Hanna Hannah’s show “Aftermath/Afterimage” on destruction and danger and loss at Schmidt/Dean does not transform terrible obsessions into beauty, but it does transform them into compelling—and ultimately strange–art.

I saw the work a month ago (it’ll be up until Jan. 10), and wasn’t sure what I wanted to say about it, so it’s been marinating and following me around in my mind. I don’t think I’m going to forget these images.

In two suites of paintings Hannah takes sallies at the same image over and over again.

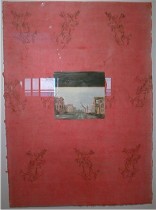

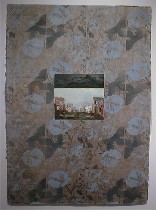

In the Taking of Grozny Series, she roughly paints a photograph she saw of the war-torn city over a background of mulberry paper, beautifully tinted and delicately painted with wallpaper-like repeating patterns that speak of the pleasures of a safe, domesticated world—animals for the kids’ rooms, flowers for the dining room, birds in the trees for the hall, etc. The domesticity and beauty and order of the paper stand in contrast to the central painting, a roughly brushed center of oily anger topped by a black stripe opening into a heart of darkness.

In the Taking of Grozny Series, she roughly paints a photograph she saw of the war-torn city over a background of mulberry paper, beautifully tinted and delicately painted with wallpaper-like repeating patterns that speak of the pleasures of a safe, domesticated world—animals for the kids’ rooms, flowers for the dining room, birds in the trees for the hall, etc. The domesticity and beauty and order of the paper stand in contrast to the central painting, a roughly brushed center of oily anger topped by a black stripe opening into a heart of darkness.

The safe domesticity of the background is shattered by the war outside. The colors of the central photo change from painting to painting–a response to the domestic border. The pieces are decorously framed behind glass and hung around the room nicely spaced.

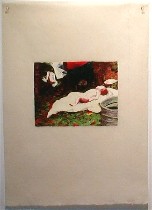

The other suite, Kindertotenlied (Song for Dead Children), are small paintings on large sheets of plain rice paper tacked to the wall in a tight grid. Again the painting is a roughly brushed center of pain, the colors jarring in the face of death–a dead child, laid out on a white cloth, a washtub in the right foreground (perhaps where the body was bathed for burial), the background perhaps adults kneeling and standing over the baby, their heads and hearts cut out of the painting.

The other suite, Kindertotenlied (Song for Dead Children), are small paintings on large sheets of plain rice paper tacked to the wall in a tight grid. Again the painting is a roughly brushed center of pain, the colors jarring in the face of death–a dead child, laid out on a white cloth, a washtub in the right foreground (perhaps where the body was bathed for burial), the background perhaps adults kneeling and standing over the baby, their heads and hearts cut out of the painting.

The baby looks doll-like and everything is a little hard to read, just like the death of one so young. Each picture includes a slightly different amount of background and foreground (in this series the colors are pretty much unchanging) but none of the paintings brings the image into a focus that can make sense of the terrible truth.

Hannah, a survivor of World War II who escaped to South America, keeps returning to the loss, the pain, the paintings like a tongue seeking out a missing tooth, over and over again.