Pepon Osorio’s “Trials and Turbulence”, which opened at the ICA Friday, brings into the open a place where private lives are affected by public policy.

He takes over the first floor of the ICA with an installation that piles up realistic details, revealing the everyday lives of people. By putting the lives in the gallery space at a scale and level of detail that’s overwhelming, he is granting the issues in those lives a gravitas that makes a viewer pay attention.

The world he builds is a re-creation of the beaurocracy that handles foster children.

The world he builds is a re-creation of the beaurocracy that handles foster children.

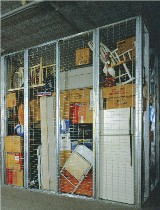

Every inch of the social workers’ cubicles (top) are decorated with photos and cheap gewgaws. An enormous cage is piled high with a family’s possessions–their tv, their furniture, their lamps, their clothes, their lives torn apart (right). The details are wrenching. The size of the pile is overwhelming. The bureaucracy and its cage is domineering.

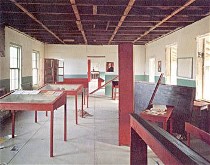

In contrast to these personal revelations, a reconstructed interview room stands in its institutional barrenness as the voice of a client answers a probing caseworker’s questions (left). The re-creation of a courtroom, in all its institutional splendor, includes a bathroom in a curio cabinet, the client stripped bare in front of her accusers (below left).

In contrast to these personal revelations, a reconstructed interview room stands in its institutional barrenness as the voice of a client answers a probing caseworker’s questions (left). The re-creation of a courtroom, in all its institutional splendor, includes a bathroom in a curio cabinet, the client stripped bare in front of her accusers (below left).

And then there’s a chance to consider the alternative. A dark, walled-off room of the gallery offers a space that’s outside the governmental system altogether. Constructed of wood salvaged from the streets of North Philadelphia, the wall allows a peek into a dark room and a video of a boy running away through the darkened streets (right).

And then there’s a chance to consider the alternative. A dark, walled-off room of the gallery offers a space that’s outside the governmental system altogether. Constructed of wood salvaged from the streets of North Philadelphia, the wall allows a peek into a dark room and a video of a boy running away through the darkened streets (right).I asked one of the guards, a woman I often chat with when I stop at the ICA, what she thought of the exhibit. She loved it and she recognized it. “Let’s put it this way,” she said. “I’ve been here before.”

But what Osorio does with the space is not just re-create. He creates an intersection, where the different actors whose lives are touched by the System can see each other’s point of view, can walk into each other’s spaces and feel safe.

Anyone can sit on the judge’s bench in Osorio’s courtroom and view the video, or look into the glass-enclosed bathroom (left) that telegraphs dignity of the individual with its lacy decorations and its fine-furniture enclosure.

Anyone can sit on the judge’s bench in Osorio’s courtroom and view the video, or look into the glass-enclosed bathroom (left) that telegraphs dignity of the individual with its lacy decorations and its fine-furniture enclosure.

Anyone can see in Osorio’s System the cubicles where the social workers do their paper work, and how their lives are separated from their clients’. The social workers retreat to a space that the clients never see. And anyone can see how the clients are marginalized with their possessions displaced into the cage, their complex stories of lives in crisis boxed into one institutional format or another. Osorio’s installation tears down the walls that blind people involved in the system as clients, judges, social workers or administrators to one another’s humanity.

What Osorio takes, he also gives back. He may strip the judge and the social workers of their mystery, but he also restores to them humanity. And he restores to the clients their humanity. Therein lies the magic of his work.

Because Osorio is in part grappling with the irrational rules of bureaucracies and how they affect the individual in this piece, I was thinking this morning about how different his work was from that of installation artists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov.

But Osorio’s installation at the ICA stands in vivid contrast to Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s equally ambitious installations for so many reasons, yet they all are poking at the place in life where irrational bureaucracies wreak havoc.

The Kabakovs take a situation that feels unsafe and recreate it, make it more dreamlike and surreal, and therefore exaggerate the unsafety and the insanity. The bureaucracy remains an invisible power behind the daily lives of people.

The Kabakovs take a situation that feels unsafe and recreate it, make it more dreamlike and surreal, and therefore exaggerate the unsafety and the insanity. The bureaucracy remains an invisible power behind the daily lives of people.

Osorio, on the other hand, demystifies the bureaucracy and makes its spaces ordinary. He piles it high with the details of daily life, the small choices of affection and taste. The system may be insane, but the people who are part of it are doing the best they can to hold on to sanity. The flurry of personal items in the cubicles are one of the ways people hold on.

The Kabakovs’ subject is really the individual versus the government.

Osorio’s subject is the individual and the community. The government here is not so much the enemy as a victim, a community system that’s hampered by its own rules and regulations from working properly. It’s a human system.

Ultimately, Osorio is empathetic, like Forest Whitaker’s empath character in “Species.” But Osorio’s work is not only about walking in someone else’s shoes. It’s about using that connection and understanding to build community (image, Osorio at opening, listening to a boy).

Ultimately, Osorio is empathetic, like Forest Whitaker’s empath character in “Species.” But Osorio’s work is not only about walking in someone else’s shoes. It’s about using that connection and understanding to build community (image, Osorio at opening, listening to a boy).

The installation is an outgrowth of Osorio’s 3-year artist’s residency at Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services. I want to give props here to Wendy Weinberg’s video contributions to the installation.

(Top three photos, Osorio’s “Face to Face,” 2002, a predecessor of the current installation. Mixed Media including: 5 computer monitors with video, 2 large projected DVDs, TV with home video, Photo: Becket Logan, Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York)