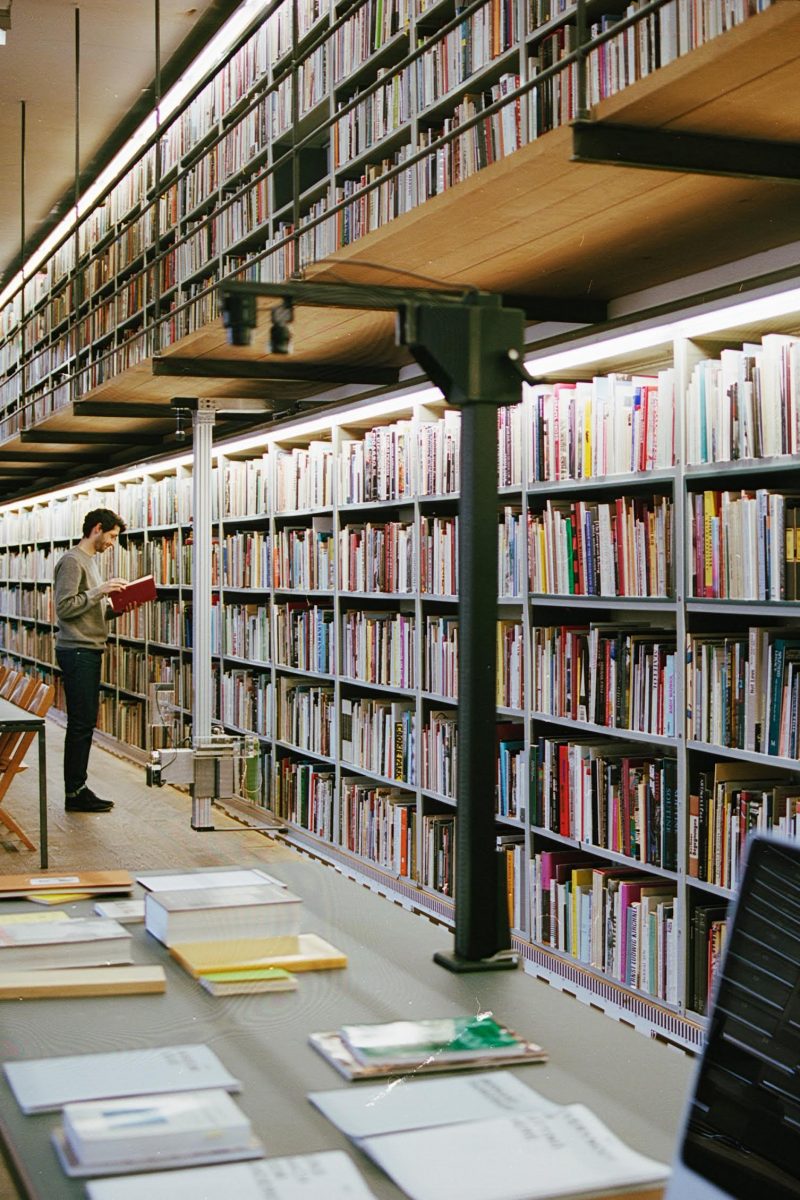

The Dynamic Library: Organizing Knowledge at the Sitterwerk––Precedents and Possibilities, edited by Ariane Roth and Marina Schütz, translated by Alta J. Price (Chicago: Soberscove Press, 2015). ISBN 978-1-940190-09-9

Click here to see the book on amazon.com.

All systems of classification are man-made and individual. This point was made most memorably by José Luis Borges, when describing a Chinese encyclopedia that divides all animals into 14 categories: “Those that belong to the emperor, Embalmed ones, Those that are trained, Suckling pigs, Mermaids (or Sirens), Fabulous ones, Stray dogs, Those that are included in this classification,…”

Ordering systems have been of interest to many artists over the past several decades–likely spurred by Foucault’s citation of Borges in the preface to The Order of Things (1970). The subject will always be of central importance to librarians and archivists.

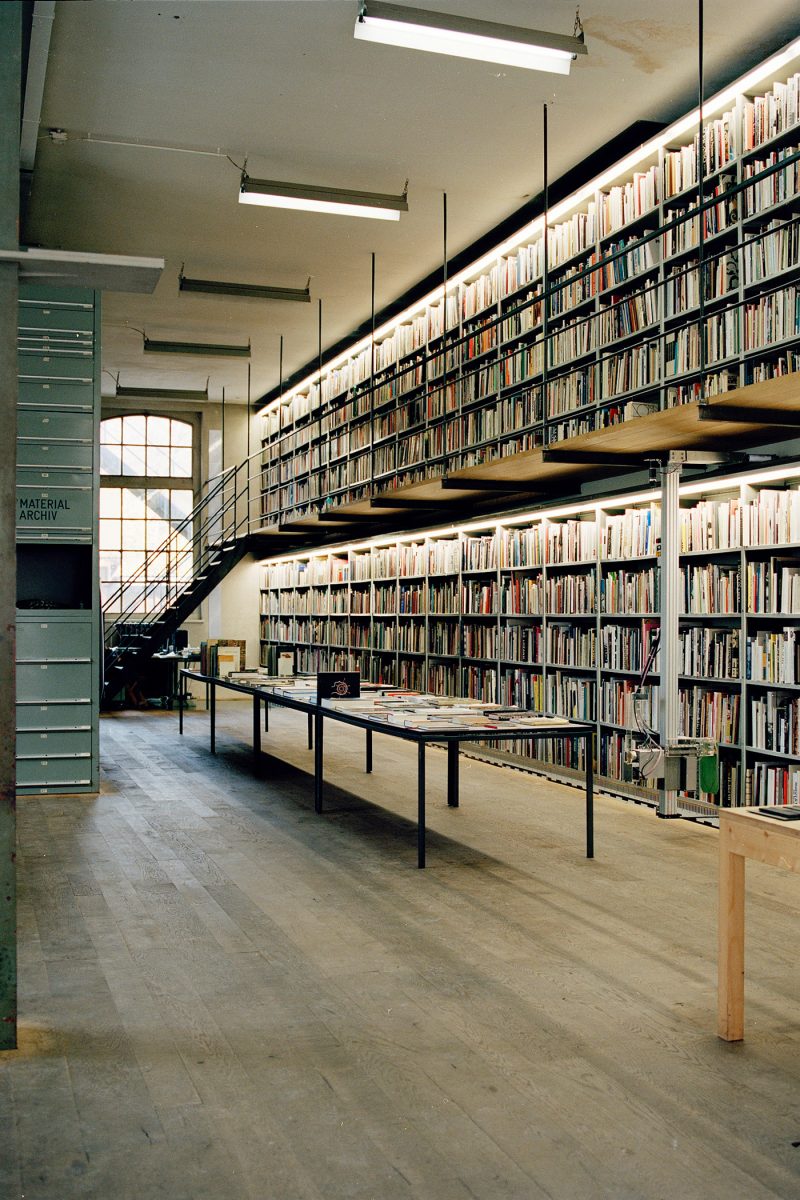

This fascinating, small book is the product of a symposium held in connection with the opening of Sitterwerk’s Kunstbibliothek in St. Galen, Switzerland in 2011. Sitterwerk is a foundry, with a Foundation that supports a material archive, art library, exhibition space, and studio house. The majority of the contents of the art library of 25,000 volumes came from a single donation from the book collector Daniel Rohner. As with most private collections, his was arranged according to his own needs and interests. The foundation decided to maintain the library’s private character, which required a dynamic organizational system.

The idea behind the organization is to allow researchers to assemble books grouped around their own interests, creating unexpected juxtapositions for subsequent library users. Books are tagged internally, to maintain their integrity as objects–and a Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) system surveys the holdings daily, noting each book’s location. Readers can also add their own comments to the system–virtual marginalia.

The symposium addressed classification systems, art, and new orders of knowledge, with 17 participants contributing to the book. They include art historians, an agricultural scientist (RIFD technology was developed in aid of animal husbandry), artists, designers, librarians, and media scholars. They present a variety of historical and theoretical approaches in clear language that are likely to interest scholars in the humanities, artists interested in classification, and anyone who owns enough books to be concerned with how to sort them.