He was Swiss-born but nevermind. Arnold Bocklin, a painter who trained in Germany was an outsider in that country until age 50 when he began painting mythology-based works of a dark and odd nature that captivated the general art-going public but confused and dismayed the critics. Called an anti-impressionist by curator Pamela Kort, who begins her “Comic Grotesque” exhibit at Neue Gallery with a suite of the painter’s late 19th Century works, Bocklin, juxtaposed mythological and literary characters, twisted their torsos, exaggerated their scale, painted with a palette of discordant colors and made unusual compositions that were considered “too original,” according to Kort. One of Bocklin’s long-time collectors in fact, presumably influenced by the critics, returned one of the paintings to the artist. (top image, Bocklin‘s “Island of the Dead” (1880), not in the exhibit)

He was Swiss-born but nevermind. Arnold Bocklin, a painter who trained in Germany was an outsider in that country until age 50 when he began painting mythology-based works of a dark and odd nature that captivated the general art-going public but confused and dismayed the critics. Called an anti-impressionist by curator Pamela Kort, who begins her “Comic Grotesque” exhibit at Neue Gallery with a suite of the painter’s late 19th Century works, Bocklin, juxtaposed mythological and literary characters, twisted their torsos, exaggerated their scale, painted with a palette of discordant colors and made unusual compositions that were considered “too original,” according to Kort. One of Bocklin’s long-time collectors in fact, presumably influenced by the critics, returned one of the paintings to the artist. (top image, Bocklin‘s “Island of the Dead” (1880), not in the exhibit)

According to Kort, many things written about Bocklin’s paintings referred to their nature as “baroque, bizarre and burlesque,” damning adjectives at that time. Humor was a problem, too, mentioned in the same breath with thoughts about the decline of art. Tsk. tsk. (image is Max Klinger’s “Pissing Death” (@1880))

Anyway, Kort’s exhibit takes off from Bocklin and rounds up a large number of works (some 70 paintings, prints, archival film footage, sculpture, collage and documents) to demonstrate a stream of German comic subversion she sees flowing from Bocklin’s aesthetic. Early Emil Nolde and Paul Klee (yes, this was a revelation!) show those masters in a broader Bocklin context that’s most interesting. Klee’s several small etchings of deformed figures like the human/bird hybrid called “The hero with the wing” (1905) and a later more typical Klee that was called “Classical Grotesque” (1923) are high points of the exhibit.

Later practitioners like Thomas Theodor Heine up to the Dadaists and Surrealists are shown to be in sync with the comic, absurdist sensibility of Bocklin’s grotesques. Here are a few highlights from a show I highly recommend, especially if you carry with you thoughts about what’s going on in the world and in the world of art today when grotesque art, far from pooh pooh’d is being brought in to the mainstream. (Remember Robert Storr‘s 2004 Biennial, Site Santa Fe which focussed exclusively on the subject. And here, as an aside, I’ll remind you that Storr and Kort, who are seemingly on the same wavelengh, co-curated the wonderful Jorg Immendorff exhibit at Moore College in 2004. See Immendorff in our artist’s list for more on that.) We’re at a time now when moral tsk-tsking seems to be out the window and all is fair in love and art. That’s not a bad thing, I just mention it for context.

Notable works

Heine, represented by a series of works featuring the devil, called Simplicissimus, have a cultish “Night on Bald Mountain” appeal. His small, bronze statue of the devil– whose Simpsons-like head and hair provides a new interpretation for that cast of characters! — is just plain great. (shown, above left) A kind of anti-Lipschitz work, it’s oddness is endearing.

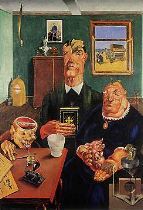

Several works by George Grosz, like “Christ with a gas mask” (1927) bring politics in (it seems to be there under the skin of many of the works). Raul Hausmann’s collages, Hannah Hoch‘s really great collages (she makes it look so easy) and Georg Scholz’s “Industrial Farmers” (1920) are ones to linger over. (image is Hoch‘s “The eternal folk dancers” (1933))

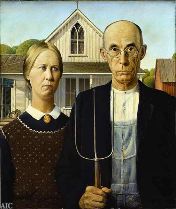

Georg Scholz‘s farmers are “American Gothic” meets “Animal Farm” and I wouldn’t want to meet any of them in a dark field, full moon or not. (right is Scholz‘s “Industry Farmers” (1920) and left below is Grant Wood‘s “American Gothic” (1930))

Kort includes the cabaret burlesque as a kind of pop culture approximation of grotesque. Her inclusion of performance artist Karl Valentin’s silent films — there’s a selection of shorts running in a curtained-off room with some benches for seating — gives a “you are there” moment to the show. The works flow quickly and are moving pictures as odd and dark as many of the paintings and prints.

The Museum

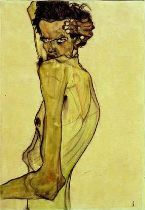

The MuseumJust a word about the Neue Gallery itself. Opened in 2001, the museum, on 86th and 5th, which used to be Mrs. Vanderbilt’s abode, has an intimate atmosphere that complements the permanent collection of German and Austrian art by Gustav Klimt, Max Beckmann, Adolf Loos, Egon Schiele and others. My sister, Cate, who visited the museum with me and who is a long-time New York resident, wondered about how a museum devoted to German art could survive in the big town, but when we were there, on a Sunday afternoon in January, it was crowded. (right is Schiele‘s “Self Portrait with arm twisted above head” (1910) which had the same energy as Pontormo’s twisted torso self portrait in the current PMA exhibit focussed on the Renaissance master)

The museum’s location up the street from the Met has to serve it well and in fact I read recently that Neue catches some of the Met’s spillover crowds. (something Barnes will be privy to when it moves near to the PMA).

The collection’s got some great Klimt paintings, a room of Schiele and Alfred Kubin drawings, the latter, new to me, a German Goya making fantastical brooding figures.

Outsiders and a final thought

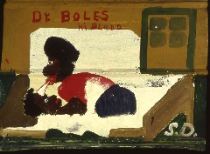

Art by self-taught artists fits the grotesque category and belongs in the discussion. The popularity of these artists today at a time when grotesque in general is not only accepted but lauded should be no surprise. (left is Sam Doyle‘s “Dr. Boles” on view at the Rosenbach Museum in the “Passionate Eye” exhibit.)

Kort’s exhibit spans the years 1870-1940. Not only does that time frame bridge two centuries but it includes two world wars. While she doesn’t, I beleive, discuss it per se, I have to think that those three major events (century-turning, World War 1 and World War 2) did much to propel artists’ and audience’s thoughts toward the darker recesses of their brains where pessimism and fear play. In that respect, our times –which include not only century-turning but millenium-turning; two wars in Iraq; several wars in Afghanistan; the seemingly unstoppable rise of terrorism; and eco-disasters of human making (Exxon Valdez and its spawn) ally the art of our times with the art of Bocklin and his children.