For a good long think about how museums sanctify art and what kinds of art they sanctify, I recommend the “African Art, African Voices: Long Steps Never Broke a Back” exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

For a good long think about how museums sanctify art and what kinds of art they sanctify, I recommend the “African Art, African Voices: Long Steps Never Broke a Back” exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The show deviates somewhat from the standard vitrine and text approach, and those deviations make all the difference in enlivening–and allowing to breathe–the objects from several African cultures, their rituals and their ways of life.

The show, an adaptation of a show at the Seattle Art Museum, was drawn primarily from Seattle’s collection of several sub-Saharan cultures. Part of what makes this show so special however is it relies on advisors from each of the cultures to bring the objects to life. The advisors supply information about the objects and their contexts; some of them played a part in the selection of what got shown (image above right, Lamidi Ayankunle–in blue–with other African visitors at the press opening; Ayankunle, a Yoruban, coordinates the performances of his extended family of dancers, masqueraders, drummers and singers and is heard on the audio tour).

The show, an adaptation of a show at the Seattle Art Museum, was drawn primarily from Seattle’s collection of several sub-Saharan cultures. Part of what makes this show so special however is it relies on advisors from each of the cultures to bring the objects to life. The advisors supply information about the objects and their contexts; some of them played a part in the selection of what got shown (image above right, Lamidi Ayankunle–in blue–with other African visitors at the press opening; Ayankunle, a Yoruban, coordinates the performances of his extended family of dancers, masqueraders, drummers and singers and is heard on the audio tour).

The advisors’ words, along with their portraits and brief resumes, are posted on the wall and recorded on the show’s audioguide (which is free), thereby lending the show authority and authenticity.

The story of one of the informants or advisors provides a window into what’s special about this show. Kakuta Hamisi, a Maasai anthropology student working at the Seattle Art Museum in 1999, was dissatisfied with the museum’s Maasai objects and their documentation. So he arranged for his people to select a truly representative group of Maasai objects (jewelry shown left, its round shape representing the universe in a circular form). Hamisi documented each object by interviewing the donors and videotaping them. Those efforts–the objects, their documentation and the video are on view at the exhibit.

The story of one of the informants or advisors provides a window into what’s special about this show. Kakuta Hamisi, a Maasai anthropology student working at the Seattle Art Museum in 1999, was dissatisfied with the museum’s Maasai objects and their documentation. So he arranged for his people to select a truly representative group of Maasai objects (jewelry shown left, its round shape representing the universe in a circular form). Hamisi documented each object by interviewing the donors and videotaping them. Those efforts–the objects, their documentation and the video are on view at the exhibit.

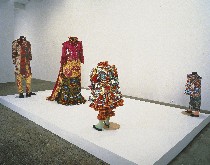

The show includes a number of other video projections. The videos alone are worth the price of admission, but in combination with the objects, they become even more meaningful and vice versa. The video of the Africans dancing, for example, enlivens the displayed masquerade costumes by showing how the costumes are used (image right: video of dancers above, some of their costumes below).,

The show includes a number of other video projections. The videos alone are worth the price of admission, but in combination with the objects, they become even more meaningful and vice versa. The video of the Africans dancing, for example, enlivens the displayed masquerade costumes by showing how the costumes are used (image right: video of dancers above, some of their costumes below).,

But finally, for me, the thing that brought this show into even stronger relief were the two rooms of contemporary African art, which is so very influenced by Western ideas that, if it weren’t so good, it would have been depressing.

The bottom line is the modern African artists — and African artists in diaspora — have taken our Western traditions of precious objects hanging on walls and transformed them, mixing them with African values and strategies and making them their own.

Of the traditional objects, I was thoroughly impressed by the Mande hunter’s shirts, leather tunics decorated with things like animal teeth, horns, shells, amulets and strip-woven cloth suggest the wearer’s power and knowledge of nature. The wearers of these shirts–loners, essentially, are larger than life, heroic and fearsome, said Pamela McCluskey, the Seattle Art Museum’s curator who organized the show in Seattle and here and who spent part of her life in Nigeria (image left, hunter’s vest, 20th century, strip-weave cloth, horns, cotton twine, leather, amulets).

Of the traditional objects, I was thoroughly impressed by the Mande hunter’s shirts, leather tunics decorated with things like animal teeth, horns, shells, amulets and strip-woven cloth suggest the wearer’s power and knowledge of nature. The wearers of these shirts–loners, essentially, are larger than life, heroic and fearsome, said Pamela McCluskey, the Seattle Art Museum’s curator who organized the show in Seattle and here and who spent part of her life in Nigeria (image left, hunter’s vest, 20th century, strip-weave cloth, horns, cotton twine, leather, amulets).

The masks look quite different from the ones that inspired Picasso because the ones in the exhibit are dressed. The austere wooden form beneath the cowrie shells and raffia are what inspired the cubist and modernist artists, but the Africans use those forms as a base on which to add caps, hair, whatever will bring the masks to life (image right, Ga Wree Wree Mask, early 20th century, Dan, Liberia, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire; wood, cloth, bells, leopard teeth, hairpins, cowry shells, and twine, 19 ¾ inches).

The masks look quite different from the ones that inspired Picasso because the ones in the exhibit are dressed. The austere wooden form beneath the cowrie shells and raffia are what inspired the cubist and modernist artists, but the Africans use those forms as a base on which to add caps, hair, whatever will bring the masks to life (image right, Ga Wree Wree Mask, early 20th century, Dan, Liberia, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire; wood, cloth, bells, leopard teeth, hairpins, cowry shells, and twine, 19 ¾ inches).

The display of objects for the most part eschews vitrines except when needed to protect small, portable objects. This unmediated view of the work is an enormous improvement over the usual museum display, because these objects are not meant to be precious, as in preserved in amber. One of the points of the exhibit is that African art is used and functional–either as part of rituals or somehow otherwise incorporated in life.

Most of the contemporary work I had never seen before.

The exceptions were from Nigerian-born Yinka Shonibare, who has work up at the Fabric Workshop right now; South African William Kentridge, whose work we drool over on a regular basis; and photographer Samuel Fosso, a Camaroonian whose work I mentioned recently in a post about the Studio Museum in Harlem. Shonibare’s “Nuclear Family” (left) at the Art Museum is more powerful than what’s at the Fab, and the museum’s audioguide gives you a chance to listen to him talking about it.

The exceptions were from Nigerian-born Yinka Shonibare, who has work up at the Fabric Workshop right now; South African William Kentridge, whose work we drool over on a regular basis; and photographer Samuel Fosso, a Camaroonian whose work I mentioned recently in a post about the Studio Museum in Harlem. Shonibare’s “Nuclear Family” (left) at the Art Museum is more powerful than what’s at the Fab, and the museum’s audioguide gives you a chance to listen to him talking about it.

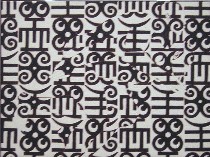

Just to mention a few of the artists who were new to me, Kwesi Owusu-Ankomah’s “Off My Back” (right) merges Western culture’s canvas with patterns inspired by traditional African decorative, mural painting techniques. The embedded figure’s painted body camouflages him–a very different attitude from Western individualism.

Just to mention a few of the artists who were new to me, Kwesi Owusu-Ankomah’s “Off My Back” (right) merges Western culture’s canvas with patterns inspired by traditional African decorative, mural painting techniques. The embedded figure’s painted body camouflages him–a very different attitude from Western individualism.

Kenyan Allen deSouza’s chromogenic prints on aluminum of set-up cityscapes have a heat-soaked exoticism. His “Everything West of Here is Indian Country” raises the issue of who gets to define what civilization is. I like this guy’s sense of humor.

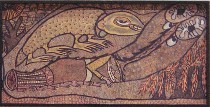

I thought I’d put up an image of Twins Seven Seven’s “Sea Ghosts 3” (left) ink on plywood, just because I liked it and I had a decent image; the artist is Nigerian.

I thought I’d put up an image of Twins Seven Seven’s “Sea Ghosts 3” (left) ink on plywood, just because I liked it and I had a decent image; the artist is Nigerian.

The photograph of the sugar cane cutter (right) by South African photographer Zwelethu Mthethwa shocked me with the subject’s personal power and made me think back to the hunter’s shirts, even though he is not a hunter.

The photograph of the sugar cane cutter (right) by South African photographer Zwelethu Mthethwa shocked me with the subject’s personal power and made me think back to the hunter’s shirts, even though he is not a hunter.

A bunch of commercial photographs from Mali by Malick Sidibe are full of wit and visual charm (left, “Untitled [Three Girls and a Baby]”).

A bunch of commercial photographs from Mali by Malick Sidibe are full of wit and visual charm (left, “Untitled [Three Girls and a Baby]”).

The contemporary art shown reflects a great variety of practice, from prints to carved wood and stone, to cast resin. It will certainly disabuse you of any notion that Africa is a sleepy backwater. And the traditional pieces will disabuse you of any notion that there’s no culture in Africa. It’s rich with cultures.

I guess I really loved this show, and I hope everyone and his brother gets a chance to see it.