I got my first taste of “The Big Nothing” yesterday at the “Responsa: Eileen Neff, Jennie Shanker, and Richard Torchia” exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art–the small art gallery on North Broad Street in Congregation Rodeph Shalom.

“The Big Nothing,” if you don’t know what I’m talking about, is an ICA-organized, city-wide series of art shows with the theme of nothingness. In addition to an exhibit of heavy hitters at the ICA, opening to great fanfare this weekend, there are 36 other venues around town that are putting forth their own takes of artistic expressions of nothingness during the next three months, and you need a map. Oh, there is a map. It’s cute as pie (produced by alt-art practitioners Andrew Jeffrey Wright and Thom Lessner), a part of a key-lime green guide that took me 45 minutes to get through.

But putting the big picture aside (Roberta’s previous post, by the way, is also about the Big Nothing), the show at the PMJA had some interesting takes on nothingness in the three installations on display.

Digi photographer Eileen Neff’s 7-foot tall (my guess) view of the synagogue pews, framed by a faux archway to suggest a view through a door, suggests the people who sat, sit, and will sit in those spaces. It also suggests with its stretched perspective and its edge-to-edge, top-to-bottom nothing-but-pews an infinity of pews ascending to heaven in step-like progression. The light glancing off the pew backs is exaggerated just enough to suggest some heavenly magic and some presence of souls here on earth. Neff’s piece manages to provide both visual satisfaction and a rich world of metaphors.

Jennie Shankar’s griddy “Mortar,” which almost divides the gallery space in two, is a minimal metal framework, a drawing in air, delineating the mortar that used to hold the stones in place on the synagogue’s original Frank Furness building. To put it another way, the stones are not there, only the pattern of the mortar, front and back. The original building is gone, replaced in the 1920s by the current building.

Jennie Shankar’s griddy “Mortar,” which almost divides the gallery space in two, is a minimal metal framework, a drawing in air, delineating the mortar that used to hold the stones in place on the synagogue’s original Frank Furness building. To put it another way, the stones are not there, only the pattern of the mortar, front and back. The original building is gone, replaced in the 1920s by the current building.

The references here are to the absence of not only the original synagogue building, but also the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem. To see this piece is to think Wailing Wall, and to miss something no longer there. But it’s also to recognize and glorify the role of the mortar — or something that’s so visually subsidiary that it’s almost invisible — in keeping the stones together, which in turn suggests a parallel to a religion (the mortar) and its people (the stones). Anyone familiar with the ritual of the Passover seder has thought about mortar, but maybe not quite in this way.

The antithesis of materiality of mortar is Richard Torchia’s “Busted Rainbow,” which uses colored gels to transform the recessed fluorescent lights that illuminate the gallery’s barrel vault into a rainbow–the biblical sign of a promise to Noah from God to never flood the world again. The suggestion that a promise from God has been broken or is no longer there opens the way to any number of interpretations, depending on your personal obsessions about the state of the world and your personal take on whether God is an absence, a presence, or a big nothing.

The antithesis of materiality of mortar is Richard Torchia’s “Busted Rainbow,” which uses colored gels to transform the recessed fluorescent lights that illuminate the gallery’s barrel vault into a rainbow–the biblical sign of a promise to Noah from God to never flood the world again. The suggestion that a promise from God has been broken or is no longer there opens the way to any number of interpretations, depending on your personal obsessions about the state of the world and your personal take on whether God is an absence, a presence, or a big nothing.

When I came to see the show, which was curated by Matt Singer, one of the women in the office looked at me speculatively and asked me if I knew what to expect. After that intro, I expected a big nothing. But the three pieces all offered up something, to varying degrees.

The same woman asked me to mention the hours: Mondays to Thursdays, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Friday, 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., but please call first, 215-627-6747.

P.S.: The introductory information on the wall explains the meaning of responsa: a system whereby individuals’ questions about life and faith are answered by rabbis. The system, still in practice, dates to the Third Century, and the Q&As then become a kind of commentary referred back to by later rabbis.

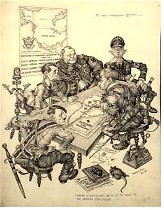

P.P.S. Which brings me to “Sonja’s Legacy” at Drexel University’s library, billed as an art show but in fact really a memorial to Sonja Fischerova, a young girl who died at Auschwitz, leaving behind her drawings and paintings as her legacy. This is not a Big Nothing show, but it’s about absence and loss. The work, though childish, has some chilling images–once you read the explanation–and the exhibit, which includes only facsimiles of her art work as well as examples of other anti-Nazi literature and art work (including a couple of outstanding political cartoons by Arthur Szyk)–was moving, personal, and historical.

P.P.S. Which brings me to “Sonja’s Legacy” at Drexel University’s library, billed as an art show but in fact really a memorial to Sonja Fischerova, a young girl who died at Auschwitz, leaving behind her drawings and paintings as her legacy. This is not a Big Nothing show, but it’s about absence and loss. The work, though childish, has some chilling images–once you read the explanation–and the exhibit, which includes only facsimiles of her art work as well as examples of other anti-Nazi literature and art work (including a couple of outstanding political cartoons by Arthur Szyk)–was moving, personal, and historical.