Roberta and I headed toward what we hoped was not the swan song for the stellar international art events that Moore College of Art has been holding over the years.

Roberta and I headed toward what we hoped was not the swan song for the stellar international art events that Moore College of Art has been holding over the years.

The show at Moore is “Jorg Immendorff: I Wanted to Become an Artist,” curated by Robert Storr and Pamela Kort. It’s the first solo museum exhibition of this 58-year-old German artist’s work in the United States.

And to kick it off, Moore presented a symposium Friday that attracted about 80 intense art lovers, willing to fork over the $20 and listen to a lot of talk about one guy.

What a great panel, with five people who came at the material with such different approaches.

What a great panel, with five people who came at the material with such different approaches.

Besides Storr (former senior curator in painting and culture at MOMA and now a chaired prof at NYU) and Kort (curator and art historian as well as author of a book on Immendorff), the panel included Arthur C. Danto (philosopher and art critic for The Nation), Isabelle Moffat (Hamburg-based art historian with lots of Immendorff creds), and artist and critic Stephen Ellis (who has written extensively about German art of the ’80s) (shown left to right, Moffat, Danto, Ellis, Storr and Kort).

(The show, by the way, is tops and we’ll weigh in on it later.)

Here are a few of the highlights of the symposium, “Jorg Immendorff: Arguments with the Present; Conversations with the Past,” which focused on the contradictions within Immendorff’s art (shown, “Setting Germany in Order”). Otherwise I’m hard-pressed to synthesize in any way:

Here are a few of the highlights of the symposium, “Jorg Immendorff: Arguments with the Present; Conversations with the Past,” which focused on the contradictions within Immendorff’s art (shown, “Setting Germany in Order”). Otherwise I’m hard-pressed to synthesize in any way:

Some comments from panel moderator Storr:  Immendorff shares with Anselm Kiefer and Gerhart Richter the impulse to excavate the German past (shown, Richter’s portrait of an American Phantom jet), exemplified in Immendorf’s “Cafe Flore” painting, which includes a portrait of Max Ernst, who represents German culture lost during the Nazi era. (Storr later said that Immendorff says the people in his work are not about theory, so portraits of disparate artists like Francis Picabia and Ernst and Marcel Duchamp and Georgio de Chirico in one painting is not an embrace of their contradictory artistic practices.)

Immendorff shares with Anselm Kiefer and Gerhart Richter the impulse to excavate the German past (shown, Richter’s portrait of an American Phantom jet), exemplified in Immendorf’s “Cafe Flore” painting, which includes a portrait of Max Ernst, who represents German culture lost during the Nazi era. (Storr later said that Immendorff says the people in his work are not about theory, so portraits of disparate artists like Francis Picabia and Ernst and Marcel Duchamp and Georgio de Chirico in one painting is not an embrace of their contradictory artistic practices.)

Whereas U.S. art in the 1980s split in two threads, neo-expressionism and the conceptual sons of Marcel Duchamp, Immendorff unites the two traditions, as “an artist of ideas” who uses emotional self-expression.

Some comments from Kort: Immendorff, an iconoclast and a follower of Joseph Beuys, adopted Beuys’ pose as the “solo, pantomime artist” genius (his paintings often including himself as an actor in history).

Some comments from Moffat: Immendorff’s mixing of the personal and the political, a la Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp and Beuys, has influenced younger German artists, and his use of ugliness in his painting is “a safeguard to keep from being too comfortable” (shown, “Rake’s Progress”).

Some comments from Moffat: Immendorff’s mixing of the personal and the political, a la Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp and Beuys, has influenced younger German artists, and his use of ugliness in his painting is “a safeguard to keep from being too comfortable” (shown, “Rake’s Progress”).

Some comments from Stephen Ellis: Immendorff’s work presents unresolved paradoxes–more than one point of view within a single work. “It had to do with the political split in Germany, the post-war division,” and it allows the viewer to delay interpretation, following the artist’s train of thought.

Some comments from Arthur Danto: In Germany, unlike in the U.S., painting is a political act. Immendorff’s buddhistic babies of all races (see image at top of post) reflect a concern with being an artist without being an artist, i.e. being a pure infant, “a way of being, not thinking.” To Immendorff, Danto said, “the enemy of painting is the painter’s best friend–to paint badly.”

In the United States, art was about creating good art within the traditions of art history, cut off from life and politics, whereas “Germans are interested in something deeper, darker and more mysterious.”

In the United States, art was about creating good art within the traditions of art history, cut off from life and politics, whereas “Germans are interested in something deeper, darker and more mysterious.”

Discussion:

Disagreeing with Danto, Ellis said that German artists weren’t interested in killing the forms of the past but in “kicking [them] so something else comes out.”

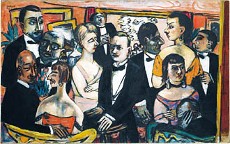

This comment led to a discussion of the ugliness in Immendorf’s work. An aesthetic of ugliness is in the tradition of German art history, said Kort, as well as a belief in the will of the artist to form art. She cited Adolf Wolfli and Max Beckmann as part of this tradition (shown Beckmann’s “Paris Society”).

This comment led to a discussion of the ugliness in Immendorf’s work. An aesthetic of ugliness is in the tradition of German art history, said Kort, as well as a belief in the will of the artist to form art. She cited Adolf Wolfli and Max Beckmann as part of this tradition (shown Beckmann’s “Paris Society”). Moffat raised the contradictions implicit in Immendorff’s collective town, Lidl, and how his politics of collective dialog (Immendorff was a communist) stood in the way of his ambitions to be recognized “He fears his identity will be erased by the politics,” she said (shown, untitled).

Moffat raised the contradictions implicit in Immendorff’s collective town, Lidl, and how his politics of collective dialog (Immendorff was a communist) stood in the way of his ambitions to be recognized “He fears his identity will be erased by the politics,” she said (shown, untitled).Storr enlarged on this idea, saying Immendorff assumes the persona of naivete. He provokes and expects resistance, yet he’s looking for allies and adulation as he does so.

Danto further enlarged: “He had perfect pitch for the infuriating gesture.” Somehow, this ability to poke instigated the German police to raid Lidl. “It’s like raiding the dollhouse,” Danto added.