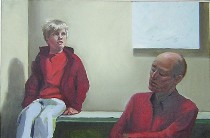

I stopped in at the Manayunk Art Center (for my first time ever) to see Nancy Bea Miller’s show “Only Human,” 33 oil paintings done over the past year, during the course of an Independence Foundation grant to paint all kinds of people, including those with disabilities (shown, “Waiting for the Specialist”).

I stopped in at the Manayunk Art Center (for my first time ever) to see Nancy Bea Miller’s show “Only Human,” 33 oil paintings done over the past year, during the course of an Independence Foundation grant to paint all kinds of people, including those with disabilities (shown, “Waiting for the Specialist”).

The interest grew out of her experience with one of her own children, who has a severe form of autism that includes mental retardation.

But what makes these paintings interesting goes beyond including the disabled in the lexicon of subjects we paint (shown, “Adjustment”). As in Miller’s still lifes (see Libby’s post), what seems most interesting is the way that people become objects that share physical space but do not necessarily share mental space. It’s the human condition of aloneness, not just for the disabled with their unique problems, but for all of us that give these paintings their power.

In “Three Boys,” Miller equates the chasms of emotional detachment with symbolic trees behind the children. Two are lollipop trees, and three and triangle trees. One boy stands totally separately, and one reaches out to another on the ground who doesn’t return much interest. In “Henry in the Kitchen,” the mug becomes a symbol for daily life as well as another person. Henry seems to be on his own there.

Miller also had a series of portraits (shown, “Michael and Lisa”), which seemed more conventional, although beautifully painted with nice light and monotone icon-like backgrounds. These seemed less interesting to me, more ordinary, narrower in their ambition–to unite all humans as suitable subjects for painting.