Just thought I’d add one more thought about Eamon Ore-Giron’s excellent one-man show, “Mirage,” at the Morris Gallery at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (for more, see Roberta’s story at the Philadelphia Weekly here, and my post on the artist’s talk).

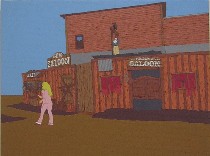

Just thought I’d add one more thought about Eamon Ore-Giron’s excellent one-man show, “Mirage,” at the Morris Gallery at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (for more, see Roberta’s story at the Philadelphia Weekly here, and my post on the artist’s talk).The land is flat–a stripe of land. When he uses two or three stripes of land, they indicate depth and distance. There, the shift of receding colors is not gradual but expressed in flat stripes. On top is a stripe of sky above. For the most part, perspective is not an element.

The bodies are also flat. Most have no modeling to show roundness. They rely on line and shape for their depth. Because of this approach, which is straight out of graphic design and children’s storybook illustrations, Ore is signalling that he’s telling a story and that it’s not necessarily a representation of visual reality. The paintings read almost as silkscreens or collages.

The bodies are also flat. Most have no modeling to show roundness. They rely on line and shape for their depth. Because of this approach, which is straight out of graphic design and children’s storybook illustrations, Ore is signalling that he’s telling a story and that it’s not necessarily a representation of visual reality. The paintings read almost as silkscreens or collages.

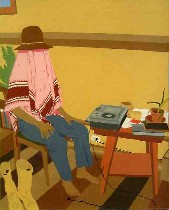

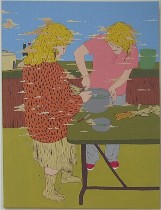

The only 3-D element in many of the paintings is shadows, which in that flattened context take on significance. The pink-clad tourist in “Brown Town” (image top of post) is nearly shadowless compared to the faux Wild West; the myth has become a solid reality to us. In “Praise for the Morning” (right) the body, chair and table do not cast shadows. Only the hat does. In “Cookin’ 1” (left) the people cast no shadows at all.

The only 3-D element in many of the paintings is shadows, which in that flattened context take on significance. The pink-clad tourist in “Brown Town” (image top of post) is nearly shadowless compared to the faux Wild West; the myth has become a solid reality to us. In “Praise for the Morning” (right) the body, chair and table do not cast shadows. Only the hat does. In “Cookin’ 1” (left) the people cast no shadows at all.

What makes “…Morning” and “Cookin’ 1” have power is their snapshot ordinariness transmogrified into significance. In “Cookin’ 1,” it’s a ritual and a memory. In “Praise…,” it’s the magic of identity disguised by the objects and clothes.

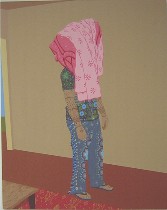

Ore-Giron’s predicament is much like our own, only more so. Is the girl with pink hair really a pink-haired girl? Is the boy with the eyebrow piercing really that person? A person’s essence and background, measured through the filters of culture and costume, is never visible at a glance. Identity is too complex for the symbols we assign (right, “Exit Strategy,” with the painter dressed in over-the-top cowboy pants styled after Native American garb, a shirt styled after Huichol (Mexican) peyote-vision patterns and mendhi arm decorations, enough identities for any one human to support).

Ore-Giron’s predicament is much like our own, only more so. Is the girl with pink hair really a pink-haired girl? Is the boy with the eyebrow piercing really that person? A person’s essence and background, measured through the filters of culture and costume, is never visible at a glance. Identity is too complex for the symbols we assign (right, “Exit Strategy,” with the painter dressed in over-the-top cowboy pants styled after Native American garb, a shirt styled after Huichol (Mexican) peyote-vision patterns and mendhi arm decorations, enough identities for any one human to support).

What makes this work so resonant is partially this–the story of Ore-Giron’s mixed identity is a metaphor for the identity of each of us. But it’s also resonant because of the story the paintings tell. They take a hard look at the stories we tell as a culture–the myths we have invented and then come to believe about the past and the present.