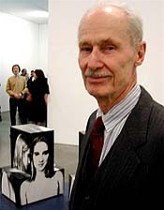

I don’t think Richard Artschwager (shown in a photo from 2002, and see Feb. 12 post) really wanted to address the crowd that filled every seat in the ICA’s auditorium and lined the walls and the floor.

He was nervous, and his age had taken a toll on his focus, especially at the beginning of the conversation. A tall, slim man in 3-piece suit, somehow he looked less like a banker or lawyer who was trying to look professional and powerful, and more like my childhood neighborhood pharmacist who was trying to disappear behind his correct clothes–his clothes somewhat like the patina of formica on some of his sculptures.

But he was surrounded by people who seemed to care for him. They treated him kindly.

ICA Senior Curator Ingrid Schaffner, who had worked as his archivist, teased him gently as she listed his accomplishments. She recalled how she had his years of unopened mail to sort through, some of the envelopes bearing poignant notes begging Artschwager to please, please open this particularly urgent piece of mail. Here, again, I got a picture of somewone who wasn’t all that eager to interact with strangers (shown right, “Time Piece,” by Artschwager”).

ICA Senior Curator Ingrid Schaffner, who had worked as his archivist, teased him gently as she listed his accomplishments. She recalled how she had his years of unopened mail to sort through, some of the envelopes bearing poignant notes begging Artschwager to please, please open this particularly urgent piece of mail. Here, again, I got a picture of somewone who wasn’t all that eager to interact with strangers (shown right, “Time Piece,” by Artschwager”). And former ICA Director Suzanne Delehanty, who gave Artschwager his first solo museum show at the ICA, never stopped smiling and nodding her head in encouragement, even when his answers didn’t exactly answer the original question. Affectionately, she came back at him again, with her original query, “But what about perspective, Richard?” (Shown, an untitled “box” by Artschwager)

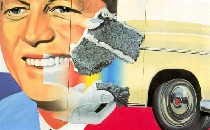

And former ICA Director Suzanne Delehanty, who gave Artschwager his first solo museum show at the ICA, never stopped smiling and nodding her head in encouragement, even when his answers didn’t exactly answer the original question. Affectionately, she came back at him again, with her original query, “But what about perspective, Richard?” (Shown, an untitled “box” by Artschwager) Once Artschwager became focused enough to answer the questions, he chose metaphorical explanations. Asked about the frames in his work, he answered that others were making big paintings that filled the field of vision, thank to the GI Bill and the surging economy and artist access to huge lofts. (A couple of days later, I read a James Rosenquist Q&A in Art in America in which he said that his paintings grew bigger as his studio space grew. Shown, a large Rosenquist, uninhibited by a frame.) So Artschwager said he went in the other direction and put frames around his work.

Once Artschwager became focused enough to answer the questions, he chose metaphorical explanations. Asked about the frames in his work, he answered that others were making big paintings that filled the field of vision, thank to the GI Bill and the surging economy and artist access to huge lofts. (A couple of days later, I read a James Rosenquist Q&A in Art in America in which he said that his paintings grew bigger as his studio space grew. Shown, a large Rosenquist, uninhibited by a frame.) So Artschwager said he went in the other direction and put frames around his work.

Somehow, that explanation seemed to fit the character of the man who sat before the crowd, framed by his dark blue suit, his shirt and tie. Neither the “explanation” nor the clothes revealed much about what Artschwager, who worked some of his life as a carpenter, was really thinking.

I don’t know how he and Delehanty were able to sit comfortably up on the platform, their two chairs free-floating on either side of a glass table, no protective desk or table to lean on or to hide behind. Delehanty, dressed in a knee-length brown dress that draped loosely at the hem, was able to somehow arrange herself gracefully and modestly. Artschwager, 80, sat straight in his chair.

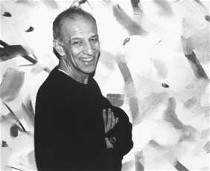

This put me in mind of the Robert Storr-Alex Katz talk at Penn last year. They too were exposed, but Katz (shown left) lounged comfortably where he sat, wearing drapey, rich-looking clothing–silk?, fine leather shoes, and although he’s just three or four years younger than Artschwager, he projected a graceful, aggressive physicality and empowerment that matched the social milieu he often paints and the gestural quality of his nature paintings. Katz wanted you to notice what a guy he was.

This put me in mind of the Robert Storr-Alex Katz talk at Penn last year. They too were exposed, but Katz (shown left) lounged comfortably where he sat, wearing drapey, rich-looking clothing–silk?, fine leather shoes, and although he’s just three or four years younger than Artschwager, he projected a graceful, aggressive physicality and empowerment that matched the social milieu he often paints and the gestural quality of his nature paintings. Katz wanted you to notice what a guy he was.

Artschwager, whose art work is highly conceptual, did not want to give too much of himself away. He wanted you to look at the art and look some more until it became meaningful to you. Explanations, he felt, were not his friends. At the same time that he held back, he was hoping you’d notice how smart, insightful and funny he was.