Harlem was where Roberta and I started out yesterday on our trip to the Big Apple. With a mixture of admiration and disappointment, we noted that 125th Street looks like Main Street these days, with H&M and Starbucks, etc. etc.

Harlem was where Roberta and I started out yesterday on our trip to the Big Apple. With a mixture of admiration and disappointment, we noted that 125th Street looks like Main Street these days, with H&M and Starbucks, etc. etc.

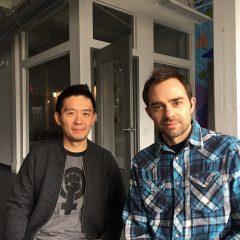

What brought us to Harlem, was “Black Belt” at the Studio Museum in Harlem, a show about how Asian martial arts and culture, especially via kung fu movies with black combatants, have influenced African-Americans. The 19 artists in the show, many of them familiar names like David Hammons, Ellen Gallagher and Paul Pfeiffer, contributed work that alluded not only to Kung Fu but to anime, video games and Asian decorative motifs.

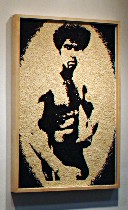

A couple of pieces honored kung fu movie hero Black Belt Jones, played by Jim Kelly. Sanford Biggers’ Black Belt Jones (shown), at the entry to the show, is made of Indonesian black rice and white rice glued to paper, with only the black portions expressing the image, the white areas melting into the white background.

And his “Nanchakus,” two braided lucite clubs connected by a gold chain and lit up from inside with a red light, transform the simple Asian fighting sticks into pure bling-bling (I swore I would never use that word, but there it is), showcased in a glass case as is all the finest jewelry.

Not all the cultural merging has been met with open arms. The artists responded to the invasion of Asian martial arts culture into their neighborhoods and into their own African-American culture with resentment as well as pleasure.

Not all the cultural merging has been met with open arms. The artists responded to the invasion of Asian martial arts culture into their neighborhoods and into their own African-American culture with resentment as well as pleasure.

Glenn Kaino’s video game, “Game of Death,” made in collaboration with Mark Bradford, and based on the Bruce Lee-Kareem Abdul-Jabbar kung-fu movie of the same name, was a homage. But Patti Chan’s pieces, “Death of Game,” were critical, especially of how white Hollywood kept their own hands clean by pitting the two non-whites against one another. (Jabbar lost the fight.) The movie, Bruce Lee’s last, inspired a number of pieces in the show (shown, Kaino’s sculpture Bruce Leroy).

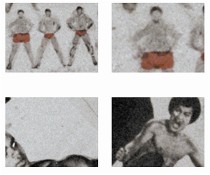

Of Ellen Gallagher’s several 6-minute, 16-millimeter films, made in collaboration with Edgar Cleigne, my favorite was “Murmur: Monster Movie,” in which the aliens (wearing scratched-on-the-film, bobbing Andy Warhol fright wigs) threaten to take over the local folks . The silent film, with text from corny sci-fi movies, raises questions about which aliens are threatening which culture. Another by Gallagher, Murmur: Super Boo,(some frames shown), creates a black superhero with the help of old comic book ads for building the he-man look, plus a little Bruce Lee, Muhammed Ali and voila.

Of Ellen Gallagher’s several 6-minute, 16-millimeter films, made in collaboration with Edgar Cleigne, my favorite was “Murmur: Monster Movie,” in which the aliens (wearing scratched-on-the-film, bobbing Andy Warhol fright wigs) threaten to take over the local folks . The silent film, with text from corny sci-fi movies, raises questions about which aliens are threatening which culture. Another by Gallagher, Murmur: Super Boo,(some frames shown), creates a black superhero with the help of old comic book ads for building the he-man look, plus a little Bruce Lee, Muhammed Ali and voila.

Paul Pfeiffer’s tiny (maybe 3 inches wide) 20-second video loop, “Live Evil,” shows a headless Michael Jackson moonwalking as his upper body morphs into a rorschach-like mandala, making him at once robotic and insect like. I’m not sure of the Asian connection here, but I liked it. Asian video equipment?

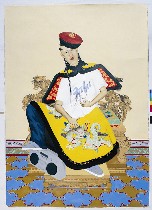

My favorite pieces were Iona Rozeal Brown’s hip-hopsters gone Japanese(shown, a would-be emperor). The images are elegant, Brown’s eye for telling details sharp. She skewers her subjects by their own pretensions.

From there, Roberta and I headed downtown to the Whitney for John Currin’s own brand of social skewering. But that’s another post.