So what is perfect anyway? I grew up with a father who was always looking for it, expecting it, demanding it. I never knew what it was but I lived in fear of it.

Dennis Beach‘s practically perfect in every way sculptural objects at Schmidt-Dean got me started thinking about artists seeking perfection. Libby referred to the surfer dude ambiance of Beach’s brightly-colored, surfboard-like works in her post. Indeed the beach and the waves are all over Beach’s work.

The freestanding sculptural wave (shown at top) made of glued wood and laminated into that perfect rams horn curl is a little bit of magic. Is perfection that bit of magic when something comes together and seems to defy gravity and achieve a pleasing shape?

Is there perfection in the mathematical implications of torque in Beach’s other big sculpture? (shown) This piece—patinated white concrete bars stacked (no armature) into the Fred and Ginger-like dancer—exudes a mathematical correctness and elegance that says, like all Beach’s works, that he’s a seeker of the perfect moment, perfect object, perfect work.

Maybe perfection comes in the process of working? Beach crafts his pieces beautifully. He paints them with love. The process of making them is not one of satisficing but one of seeking the perfect object.

Tom Brummett, whose new, elegant landscape photographs are paired with Beach at S-D, has sought the perfect picture through the window in his works. This is a Japanese conceit, the perfect scene through the window. Are the Japanese as a culture fueled by the search for perfection?

Brummett’s works, imbued with the hard work of the photographer’s darkroom where all the magic occurs, have an alchemical charge. They feel transformed. They may be perfect but they’re not real. they’re magic. Lots of photographers have alchemical leanings. Is the moment of transformation in the darkroom a perfect moment?

Self-Taught Perfection

Then there are works by the self-taught artists. You can see a wonderful perhaps perfect round-up of the best—Traylor, Hawkins, Castle, Pierce, Von Brunchenhein—at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in an exhibit celebrating the collection of Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz.

These works could not be less perfect in one way. But they are completely perfect in another. Often made of crude materials and imbued with a brut force of their making, these are works whose makers were not looking for perfection. (shown is Sam Doyle’s “Dr. Boles.”)

Artists like William Hawkins, who painted building portraits (like the Yaekel Building, shown left), didn’t worry about getting the building perfect. If he needed to show perspectival space, he didn’t paint it, he added on a chunk of wood or two to create 3-D illusions. (like here, look closely at the windows far left and far right).

Hawkins also used photographs in the same way to create illusions of space in works that are otherwise flat and iconic. Like some folks, Hawkins is a satisficer. When he couldn’t make it perfect himself he used something else to make it perfect. A satisfactory bit of perfection.

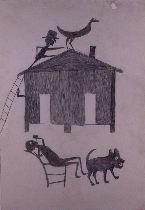

People study drawing for years and can’t achieve the perfect negative spaces of Bill Traylor (shown os “Untitled (House with Multiple Figures)). Not only does Traylor’s work pour out on the page without mistakes (is that perfection…no mistakes?) but his subject matter—people drinking, dogs fighting, folks up on the roof presumably baying at the moon—is a complete universe of human comedy, Shakespearean, without the sweat and rewrites.

Black Perfection

Quentin Morris‘s installation at PAFA pushes the artist’s 40-year long exploration of all things black into a new dimension. Morris’s decision to paint the walls of the gallery black is a perfect decision. It opens the work up on a cosmic voyager level that is delicious and inviting. This chapel of black circles on black walls is so simple in its idea it passes into the realm of perfect elegance and perfect simplicity. (shown is installation detail)

I don’t really know what perfect is. I don’t know whether it is good or bad, right or wrong. Maybe it’s in the eye of the beholder, like beauty. To my mind, a perfectly muddled and muddied drawing I’ve done can be perfect if I love it completely. And really, with each moment blending into the next and life hurtling by at astonishing speed, what’s perfect today may well be irrelevant tomorrow—or perfect tomorrow, depending on who’s looking, who’s thinking, who’s searching. Me, I’m a satisficer but I appreciate perfection when I see it. And I think about it a lot.