I’m always interested in art as a window into the society that spawned it. These days, after listening to people snarl about Warhol and Duchamp(can you believe poeple are still snarling about them?), I’ve been thinking about our society that churns out people in anonymous multiples and that requires people to keep their real selves under p.c. wraps. It’s a society that spurns dissent and individuality and thinking, and glorifies commercialism (yesss, Andy; you go, Marcel) (shown, Warhol’s “Marilyns”).

Art as a window into society drew me to a talk at PAFA (the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), Wednesday, by Penn Professor of English and art lover Peter Conn on the urban paintings of Edward Hopper and his times (shown, “Sunday”).

Art as a window into society drew me to a talk at PAFA (the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), Wednesday, by Penn Professor of English and art lover Peter Conn on the urban paintings of Edward Hopper and his times (shown, “Sunday”). Hopper’s an easy sell, both to the curmudgeonly world of anti-Duchampians and contra-Warholians and the post-Ab-Ex crowd. Conn pointed out the line that snaked around the block for admission to the last Hopper show he attended.

I was there for the history plus a little time to think about what Hopper was doing in his paintings.

Hopper began painting in the midst of a major social upheaval, the change of the United States into a post-agrarian, post-frontier society. How’re you gonna keep ’em down on the farm? You’re not. Between 1890 and 1920, Conn said, the census shows an enormous shift of population from the “scarcely populated agrarian world of the 19th century” into the cities (shown, “Eleven a.m.”).

Hopper began painting in the midst of a major social upheaval, the change of the United States into a post-agrarian, post-frontier society. How’re you gonna keep ’em down on the farm? You’re not. Between 1890 and 1920, Conn said, the census shows an enormous shift of population from the “scarcely populated agrarian world of the 19th century” into the cities (shown, “Eleven a.m.”).And the shift meant the loss of traditional family ties and a rootlessness. Hopper’s cityscapes from the 1920s and ’30s were less about the bustling crowd and more about isolation and rootlessness. Conn said that Hopper made four paintings with “hotel” in the title.

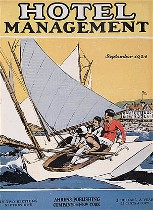

My favorite Hopper tidbit was learning that he was employed by “Hotel Management” magazine to create drawings (here’s one of his covers), which Conn characterized as “carefree icons of fake happiness.” Perhaps, Conn suggested, Hopper’s claustrophobic hotel room paintings were his revenge on his earlier employement.

My favorite Hopper tidbit was learning that he was employed by “Hotel Management” magazine to create drawings (here’s one of his covers), which Conn characterized as “carefree icons of fake happiness.” Perhaps, Conn suggested, Hopper’s claustrophobic hotel room paintings were his revenge on his earlier employement.

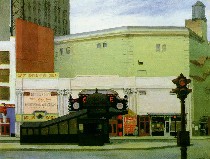

On Hopper’s “Circle Theater” (shown): “He chose a subject he does not let us see,” said Conn, pointing out how the subway kiosk nearly obliterates the theater marquee and entrance.

On Hopper’s “Circle Theater” (shown): “He chose a subject he does not let us see,” said Conn, pointing out how the subway kiosk nearly obliterates the theater marquee and entrance.

Among other Hopperisms that Conn noted were the lack of horizon line, the windows without doors and doors without handles–a claustrophobic world of isolation (shown, “Nighthawks”). Plus they’re scenes that leave room for the viewer to make up stories about what has happened and what will happen.

Among other Hopperisms that Conn noted were the lack of horizon line, the windows without doors and doors without handles–a claustrophobic world of isolation (shown, “Nighthawks”). Plus they’re scenes that leave room for the viewer to make up stories about what has happened and what will happen.

I’m stopping here with no big conclusion, but just to say I enjoyed the info, and here’s a picture of Duchamp’s “Fountain,” which represented the same societal upheaval in a different way.

I’m stopping here with no big conclusion, but just to say I enjoyed the info, and here’s a picture of Duchamp’s “Fountain,” which represented the same societal upheaval in a different way.

This was part of PAFA’s art-at lunch series. The next one is Feb. 28, American Abstraction in the Cold War Era–Reconsidering the Categories “Conservative” and “Radical”–Focusing on the artists included in the Academy’s exhibition Radicals and Conservatives: Abstraction 1945 to the Present, Dr. Sarah K. Rich, assistant professor of art history at Pennsylvania State University, will discuss how it is now historically possible to decide upon the political motivations and effects of abstract art in the Cold War Era.