Post by Colette Copeland

On Tuesday, I took a mini road trip to Washington DC in order to make the morning press preview at the Corcoran Gallery of Art for the new Sally Mann exhibit, “What Remains.” I relish the luxury of viewing work without hoards of people and the opportunity to meet an artist whose work I admire.

“What Remains” is a comprehensive overview of Mann’s work from 2000-2002. The press release stated that “it was a five-part meditation on mortality, exploring the ineffable divide between body and soul, life and death, spirit and earth.”

I wondered if the work would hold up to the provocative photographs of her children, which caused Mann such notoriety. Now that her children are grown, she has turned to landscape?

I admit I was skeptical. However the promise of death and decomposing bodies intrigued me.

“Matter Lent” is a series of prints made from the 19th century wet plate collodion process depicting the year old excavated remains of the family’s beloved greyhound. (shown is “Untitled #17” 2000, a gelatin silver print with varnish from that series)

For the first time, the original plates were presented along with the prints. The plates had rich tones, a three-dimensional quality and depth, which the prints lacked.

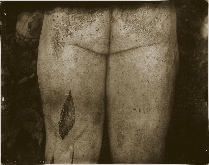

The series “Untitled” depicts decomposing bodies from the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Facility. What made the photographs so unsettling, was not that they depicted dead bodies, but the context and the aesthetic of the images.

I had expected the bodies to be in a sterile lab, not in a thickly forested area. By removing them from the context of ‘specimen,’ the images suggested that these forms were victims of horrific crimes, dumped for disposal. (shown is “Untitled #9” 2001 from that series, a gelatin siver print with varnish)

Additionally Mann creates a new aesthetic from an anti-aesthetic. The hand-applied emulsion and unpredictability of the process produces results which would make photographic formalists shudder. The prints were flat, dark and covered with stains, streaks, dust and rips. The images were not matted and framed as traditional photographs, but varnished and mounted like paintings. The technique created a veiling, which abstracted and beautified the subject matter. The mark making was key to the success of the series.

Mann continues with the aesthetic/anti-aesthetic in the “Antietam” series, which blurs the lines between painting and photography. By revisiting and photographing the site where 23,000 men were killed in September 1862, Mann questions photography’s relationship to history, place and time.

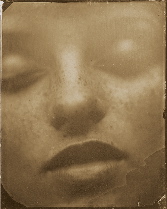

The exhibit ended with extreme close-up photographs of her children’s faces. (shown is “Untitled #11” 2000, an ambrotype from the series “What Remains”)

Again she showed both the original plates and some large prints. As with the dead greyhound images, the photographs did not hold up to the immediacy and sculptural quality of the plates. Mann chose to end with life, stating that “Death is approached as a springboard to appreciate life more fully.”

—Colette Copeland is an artist, teacher and regular contributor to artblog. Her performance group–The Women’s Art Rescue Squad will be part of the exhibit “Girl Art Now” at the Hera Gallery in Wakefield, RI. They’ll be performing at the opening this Saturday.