“Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.”

— Gabriel García Márquez, from Living To Tell The Tale

The Story of a Nonagenarian, Indefatigably Industrious, Japanese Hawaiian American

In snippets filmed over six years and woven into a documentary over another three, filmmaker Kimi Takesue presents 95 AND 6 TO GO, a look into the last years in the life of her very appealing, widowed, nonagenarian grandfather, Tom Takesue, an American of Japanese descent who was born and raised in Hawai’i. The film records scenes from Mr. Takesue’s daily life in Honolulu, interwoven with snapshots from his past and of his family, including formal photographs of earlier generations of his ancestors in Japan, and glorious panoramic scenes of Hawai’i, particularly of the sea, which plays such a powerful role in the consciousness of all Hawaiians.

For reasons not disclosed in the film, but perhaps suggesting a stereotype of Japanese reticence, during the six years of filming, Mr. Takesue warned his granddaughter that he would not permit her to publish the film –- and it was not until the end of his life that he relented. Indeed, after he changed his mind, he came up with the title of the film, analogizing from his interest in football — he was 95 when diagnosed with an illness, and learned that he had only 6 months to live. 95 AND 6 TO GO.

The film is a portrait of an elderly man who is indefatigably industrious. We see him attending to his laundry, doing push ups and exercises designed to improve his posture, clipping coupons and ads from magazines, rummaging through stuff in his cluttered house, fixing, puttering, tinkering, weeding out unwanted items and throwing them away, watering flowers, and eating, and eating again. The man is astonishingly focused, busy and self-sufficient, and he seems fully engaged in the tasks that fill his daily life, tasks which he tackles with determination, perseverance and endurance, and without complaint.

A man of many facets

The film also includes Mr. Takesue’s recollections and comments, usually recounted in response to questions posed by his granddaughter who, but for one hug (and perhaps one other scene), remains behind the camera, and who is intent upon eliciting her grandfather’s memories, dreams and reflections.

Tom Takesue comes across as a man of many facets, including various contradictions and eccentricities. He is blunt, unsentimental, and apparently even unfeeling at times. There is a deadpan quality to his manner. Sometimes he seems taciturn, and at others he is remarkably endearing and humorous. It is usually not evident how the man feels, even when he is relaying stories packed with pathos. When his granddaughter asks him about the death of one of his own children, a daughter who died in an accident at the age of 33, for instance, he replies, with a surprising degree of stoicism, that one must go on living.

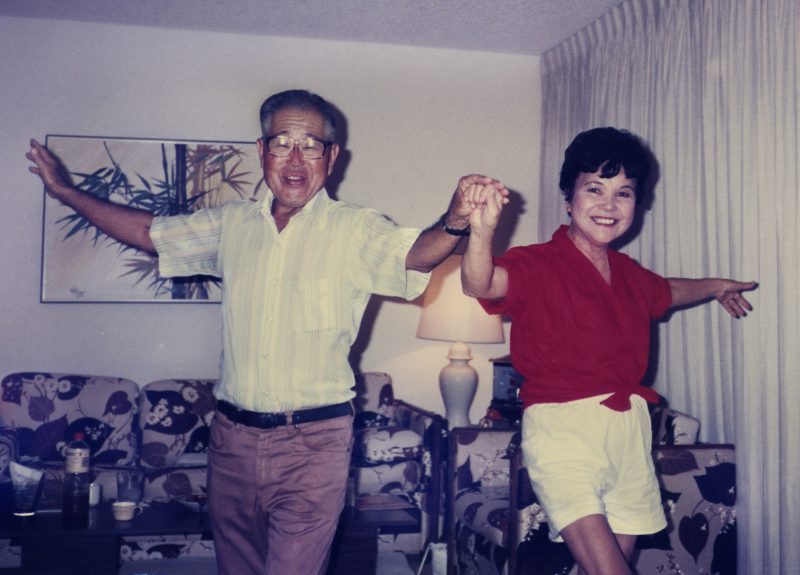

You also get a picture, at least obliquely, of Mr. Takesue’s marriage. When his granddaughter asks him about meeting and courting his wife, his story suggests that it was an arrangement. Later in the film, his late wife makes a cameo appearance and tells a very different story, remembering his romantic pursuit of her. Although he clearly misses his wife – there appears to be an ancestral shrine that includes his wife, and he visits and cares for her grave – he also criticizes her. He was a lover of movies, and he comments that his wife had a habit of falling asleep during them.

There is a poignant and delightful scene in the film when Mr. Takesue talks of his desire to find a new companion, someone who also might take care of him. When his granddaughter volunteers for the job, he rejects the proposition out of hand, and goes on, with affectionate gruffness, to tell her that she is wasting her life writing screenplays, and presumably filming him, and he advises her to get a real job.

There also is a wonderful scene in which he is diligently cutting out coupons and ads from magazines, and his granddaughter inquires why he has cut out one for wallet brassieres. He ignores her.

Discovery of the man’s creative and romantic side

Finally, we see another side of the man, perhaps one foreshadowed by his love of movies, as well as dancing. To his granddaughter’s surprise, and delight, Mr. Takesue becomes engaged in a screenplay that she had been writing, apparently a love story. In what seems like an unleashing of latent creativity and romanticism, he studies the script, suggests a title for it (The Bridge of Love), and a new (happier) ending. Indeed, there are a number of fantastic scenes in which Mr. Takesue suggests songs for the script, and in one, he unselfconsciously sings part of “You Were Meant For Me,” from Singing in the Rain.

Why we should care about Tom Takesue

Although hardly without challenges, Tom Takesue lived a prosaic life, and it is remarkable to witness his imperfections, his indomitable spirit, and to get a glimpse of his inner passionate nature. It’s really impossible to walk away from the film without admiration for the man, and a conviction that beneath his sometimes brusque exterior was a soft side, and a love of living.

There is also, of course, the moving connection between grandfather and granddaughter, and her preservation of memories about him, and of his stories – revisionist and otherwise — which are embedded in the film. The film ends with Mr. Takesue’s death, and one feels grateful that not all of his stories and recollections are left to accompany him to the grave. Those of us whose parents and grandparents are still living are well advised to follow in Kimi Takesue’s footsteps and to discover, and in some way to memorialize, the stories of their lives.

At the end of the day, I wonder whether, and if so why, the rest of us should care about Tom Takesue. I do. I do because the film captures the breadth of the man’s humanity, and it left me feeling privileged that in this small way our lives have touched. I do, because I understand that the bell tolls for us all.

Kimi Takesue is a recipient of the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship. Her films have screened extensively at festivals and museums, including Sundance, New Directors/ New Films, Locarno, Rotterdam, SXSW, the Walker Art Center, and the Museum of Modern Art. She is a graduate of Temple University’s MFA program and currently is an Associate Professor in the Department of Arts, Culture, and Media at Rutgers University.

I saw 95 AND 6 TO GO at the International House Philadelphia, in the Scribe Video Center, as part of the Scribe Producer’s Forum. Keep your eyes out for an opportunity to see this impressive, heartwarming documentary.