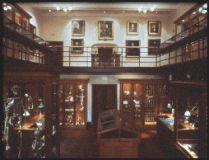

The second half of our Tuesday double-bill of openings took place at the Mutter Museum, the historical collection of the American College of Physicians with medical specimens related to diseases and aberrations of the body.

The second half of our Tuesday double-bill of openings took place at the Mutter Museum, the historical collection of the American College of Physicians with medical specimens related to diseases and aberrations of the body.

The show is “9 Mutter XX04,” part of the Big Nothing festival and it’s got a world-class lineup of art stars including Karen Kilimnik, Jesse Olanday, Olaf Westphalen and Thomas Zummer.

The Mutter, if you haven’t been, is a destination in and of itself, its skeletons (conjoined twins, a giant), collection of skulls, wax mock-ups of gangrenous body parts, disease samples in jars and more are memorable to say the least. (image is Zummer’s “Drawing of a Photograph of a Misregistered 16 mm Frame of an Edison paper Print, circa 1906,” and notice the collection of skulls reflected in the piece’s glass)

Anyway, so you’ve got these tremendously gripping human disease samples in ceiling to floor glass cases on two floors. Where are you going to put the art and how will it stand up in this environment?

Those were two scientific questions Libby and I were interested in as we looked around. (image above is Kilimnik’s “Spring Zephyr” and “Summer Zephyr,” dreamy and candy-like sky paintings. Sorry about the yellowness, my bad.)

The answer to where was to place the art quietly here and there — on the few bare walls and sprinkled around inside the glass cases. It turned the exhibit into a kind of treasure hunt. Luckily there’s a map. (image is Francois Bucher’s installation in the case with the plaster casts of Cheng and Eng, the original Siamese twins)

Interestingly, the whole thing puts the Mutter collection in an art context, which, if you think of the Chapmans aberrant body sculptures and Damien Hirst’s formaldahyde shark tanks, is not a bad call. Needless to say, the art was washed in the Mutter’s atmospherics.

And for the most part, the art stood up to the collection, commenting on it or commenting on other unusual phenomena with existential overtones. Westphalen’s large untitled cartoon, placed in a spot so it looked like a bus shelter advert, is a great example of dark humor in a disease context. You can’t read the image but it’s of a doctor and patient in an examining room. (image above)

Doctor says: Instead of a prescription, I’ll write you a check for 5 million dollars.

Patient says: Great! I feel better already. Maybe poverty is a disease after all.

I did think Jesse Olanday’s silkscreen poster placed in the case near the skeleton of the fetal conjoined twins felt transgressive. (shown, Olanday’s “Allison’s Ode to Nothing”)

There’s a sacred feel to this place — all the bones and real body parts turn it into a graveyard exposed. And Olanday’s piece had a rock poster sexiness and seeming irrelevence to its surroundings that was jarring.

Because the work’s interwoven with the collection, it’s easy to get confused about which is which. And with all the reflective glass surfaces, the art and collection were married anyway with reflections of one on the other all over the installation.

One piece that stood out and stood alone was Ulrike Mueller’s audio installation (shown) “One of Us (Freakish Moments)” in which you hear a woman, in German-inflected English, tell graphic stories of bodies and minds in extremis. Heavy with detail and, if memory serves, told in “you are there” first person accounts, the piece is a stomach churner. It’s impossible to miss because of its red velvet drape.

I actually mistook one of the Mutter’s own objects (a crocheted doily made by a blind woman, not shown) for a contemporary artwork at one point, which was funny and not a little freaky to me.

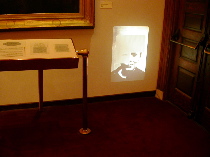

Peter Lasch’s “Naturalizations: The Mechanism of Facial Expression,” perhaps the weakest entry, was a science museum piece about facial characteristics. The three-part piece included a slide show (shown) projected near the floor for some reason; a group of photocopies of faces you could handle and plexiglas boards with holes for eyes and mouth and with mirrored surfaces to obscure part of the face. (shown, Libby posing with one of the glass/mirror boards) The exercise seemed silly and obvious.

Basically, the show’s pretty good and its sense of exploration and dark humor is appropriate to the institution. I am trying to imagine this show in a different location and can’t quite. Somehow, a white box with all this work might be a bust.

Now for some gossip. Libby and I saw many familiar faces, some of whom trickled over from the Art Alliance opening. Artist Karen Kilimnick was there, along with her mother. We caught up with PAFA curator Alex Baker who told us about his new curatorial effort at DUMBO and about his recent surfing vacation at Cape May. Mark Shetabi was there, excited to be in the Mutter again (apparently he made a bunch of drawings there when he was a student.) Sarah Roche was there, sitting outside waiting for Mark, confessing she wasn’t in a Mutter mood.

Rob Matthews and Tracy popped in after his Art Alliance opening. Slought’s Aaron Levy and the Cultural Alliance’s John McInerney were caucusing about something or maybe it was nothing.

We also saw Paul Swenbeck and heard that PEI honcho Paula Marincola was there although we didn’t spot her. We chatted briefly with Eileen Neff who was having fun reading the 100-word sentence on a wall card for one of Thomas Zummer’s works. And Richard Torchia was outside the place when we were leaving, maybe with his bike, who remembers.

Finally, we introduced ourselves to Mutter Director, Gretchen Worden, who was happy to have her institution included in the Nothingness. She was decked out in basic art black and around her neck was a necklace that turned her into a walking specimen case. The necklace, a framed array of mouse bones set in a spiral configuration, was delicate, beautiful, and just the right amount of weird.