The double bill at the Film Forum will take you 90 minutes. It’s a must-see 90-minutes. The documentaries on Elizabeth Murray, (“Everybody Knows…Elizabeth Murray” by Kristi Zea) and Carmen Herrera (“The 100 Year Show” by Alison Klayman) immerse you in the biographies and studio practices of two artists who had spark and ideas, worked hard, never gave up, and are examples to us all.

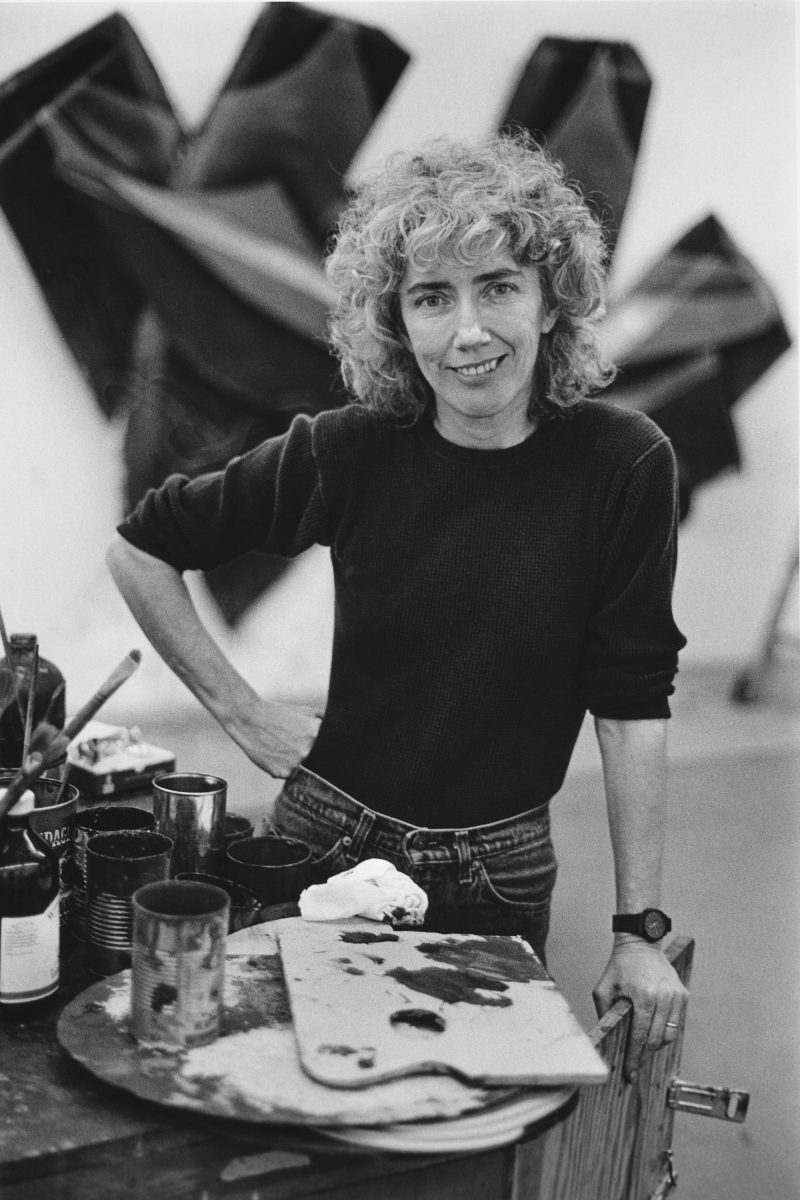

Elizabeth Murray’s works delight curators, critics and the public

Kristi Zea’s “Everybody Knows…Elizabeth Murray” (2016, 60 minutes) is a beautiful film in a classic documentary style. The major New York tastemakers — artists, critics, curators — are all there, orating about the wonderfulness of Murray. Chuck Close talks about what a miracle it was for her to work on a sculptural canvas. Robert Storr says she upset the conventional wisdom, and people don’t get thanked for that. Adam Weinberg says you don’t think of the high arts as zany or goofy, but her work is. Jerry Saltz calls her heroic and says she had an original idea of beauty. The Guerrilla Girls make a notable appearance and call her “a feminist without having to say it.”

The film is nicely paced, with studio shots of Murray painting — on a ladder, sitting on a chair, standing — interspersed with the commentary, with family snapshots and films, and with the artist talking about her life and work. Murray (1940-2007) kept a journal and some of the best parts of the movie are Meryl Streep reading from Murray’s journals while the film shows Murray painting, and the screen overlays the journal pages. It’s nicely done.

Murray’s life is a revelation. Told with family photos and her own stories, the most poignant biographical detail is that as a young child her family was homeless and coped by riding the Chicago El all night or sleeping in a hotel then sneaking out early to avoid paying the bill. The family must have stabilized later, and when Murray was in high school in Bloomington, Il, she excelled in art. And a supportive art teacher sent her to college at the Art Institute in Chicago. Married twice, with three children, Murray is described by her gallerist, Douglas, at Pace Gallery, as sweet-natured but tough as nails. “I am driven,” she says, later on in the movie, and it echoes. She’s also described as a woman who didn’t know she couldn’t have it all — marriage, children, career. There’s a sweetness in the scenes of Murray and her children. Mom seems like a nice woman — the kids are darling. But Murray also spent a lot of time in the studio in the barn and the kids seem to have run free on the farm while mom was painting. Everyone grew up great. Lesson learned – no harm done when mom needs to paint and the kids get a little free time.

About her works, Murray says she was trying to not have an image and have an image. “People liked it and I pushed more,” she said. In answer to why she split apart her paintings into jigsaw puzzle pieces she says “I like to paint edges.” When her split canvas paintings came out people initially wrote about them in reference to Frank Stella’s sculptural paintings. She didn’t like that comparison — and apparently Stella didn’t either. Her subjects were always from daily life, not the mystical — shoes, broken coffee cups, telephones and tables, cats and people. Stella’s works allude to great literature and echew the personal. There’s really no comparison.

It came as a surprise, but it makes perfect sense to hear that while at the Art Institute in Chicago she met and wanted to be part of the Hairy Who, the group of cartoony non-narrative imagists that included Ed Paschke, Jim Nutt, Ray Yoshida, Karl Wirsum. Much of her work is kindred in spirit to theirs — fierce, cartoony, non-narrative, unique — really like nobody else’s.

Murray died of lung cancer in 2007 and was sick during her 2005 retrospective at MoMA. She’s one of only five women who’ve had retrospectives at MoMA. The film ends with two outtakes from a memorial held for Murray after she died. Meredith Monk plays a jaw harp – some kind of plaintive, twangy, and quasi-comical tune. Trisha Brown dances a worm-like wiggle on the floor that goes on and on. It was a funny way to end, but seems in keeping with Murray’s sensibility of friendliness, experimentation, confidence and celebrating the quotidien.

101-year old Carmen Herrera gets her due

Alison Klayman’s “The 100 Years Show” (2015, 30 minutes) is a quiet movie. The artist, who is 101 in 2016 (she was born in 1915) is physically frail and in a wheelchair. But her mind is agile and her wit is sharp. The best moments in the film are Carmen talking.

“There’s a saying. If you wait for the bus the bus will come. I waited almost a century and the bus came.”

About painters block – “I don’t understand it.”

She wishes her husband, Jesse Lowenstein, would have seen how popular she is.

They tried to have children but they never came. “If I could tell you (why) I’d tell you. But I can’t. I make art.”

“I like a battle. I don’t like to get hurt but I like a battle.”

About being with the “big boys” of the art world — “It’s about time. Better late than never. Earlier would have been nice.”

There is Latin-jazzy music in the film that plays over scenes of Herrera working at a table, with her assistant, Manuel, selecting colors, masking off the straight edges, and making new works. Dana Miller, Curator at the Whitney Museum, asks her questions. Herrera’s biography unfolds with family photos and the artist telling stories. She was born in Cuba. Her father founded the El Mundo newspaper. Mom was a feminist and didn’t believe in her art. She married Jesse Lowenstein in 1938, when she was 23. He was a Bronx-born photographer who met her in Cuba. They moved to Paris and lived there from 1948-1953 and came back to the US when Jesse couldn’t get a job. She painted hard-edged geometric abstraction but the times called for abstract expressionism and she couldn’t find a gallery. Even a woman-owned gallery turned her work down — because she was a woman.

A short excursion into the life of a committed artist is always great to take. This film gives you a lot to chew on. Alison Klayman, by the way, is the director of the documentary, AI WEIWEI: NEVER SORRY (2012).

See the trailer for each movie here at the Film Forum website. Also at the link, check out the ancillary programs with the directors talking about the films.

An exhibition of Murray’s work, curated by Carroll Dunham & Dan Nadel, is on view through January 29 at CANADA (333 Broome Street, NYC).

Carmen Herrera’s solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum closes Jan. 9, 2017. See excerpts from the movie at the Whitney website link.

EVERYBODY KNOWS…ELIZABETH MURRAY and THE 100 YEARS SHOW will play for one week only, January 11 – 17, 2017, at Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street (West of 6th Avenue), with screenings daily at 12:30, 2:30, 4:40, 7:00, and 9:10.